A powerful roar rocked the forest before the silhouette of a lioness appeared at an Indian reserve, a potent image of how conservation efforts have brought the creatures back from the brink.

In Gir National Park, Asiatic lions reign over a 1,900-square-kilometre expanse of savannah and acacia and teak forests, their last refuge.

For a few minutes, cameras clicked wildly from safari jeeps, but as night falls and visitors leave, the mighty cat has still not moved a paw.

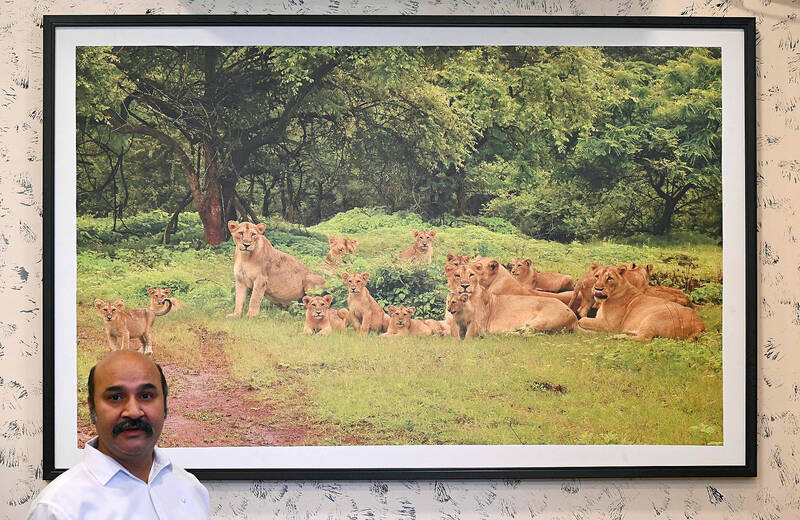

Photo: AFP

Gir’s success stems from more than three decades of rigorous conservation to expand the lions’ range, which now raises questions about the future of coexistence with humans.

Park chief Ramratan Nala celebrates the “huge success”: lion numbers have risen by a third in five years, from 627 to 891.

“It’s a matter of pride for us,” Nala said, the head of government forests in the sprawling Junagadh district of the western state of Gujarat.

Photo: AFP

The Asiatic lion, slightly smaller than their African cousins, and identified by a fold of skin along its belly, historically roamed from the Middle East to India.

By the early 20th century, only about 20 remained, nearly wiped out by hunting and habitat loss.

“They’ve been resurrected from the brink of extinction,” said wildlife biologist Meena Venkatraman.

Photo: AFP

‘OUR LIONS’

After India broke free from British rule in 1947, a local prince offered “his” lions sanctuary. In recent decades, the authorities have invested heavily by protecting vegetation, securing wells and roads, and even building a hospital. “The thing about lions is that if you give them space, and you protect them and you give them prey, then they do extremely well,” said Andrew Loveridge, from global wild cat conservation organisation Panthera.

In 2008, they were removed from the IUCN Red List of species threatened with extinction, and moved to the category of merely “endangered”.

Photo: AFP

Unlike in Africa, poaching is virtually absent.

“The local people support the conservation of Asian lions,” Nala said, reporting zero cases of poaching for more than a decade.

“These are our lions,” his deputy Prashant Tomas said. “People are very possessive about them.”

‘SECRET TO SUCCESS’

Local communities fiercely protect the lions for cultural, religious and economic reasons, because they attract tourists.

Loveridge said that people accepted some livestock would be lost.

“In general, they’re less likely to kill the lions in retaliation for livestock losses, which is something that is very prevalent in many sites in Africa,” he said.

“Indian wildlife managers have managed to contain that conflict, to a large degree — in many ways, that’s their secret to success.”

But rising numbers mean lions now roam far beyond the park.

About half the lion population ranges across 30,000 km2, and livestock killings have soared, from 2,605 in 2019-20 to 4,385 in 2023-24. There are no official figures on attacks on humans, though experts estimate there are around 25 annually. Occasionally, an attack hits the headlines, such as in August, when a lion killed a five-year-old child.

‘SPREAD THE RISK’

As lions move into new areas, conflicts grow. “They are interacting with people... who are not traditionally used to a big cat,” said Venkatraman.

And, despite their increasing population, the species remains vulnerable due to limited genetic diversity and concentration in one region.

“Having all the lions in a single population may not be a good idea in the long term,” she added. Gujarat has resisted relocating some lions to create a new population, even defying a Supreme Court order.

Nala pointed out that Gir’s lions are separated into around a dozen satellite populations.

“We cannot say that they are all in one basket,” he said.

Loveridge accepted that it “is starting to spread the risk a little bit.”

But he also warned that “relatively speaking, a population of 900 individuals is not that large”, compared with historic numbers of tens of thousands.

Long-term security of the species remains uncertain, but momentum is strong -- and protection efforts are having a wider impact on the wildlife across the forests.

Venkatraman described the lions as a “flagship of conservation.” “That means because you save them, you also save the biodiversity around.”

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South