A century after mass protests against Japanese colonial rule on the Koream Peninsula, the issue of those who collaborated with Tokyo — many of whom later become part of the South Korean elite — remains hidden.

When the Seoul government signed a 1910 treaty handing sovereignty over the peninsula to Japan, their new overlords awarded 76 key politicians and officials Japanese noble titles and pensions.

Over the next 35 years, hundreds of thousands of Koreans worked for colonial authorities as civil servants, soldiers, teachers or police.

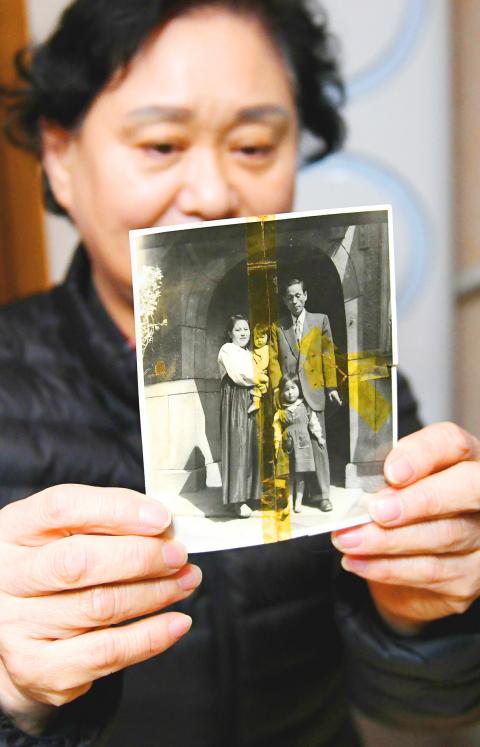

Photo: AFP

According to historians, hundreds of thousands more were forcibly recruited as frontline troops, slave workers and wartime sex slaves.

A few thousand others went into exile in China to fight Japanese forces.

The independence struggle is at the heart of Korean national identity in North and South Korea, but eight in 10 South Koreans believe their country has never properly come to terms with the issue of collaboration, according to a government study released for last week’s 100th anniversary of the March 1 Independence Movement.

Mass protests against Japanese rule began that day in 1919, only to be forcibly put down, with 7,500 people killed within two months and 46,000 arrested, according to Seoul’s national archives.

In a commemorative speech, South Korean President Moon Jae-in said: “Wiping out the vestiges of pro-Japanese collaborators” was a “long-overdue undertaking.”

However, it is an intensely political issue, with collaborators generally seen as right-wing and Moon under pressure from conservatives looking to paint him as a Northern sympathizer.

The US atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, forced Tokyo’s World War II surrender and ended colonial rule only for the victors to divide the peninsula.

Then-North Korean leader Kim Il-sung’s Moscow-backed regime executed Japanese collaborators en masse.

In the South, the US-oriented administration of then-South Korean president Syngman Rhee recruited many colonial-era officers and officials into its ranks to exploit their expertise and experience.

“Even in the liberated homeland, those who used to serve as police officers during Japanese colonial rule painted independence activists as Reds [communists] and tortured them,” Moon said.

Historical resentment sours relations with Tokyo to this day and prevents South Korea making a proper reckoning with its past, says Lee Young-hun, a former professor of economics at Seoul National University.

“Those who are labeled as Japanese collaborators are Koreans who actively embraced modernism,” Lee said.

Among those who went into exile was Shin Young-shin’s great-grandfather, a Korean general imprisoned and tortured by Japanese-backed troops. Both of her parents took part in the campaign, but struggled to feed their family when they returned to the South in the late 1940s.

“My parents got nothing — not even a penny from the government — for their activism while they were alive,” Shin, 71, told reporters in her small basement flat in Ansan, south of Seoul.

According to local government data almost three-quarters of independence activists’ descendants in Seoul make less than 2 million won (US$1,800) a month.

