Economists might be finally closing in on the reason for asset bubbles. How to pop them before they grow too large, however, is a much harder problem.

The study of bubbles has steadily gathered urgency during the past four decades as crashes became more spectacular and more damaging.

The stock crash of 1987 was a wake-up call for those who had assumed that markets function efficiently; there was no obvious reason why rational investors would suddenly conclude that US companies were worth 23 percent less than the day before.

Photo: AFP

The tech bubble was even more troubling, because many observers had warned of a bubble for years before the crash, to no avail.

The same thing happened with the housing bubble, only when that one burst it took the real economy with it — as tends to happen when rapid asset-price declines are combined with high levels of debt.

Researchers have developed a large and diverse array of theories about why asset prices suddenly rise and crash. The difficulty in identifying the cause of bubbles has made it hard to design policies to prevent them.

However, recently, a growing number of economists are zeroing in on the idea of what they call extrapolative expectations.

For whatever reason, it seems, investors sometimes decide that a recent run of good returns represents some sort of deep structural trend.

A new paper by Zhenyu Gao (高振宇), Michael Sockin and Wei Xiong (熊偉) supports this idea. Looking at housing prices during the bubble, they compared US states based on how much they changed their capital gains tax rates. The states that raised taxes more saw less of a bubble and crash.

However, even more tellingly, the authors found that in states with lower capital gains taxes, purchases of investment properties that the owners did not plan to live in tend to increase more in response to recent price gains.

The simplest explanation for this pattern is that when prices go up and there are not tax hikes to make people expect a reversal, they start to think that the trend will continue for the foreseeable future, and they buy accordingly.

A recent study by researchers at the Bank of Canada provided different evidence that pointed in the same direction.

In surveys, they found, most people expect that house prices will rise and fall during a five-year period.

However, when the researchers show people data on recent prices, they start to believe that current trends will continue for the next five years.

Other papers found the same pattern. Economists Theresa Kuchler and Basit Zafar found that in areas where local housing prices increased more, people tend to expect that prices will go up more nationwide in the years to come.

Obviously, investors do not always expect recent trends to continue forever. So what makes them start to extrapolate? It might be that when a price trend gets big enough for people to notice, human psychology tends to assume that this is the new normal.

If house prices in your neighborhood normally go up and down, but then they suddenly start going up by big amounts each year for several years, you might assume that the game has simply changed. In that case, the obvious thing to do is to buy, buy, buy.

Defenders of the idea of efficient markets might retort that if this happens, savvier investors — who think carefully about whether a price trend is justified by underlying fundamentals — would simply bet against the trend-followers and bring things back into line.

However, economic theorists have long understood that because rational investors have limited firepower to short a bubble, they often find it more worthwhile to ride the rising prices for a while. That just makes the bubble worse.

So economists are starting to get a picture of why bubbles happen. Some event — maybe an increased supply of credit to home buyers — increases demand for houses or stocks and pushes up prices for a few years. Speculators see that and decide that prices just go up now, so they buy in, increasing prices even more.

Rational investors know there is a bubble, but decide to buy in for a while and try to sell at the top. The crash only happens when speculators run out of money to keep buying.

If this unified theory of bubbles turns out to be right, the next question becomes: How can governments nip the process in the bud?

Gao and his colleagues suggest that tax hikes could be an answer. If economists can figure out how many years of rising prices — say, three or five — is needed to create the impression of a permanent trend in speculators’ minds, then policymakers could adopt a rule where capital gains taxes temporarily go up whenever prices rise for that many years in a row.

This policy has very little downside. If there is a sound fundamental reason prices are rising — for example, a surge in demand for housing — then the higher capital gains taxes would skim off some of the windfall.

If it really is the start of a bubble, the sudden tax increase would damp speculators’ expectation for eternally rising prices.

If this kind of automated tax system prevents bubbles from getting out of hand, it would be a huge victory for behavioral finance — and for everyone who would no longer have to fear the whims of out-of-control asset markets.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University. He blogs at Noahpinion.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

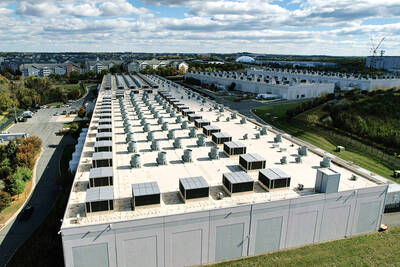

The demise of the coal industry left the US’ Appalachian region in tatters, with lost jobs, spoiled water and countless kilometers of abandoned underground mines. Now entrepreneurs are eyeing the rural region with ambitious visions to rebuild its economy by converting old mines into solar power systems and data centers that could help fuel the increasing power demands of the artificial intelligence (AI) boom. One such project is underway by a non-profit team calling itself Energy DELTA (Discovery, Education, Learning and Technology Accelerator) Lab, which is looking to develop energy sources on about 26,305 hectares of old coal land in

Taiwan’s exports soared 56 percent year-on-year to an all-time high of US$64.05 billion last month, propelled by surging global demand for artificial intelligence (AI), high-performance computing and cloud service infrastructure, the Ministry of Finance said yesterday. Department of Statistics Director-General Beatrice Tsai (蔡美娜) called the figure an unexpected upside surprise, citing a wave of technology orders from overseas customers alongside the usual year-end shopping season for technology products. Growth is likely to remain strong this month, she said, projecting a 40 percent to 45 percent expansion on an annual basis. The outperformance could prompt the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and

Netflix on Friday faced fierce criticism over its blockbuster deal to acquire Warner Bros Discovery. The streaming giant is already viewed as a pariah in some Hollywood circles, largely due to its reluctance to release content in theaters and its disruption of traditional industry practices. As Netflix emerged as the likely winning bidder for Warner Bros — the studio behind Casablanca, the Harry Potter movies and Friends — Hollywood’s elite launched an aggressive campaign against the acquisition. Titanic director James Cameron called the buyout a “disaster,” while a group of prominent producers are lobbying US Congress to oppose the deal,

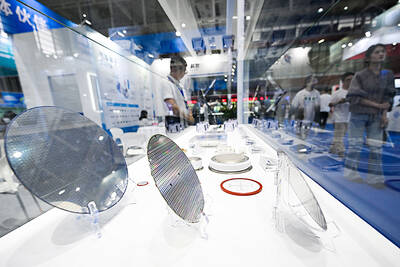

Two Chinese chipmakers are attracting strong retail investor demand, buoyed by industry peer Moore Threads Technology Co’s (摩爾線程) stellar debut. The retail portion of MetaX Integrated Circuits (Shanghai) Co’s (上海沐曦) upcoming initial public offering (IPO) was 2,986 times oversubscribed on Friday, according to a filing. Meanwhile, Beijing Onmicro Electronics Co (北京昂瑞微), which makes radio frequency chips, was 2,899 times oversubscribed on Friday, its filing showed. The bids coincided with Moore Threads’ trading debut, which surged 425 percent on Friday after raising 8 billion yuan (US$1.13 billion) on bets that the company could emerge as a viable local competitor to Nvidia