Nestled in the mountain region of northern Taiwan lies a small village that was once bustling due to a thriving coal industry, only to later gain fame for an entirely different reason — cats. This is Houtong Cat Village (猴硐貓村), located in Ruifang District, New Taipei City.

Traditional Coal Mining and Village Transformation

Houtong was originally known as “Monkey Cave” (houtong, 猴洞), a name derived from the wild monkeys that once inhabited caves in the surrounding hills. During the Japanese colonial period in the early 20th century, rich coal deposits were discovered and developed, rapidly turning Houtong into one of northern Taiwan’s most important coal-producing areas.

Photo: New Taipei City Government Animal Protection and Health Inspection Office 照片:新北市動保處提供

However, between the 1970s and 1990s, as oil and other energy sources rose to prominence, the coal industry gradually declined. Young residents left for cities in search of work, leaving behind only a small elderly population and a village slowly falling into decay.

Houtong’s Turning Point: Stray Cats and Community Power

After entering the 2000s, a combination of vacant houses and feeding by a handful of residents led to the gradual gathering of stray cats in the village. In 2008, a cat enthusiast began organizing volunteers to care for these cats and shared their stories and photographs online, unexpectedly attracting widespread attention. This grassroots enthusiasm drew more volunteers and gradually shaped the distinctive landscape of what would become known as a “cat village.”

Photo courtesy of Zhou Chao-nan, Houtong Miner’s Heritage Museum 照片:猴硐礦工文史館周朝南提供

While the departure of human residents had plunged the village into decline, the growing cat population began attracting visitors. Cafes, souvenir shops and cat-themed merchandise emerged, revitalizing Houtong in an entirely new way.

At its peak, Houtong was home to more than 200 cats. In 2013, CNN even named it one of the top six “Travel hotspots where cats rule,” drawing large numbers of domestic and international visitors.

Yet between 2025 and 2026, even as the village remained beloved by tourists, it faced a sobering reality: the number of street cats had plummeted. From an estimated 200–300 cats at its height, reports and local observations suggest that fewer than 30 remain today.

Photo: New Taipei City Government Animal Protection and Health Inspection Office 照片:新北市動保處提供

When Successful TNR Is Treated as Failure

Houtong Cat Village is losing its most recognizable symbol. As the number of cats declines, so too does tourist traffic. Viewed globally, most places famous for cats eventually reach the same crossroads: when animal welfare is genuinely implemented, tourism logic begins to unravel.

Japan’s Aoshima Island offers the most emblematic example. Once famous for having “more cats than people,” the island saw its cat population naturally decline after the comprehensive implementation of TNR (Trap–Neuter–Return). Elderly cats passed away, no new kittens were born, and the tourism boom quickly faded. The Japanese government even issued a public statement: “This is not a tourist destination. Please do not come here just to see cats.”

From an animal welfare perspective, this represents a textbook success. Yet in tourism discourse, it is often labeled as “decline.” Houtong is now retracing this same path. The reduction in cat numbers does not indicate management failure; rather, it reflects the effectiveness of sterilization, medical care, and long-term management.

Istanbul, by contrast, offers a different vision. The city has no designated “cat village,” yet it is widely regarded as one of the most cat-friendly cities in the world. The key lies not in numbers, but in positioning. Cats are not treated as tourist attractions on display, but as urban residents. The municipal government provides vaccinations, sterilization programs and public cat shelters; residents voluntarily care for the animals, while visitors remain observers rather than consumers.

When Animal Welfare and Tourism Logic Collide

Experiences around the world repeatedly demonstrate a fundamental tension: animal welfare prioritizes stability, health and minimal disturbance, while tourism seeks density, predictability and high visibility. These goals are inherently at odds.

Rome’s archaeological cat sanctuaries have chosen to side decisively with the animals. Cats are officially recognized as part of the city’s cultural heritage, but human interaction is strictly regulated. Photography and feeding are governed by clear rules, allowing the cats to exist quietly and sustainably. Tourism may lose some of its “cuteness factor,” but gains something more enduring — respect.

As Houtong confronts its shrinking cat population, the crucial question is not merely how to respond, but how to rethink its priorities: Should the goal be to “restore the number of cats,” or to accept a future in which cats are no longer the main attraction?

(Lin Lee-kai, Taipei Times)

在台灣北部的山城裡,有個曾因煤礦業興盛而熱鬧的小村落,後來卻因貓咪聲名遠播——這就是新北市瑞芳區的猴硐貓村。

傳統煤礦與村落轉型

猴硐最早的名字叫做「猴洞」,原是因為山中有野猴出沒的洞穴而得此稱。後來在日本殖民時期(約20世紀初),村內開發出豐富的煤礦資源,使這裡迅速變成台灣北部重要的煤炭產地之一。

然而到了1970~1990年代,隨著石油與其他能源的興起,猴硐的煤礦業逐步衰退,許多年輕人西遷求職,留下的只有一些老人與逐漸凋零的聚落。

猴硐的轉機:流浪貓與社群力量

進入2000年代後,由於村落閒置空屋以及少數人的餵養,村裡開始聚集一群流浪貓。2008年,一位貓咪愛好者開始串連志工、照護這些貓,並透過網路分享照片和故事,意外引起大量關注。於是吸引了更多志工前來照料貓咪,也逐漸形成了這「貓村」的獨特風景。

原本人類的消失讓村莊陷入蕭條,但貓咪的增加卻吸引了遊客,帶動了咖啡廳、紀念品店、貓主題商品等旅遊產業興起,讓猴硐以不同的方式重獲活力。

貓咪數量的巔峰時期曾有超過200隻,2013年還被CNN評選為「全球六大賞貓景點」,吸引大批國內外遊客朝聖看貓。

然而,到了2025~2026年間,猴硐貓村在被遊客熱愛的同時,也面臨一個沉重的現實:街頭貓咪數量大幅下降。曾經約200~300隻的貓咪,據報導和在地觀察,如今只剩下約不到30隻。

成功的TNR,為何被當成失敗?

猴硐貓村正在失去它最醒目的標誌。貓變少了,遊客也跟著減少。放眼世界,多數以貓聞名的地方,最後都會走到同一個十字路口:當動物福利被落實,觀光邏輯反而開始崩解。

日本青島是最典型的例子。這座曾因「貓比人多」而爆紅的小島,在全面實施TNR(捕捉、結紮、回放)後,貓咪數量自然下降。老貓離世,幼貓不再出生,觀光熱潮迅速退去。日本政府甚至公開聲明:「這裡不是觀光景點,請不要為了看貓而來」。

從動物福利的角度看,這是一個教科書式的成功案例;但在觀光話語裡,卻被標記為「沒落」。猴硐正重演這條路線。貓隻減少,並非管理失靈,而恰恰是結紮、醫療與照護發揮效果的結果。

伊斯坦堡則提供了另一種想像。這座城市並沒有「貓村」,卻被譽為世界上最愛貓的城市之一。其關鍵不在數量,而在定位。貓不是被展示的景點,而是被視為城市居民。市政府提供疫苗、結紮、公共貓屋,居民自發照顧,遊客只是旁觀者。

當動物福利與觀光邏輯正面對撞

世界各地的經驗反覆證明:動物福利的目標是穩定、健康、低干擾;觀光的目標是密集、可預期、高可見度。這兩者天生緊張。

羅馬的貓考古遺址選擇站在動物那一邊。貓被正式視為文化資產的一部分,但互動被嚴格限制;拍照、餵食都有規範,貓的存在是低調而長久的。觀光因此少了「萌點」,卻多了尊重。

猴硐所面臨的貓數量減少,我們應該反思:究竟是要「恢復貓咪的數量」,還是「接受貓不再是主角」?

(台北時報林俐凱)

A: Wow, US climber Alex Honnold has announced that he’s going to free-climb Taipei 101 on Jan. 24. And the challenge, titled “Skyscraper Live,” will be broadcast worldwide live on Netflix at 9am. B: Oh my goodness, Taipei 101 is the world’s tallest green building. Is he crazy? A: Honnold is actually the climber in the 2019 film “Free Solo” that won an Oscar for best documentary, and was directed by Taiwanese-American Jimmy Chin and his wife. He’s a legendary climber. B: Didn’t Alain Robert, “the French Spiderman,” also attempt to scale Taipei 101 in 2004? A: Yes, but

A: There are always adventurers who want to conquer Taipei 101 as a world-class landmark. Didn’t someone once parachute from the top of it? B: Yeah, that’s right. Austrian extreme sportsman Felix Baumgartner once parachuted from the rooftop observation deck in 2007 without permission. He died earlier last year in a powered paragliding crash at the age of 56. A: Hollywood superstar Tom Cruise also almost jumped off Taipei 101 for “Mission Impossible 3.” B: What? But I didn’t see the building in the movie. A: The news says that the film’s producers applied to the Taipei City

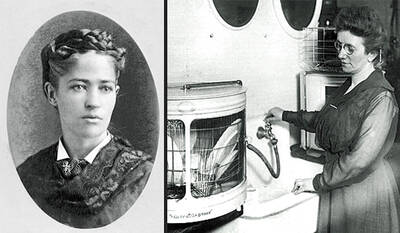

Twelve dinner guests have just left your house, and now a tower of greasy plates stares back at you mockingly. Your hands are already wrinkling as you think about scrubbing each dish by hand. This nightmare bothered households for centuries until inventors in the 19th century tried to solve the problem. The first mechanical dishwashers, created in the 1850s, were wooden machines with hand cranks that splashed water over dishes. Unfortunately, these early devices were unreliable and often damaged delicate items. The real breakthrough came in the 1880s thanks to Josephine Cochrane, a wealthy American socialite. According to her own account,

People use far more than just spoken language to communicate. Apart from using our voices to pronounce words, we also use body language, which includes countless facial expressions. Most people know that smiles and frowns indicate pleasure and displeasure, or that wide eyes with raised eyebrows typically show surprise. However, there is a lot more to learn about how facial expressions can help or hinder communication. People often unintentionally reveal their emotions through very tiny facial movements known as “microexpressions.” The term was popularized by psychologist Paul Ekman, who found that people from cultures across the world generally recognize