The theory of the shared origin of painting and calligraphy, and its practical application, comes from the special characteristics of Chinese writing and the Chinese brush, the implement used in both writing and painting. Bilingual Arts has previously looked at how the surface textures of mountains and rocks were built up using the cunfa technique in landcapes, and how continuous strokes were used in figurative painting. This month we explore a classic combination of painting and writing technique: Bamboo in ink.

Wen Tong (1018-1079), style name Yuke, was an official of the Northern Song Dynasty. He excelled in poetry and prose, as well as painting and calligraphy. He was the first to paint bamboo using only monochrome ink, and for this he was a huge influence on those who came after him.

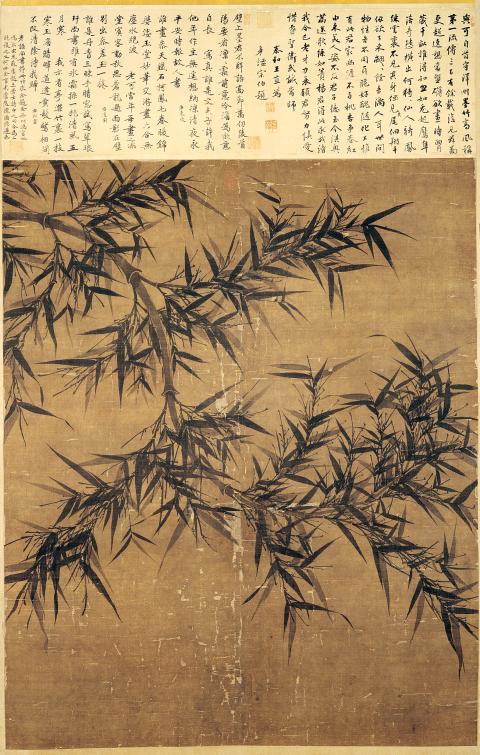

Wen Tong’s Bamboo in Monochrome Ink (photo 1), in the collection of the National Palace Museum, depicts a bamboo branch with lush leaf cover hanging down from a cliff, snaking diagonally down from the upper left of the painting. The bamboo leaves are painted in ink, in layers of dark and faint tones, to produce a sense of space and rhythm.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

Looking closely, you can see how Wen Tong drew the center of the brush across the silk to create the bamboo stalks, lifting the brush and using the tip to paint the nodes, leaving a white line to delineate the divide. For the bamboo leaves, the artist uses two techniques: Starting the stroke with tip concealed and concluding the stroke with the tip revealed. He also used an ingenious turn of the brush for the end of some of the leaves (see detail, photo 2), beautifully expressing the suppleness and pliancy of the leaves. The realistic depiction of the fine twigs is achieved through a combination of dense ink, thin lines and the dun dian pause.

Even though Wen Tong relied entirely on variations in ink and calligraphic strokes, he was in no way hampered by the simplicity of the tools available to him. The realism he achieves with his calligraphic brushwork, when one would have expected something far more abstract, is impressive.

According to historical records, there were thick bamboo forests in the area in which Wen Tong lived. He would spend long hours in the hot sun scrutinizing the diverse ways in which bamboo would grow, and put his brush to use in depicting what he had seen. There is a Chinese proverb, 胸有成竹, which literally means “bamboo in the breast.” This was derived from a description of Wen Tong by his close friend and cousin Su Shi, (Su Dongpo), and refers to confidence born of thorough preparation.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

(Translated by Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

「書畫同源」的理論與實踐,來自中文文字與書寫工具(毛筆)的特性。我們已在雙語藝術單元中,介紹過營造出山石體積的皴法、以連綿線條羅織出的人物像;本月我們將介紹另一在「畫」與「寫」之間的典型──墨竹。

文同(一○一八~一○七九)字與可,為北宋文官,詩文書畫兼擅,首創以水墨單色畫竹,對後世影響極大。

文同此幅《墨竹》(圖一),現藏台北故宮博物院,描繪枝葉繁茂的一支竹,由懸崖倒伸、自畫面的左上方蜿蜒而下。竹葉以或濃或淡的墨畫出,層層添加在枝幹上,形成豐富的空間層次與節奏。