However, many descendants of collaborators — defined by South Korean law as those who received titles under Japanese rule, or arrested or killed independence fighters — have prospered.

One of those ennobled in 1910, and included on a list of 1,005 collaborators Seoul issued 10 years ago, was Song Byung-jun.

His son led the forces that jailed Shin’s great-grandfather, and his grandson became the first director of Seoul’s central bank.

Some of the South’s biggest conglomerates were founded during the colonial period. High-profile executives, including Hyundai Group’s chairwoman Hyun Jeong-eun, have sued to remove ancestors’ names from the list of collaborators.

Former South Korean president Park Chung-hee was an officer in the Japanese forces before ruling the South as a military-backed dictator for 18 years until his 1979 assassination. His daughter was elected president in 2012.

Park was not officially classed as a collaborator, but is on a longer list of 4,389 names collated by the Center for Historical Truth and Justice campaign group, which includes prominent cultural figures such as Ahn Eak-tai, composer of the South Korean national anthem.

“There is a popular Korean saying that translates to: ‘Those who fought for independence have made three generations of their descendants suffer. Those who collaborated with the Japanese have made three generations of their descendents prosper,’” center researcher Lee Yong-chang said.

Shin — whose mother was posthumously awarded the South Korean Order of Merit for National Foundation — will never come to terms with the contrast.

“I have prayed so that I could love my enemies, but I cannot possibly love the Japanese collaborators,” she said.

Australia has announced an agreement with the tiny Pacific nation Nauru enabling it to send hundreds of immigrants to the barren island. The deal affects more than 220 immigrants in Australia, including some convicted of serious crimes. Australian Minister of Home Affairs Tony Burke signed the memorandum of understanding on a visit to Nauru, the government said in a statement on Friday. “It contains undertakings for the proper treatment and long-term residence of people who have no legal right to stay in Australia, to be received in Nauru,” it said. “Australia will provide funding to underpin this arrangement and support Nauru’s long-term economic

‘NEO-NAZIS’: A minister described the rally as ‘spreading hate’ and ‘dividing our communities,’ adding that it had been organized and promoted by far-right groups Thousands of Australians joined anti-immigration rallies across the country yesterday that the center-left government condemned, saying they sought to spread hate and were linked to neo-Nazis. “March for Australia” rallies against immigration were held in Sydney, and other state capitals and regional centers, according to the group’s Web site. “Mass migration has torn at the bonds that held our communities together,” the Web site said. The group posted on X on Saturday that the rallies aimed to do “what the mainstream politicians never have the courage to do: demand an end to mass immigration.” The group also said it was concerned about culture,

ANGER: Unrest worsened after a taxi driver was killed by a police vehicle on Thursday, as protesters set alight government buildings across the nation Protests worsened overnight across major cities of Indonesia, far beyond the capital, Jakarta, as demonstrators defied Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto’s call for calm. The most serious unrest was seen in the eastern city of Makassar, while protests also unfolded in Bandung, Surabaya, Solo and Yogyakarta. By yesterday morning, crowds had dispersed in Jakarta. Troops patrolled the streets with tactical vehicles and helped civilians clear trash, although smoke was still rising in various protest sites. Three people died and five were injured in Makassar when protesters set fire to the regional parliament building during a plenary session on Friday evening, according to

STILL AFLOAT: Satellite images show that a Chinese ship damaged in a collision earlier this month was under repair on Hainan, but Beijing has not commented on the incident Australia, Canada and the Philippines on Wednesday deployed three warships and aircraft for drills against simulated aerial threats off a disputed South China Sea shoal where Chinese forces have used risky maneuvers to try to drive away Manila’s aircraft and ships. The Philippine military said the naval drills east of Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan Island, 黃岩島) were concluded safely, and it did not mention any encounter with China’s coast guard, navy or suspected militia ships, which have been closely guarding the uninhabited fishing atoll off northwestern Philippines for years. Chinese officials did not immediately issue any comment on the naval drills, but they