In most cities, food waste is often regarded as one of the most troublesome types of waste: it has a high moisture content, spoils easily and produces strong odors. If not handled properly, it can cause serious sanitation and environmental problems. From the perspective of the circular economy, however, food waste is not “useless leftovers,” but rather an organic resource that has yet to be effectively utilized.

The core principle of the circular economy is to break away from the linear model of “production–consumption–disposal,” allowing resources to circulate repeatedly within a system and extending their useful life. Food waste occupies a critical position in this cycle. Food travels from farm to the dining table, and if it ends up directly in incinerators or landfills, valuable nutrients are wasted and the environmental burden increases. With proper sorting and treatment, however, the organic matter, energy and nutrients contained in food waste can be returned to the production system.

There are several pathways for the circular use of food waste. The most common is composting, in which microorganisms decompose fruit peel and vegetable scraps into organic fertilizer that can be returned to farmland to improve soil quality. Another approach is anaerobic digestion, which converts food waste into biogas for electricity generation or heating. A third method is bioconversion, using animals or insects to transform food waste into protein and fats that can serve as feed or industrial raw materials.

Photo: CNA 照片:中央社

Feeding food waste to pigs was an early form of circular economy practice. It transformed discarded leftovers into animal protein, reduced waste, lowered feed costs and created a nearly closed-loop resource cycle. After food-waste feeding was banned due to disease prevention concerns, the black soldier fly emerged as a popular alternative treatment pathway.

The black soldier fly, a member of the Stratiomyidae family in the order Diptera, is a saprophagous insect. During its larval stage, it feeds mainly on organic matter such as food waste, animal manure and plant and animal remains. In recent years, driven by growing global demand for insect protein, the black soldier fly has become one of the 13 insect species mass-produced worldwide.

The principle behind using black soldier flies to treat food waste lies in the larvae’s highly omnivorous diet and rapid feeding rate, which allow them to convert organic matter in food waste into the protein and fat needed for their own growth. Within a short period, the larvae can consume large amounts of leftover food, vegetable scraps and some animal-based residues, significantly reducing the volume and weight of food waste. The indigestible residues can then be used as compost or soil conditioners, forming a bioconversion cycle.

Photo: Chen Kuan-pei, Liberty Times 照片:自由時報記者陳冠備

The advantages of this approach include high processing efficiency, effective waste reduction, relatively low land and time requirements and the production of larvae with high protein value that can be used as feed, achieving both waste reduction and resource recovery. In addition, adult black soldier flies do not feed or bite humans, and compared with traditional food waste treatment methods, they pose lower risks of disease vectors and odor.

Nevertheless, there are also drawbacks. The system is sensitive to temperature and humidity and requires careful management to operate stably. Food waste still needs basic sorting and pretreatment to avoid excessive salinity or contamination. Moreover, challenges remain in terms of regulations, food safety, and social acceptance. As a result, black soldier fly treatment is currently better suited to small-and medium-scale or pilot applications, and it has yet to fully replace existing food waste management systems.

(Lin Lee-kai, Taipei Times)

Photo: Chen Kuan-pei, Liberty Times 照片:自由時報記者陳冠備

在多數城市裡,廚餘往往被視為最麻煩的垃圾之一:含水量高、容易腐敗、氣味明顯,處理不當便會帶來衛生與環境問題。然而,從循環經濟的角度來看,廚餘並不是「無用的剩餘物」,而是一種尚未被妥善利用的有機資源。

循環經濟的核心精神,在於打破「生產—消費—丟棄」的線性模式,讓資源在系統中反覆流動、延長使用價值。廚餘正好位於這條循環鏈的關鍵位置。食物從農田進入餐桌,最後若直接進入焚化爐或掩埋場,不僅浪費了其中的養分,也增加了環境負擔;但若能妥善分類與處理,廚餘中的有機質、能量與養分,仍有機會回到生產體系之中。

廚餘的循環利用有多種途徑。最常見的是堆肥化,透過微生物分解,將果皮、菜葉等轉為有機肥料,回到農地改善土壤。

Photo: Screen grab from Hsinchu County Government’s Web site 照片:取自新竹縣政府官網

其次為厭氧消化,將廚餘轉為沼氣,用於發電或供熱。

另一種是生物轉換,利用動物或昆蟲將廚餘轉化為蛋白質與脂肪,作為飼料或工業原料。

廚餘養豬是「循環經濟」的早期實踐。它將原本要被丟棄的剩食,轉化為動物蛋白,減少廢棄物,同時降低飼料成本,形成一個近乎封閉的資源循環。

基於防疫考量而禁用廚餘養豬後,黑水虻成為熱門的去化管道。

黑水虻為雙翅目水虻科,屬於腐食性昆蟲,幼蟲階段多以廚餘、動物糞便、動植物屍體等有機物為食。近年來,全球因昆蟲蛋白需求增加,黑水虻已是全世界量產的13種昆蟲之一。

黑水虻處理廚餘的原理,是利用其幼蟲高度雜食且取食速度快的特性,將廚餘中的有機質轉化為自身生長所需的蛋白質與脂肪。幼蟲可在短時間內大量攝食剩飯、菜葉與部分動植物性殘渣,使廚餘體積與重量顯著減少,而無法消化的殘渣則可作為堆肥或土壤改良材料,形成生物轉換的循環過程。

其優點在於處理效率高、減量效果佳,占地與時間需求相對低,且產出的幼蟲具有高蛋白價值,可作為飼料原料,兼具廢棄物減量與資源再利用的功能。此外,黑水虻成蟲不取食、不叮人,相較傳統廚餘處理方式,病媒與異味問題較低。

然而,其缺點也相當明顯,包括對溫度與濕度條件敏感,需良好管理才能穩定運作;廚餘仍需基本分類與前處理,避免過鹹或受污染;同時在法規、食安與社會接受度上仍有挑戰,因此較適合中小規模或示範型應用,尚難全面取代既有廚餘處理體系。

(台北時報林俐凱)

A: Wow, US climber Alex Honnold has announced that he’s going to free-climb Taipei 101 on Jan. 24. And the challenge, titled “Skyscraper Live,” will be broadcast worldwide live on Netflix at 9am. B: Oh my goodness, Taipei 101 is the world’s tallest green building. Is he crazy? A: Honnold is actually the climber in the 2019 film “Free Solo” that won an Oscar for best documentary, and was directed by Taiwanese-American Jimmy Chin and his wife. He’s a legendary climber. B: Didn’t Alain Robert, “the French Spiderman,” also attempt to scale Taipei 101 in 2004? A: Yes, but

A: There are always adventurers who want to conquer Taipei 101 as a world-class landmark. Didn’t someone once parachute from the top of it? B: Yeah, that’s right. Austrian extreme sportsman Felix Baumgartner once parachuted from the rooftop observation deck in 2007 without permission. He died earlier last year in a powered paragliding crash at the age of 56. A: Hollywood superstar Tom Cruise also almost jumped off Taipei 101 for “Mission Impossible 3.” B: What? But I didn’t see the building in the movie. A: The news says that the film’s producers applied to the Taipei City

For many introverts, shy individuals and people with social anxiety, mingling at parties is often draining or arouses uncomfortable emotions. The internal debate about whether or not to attend large get-togethers can get especially intense during the holiday season, a time when many workplaces celebrate with cocktail hours, gift exchanges and other forms of organized fun. “Some people are just not party people,” City University of New York social work professor Laura MacLeod said. “With a workplace holiday party, there’s a pressure to be very happy and excited. It’s the end of the year, it’s the holidays, we’re all feeling grand.

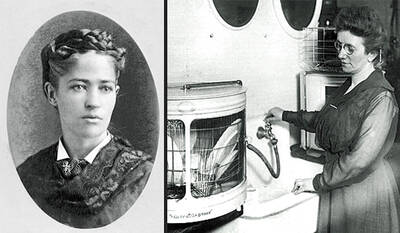

Twelve dinner guests have just left your house, and now a tower of greasy plates stares back at you mockingly. Your hands are already wrinkling as you think about scrubbing each dish by hand. This nightmare bothered households for centuries until inventors in the 19th century tried to solve the problem. The first mechanical dishwashers, created in the 1850s, were wooden machines with hand cranks that splashed water over dishes. Unfortunately, these early devices were unreliable and often damaged delicate items. The real breakthrough came in the 1880s thanks to Josephine Cochrane, a wealthy American socialite. According to her own account,