細觀之,文同畫竹竿用圓渾中鋒行筆;竹節採鉤筆、留白,上下相扣。竹葉的畫法是起筆藏鋒、收筆露鋒,有些竹葉的葉尖還有巧妙的轉面(圖二),把竹子柔韌的葉片質感表達得絲絲入扣。而看似寫實的細小竹枝,其實是以濃墨、細線、頓點所構成。

文同以書法豐富的筆墨變化描繪竹的外貌,完全不因繪畫工具的簡單而受侷限──此畫皆用書法的筆法,理應抽象,但卻寫實至極。

史載文同所居之地有茂密竹林,他常不畏酷暑長時間仔細觀察揣摩竹子的各種姿態,而下筆繪竹則一氣呵成。成語「胸有成竹」,便是源自蘇軾(蘇東坡)對其摯友及表兄文同的描述。

(台北時報林俐凱)

In most cities, food waste is often regarded as one of the most troublesome types of waste: it has a high moisture content, spoils easily and produces strong odors. If not handled properly, it can cause serious sanitation and environmental problems. From the perspective of the circular economy, however, food waste is not “useless leftovers,” but rather an organic resource that has yet to be effectively utilized. The core principle of the circular economy is to break away from the linear model of “production–consumption–disposal,” allowing resources to circulate repeatedly within a system and extending their useful life. Food waste occupies a

A: Google has unveiled its 2025 Year in Search chart. No. 10 to No. 6 are: Typhoon Podul, Chinese drama “Love’s Ambition,” tariffs, US President Donald Trump and singer Khalil Fong’s death. B: Wow, actress Rosy Zhao’s new drama is so popular. So what are the top five? A: No. 5 to No. 1 are: Gemini, hanzii.net, NT$10,000 cash handout, entertainer Big S’ death and earthquakes. B: Hasn’t Trump topped this year’s most-searched people chart? A: Yup, and he’s closely followed by cheerleader GuoGuo Chiang at No. 2, whose husband Zack Fanchiang is also at No. 8. Apparently, people are curious about her extramarital

In June, headlines shocked the art world when a visitor damaged a 17th-century painting at the Uffizi Galleries in Florence, Italy, while posing for a photograph. This was not an isolated event. Recently, similar disasters have been reported worldwide, from a child damaging a Mark Rothko painting to a tourist breaking an exhibit by pretending to sit on it. Such incidents highlight why museum etiquette is increasingly crucial. First, we must recognize that art and historical objects are fragile. Once damaged, they may never regain their original condition. Many common actions, though harmless at first glance, can have grave consequences. For

對話 Dialogue 清清:後天就是聖誕節了! Qīngqing: Hòutiān jiùshì Shèngdàn jié le! 華華:但也是我們的行憲紀念日,從今年開始又恢復放假了。 Huáhua: Dàn yě shì wǒmen de Xíngxiàn Jìniànrì, cóng jīnnián kāishǐ yòu huīfù fàngjià le. 清清:只有一天吧?沒有彈性放假,對嗎? Qīngqing: Zhǐ yǒu yì tiān ba? Méiyǒu tánxìng fàngjià, duì ma? 華華:對,就是星期四休一天。 Huáhua: Duì, jiùshì xīngqísì xiū yì tiān. 清清:你那天有什麼安排? Qīngqing: Nǐ nèitiān yǒu shénme ānpái? 華華:我想吃聖誕大餐,然後跟家人交換禮物。 Huáhua: Wǒ xiǎng chī Shèngdàn dàcān, ránhòu gēn jiārén jiāohuàn lǐwù. 清清:聽說樓下的部門也辦交換禮物派對,我們要不要也辦一個? Qīngqing: Tīngshuō lóuxià de bùmén yě bàn jiāohuàn lǐwù pàiduì, wǒmen yào búyào yě bàn yí ge? 華華:喔!好啊!那你問問大家的意見吧! Huáhua: Ō! Hǎo a! Nà nǐ wènwen dàjiā de yìjiàn ba! 翻譯 Translation Qingqing: The day after tomorrow is Christmas. Huahua: It’s also Constitution Day in Taiwan. Starting this year, we get the day off again. Qingqing: