For 35 years, American zoologist Laurie Marker has been collecting and storing specimens in a cheetah sperm bank in Namibia, hoping conservationists never have to use them.

But she worries that the world’s fastest land animal might be on the brink of extinction one day and need artificial reproduction to save it.

Marker says the sperm bank at the Cheetah Conservation Fund she founded in the southern African nation is a “frozen zoo” of cheetahs she’s been building since 1990. It would be utilized in a worst-case scenario for the big cats, whose numbers have dropped alarmingly in the wild over the last 50 years.

Photo: AP

“You don’t do anything with it unless until it’s needed,” Marker, one of the foremost experts on cheetahs, said at her research center near the Namibian city of Otjiwarongo. “And we never want to get to that point.”

Conservationists mark World Cheetah Day on Thursday with less than 7,000 of them left in the wild, similar numbers to the critically endangered black rhino. There are only around 33 populations of cheetahs spread out in pockets mainly across Africa, with most of those populations having less than 100 animals, Marker said.

Like so many species, the sleek cats that can run at speeds of 112 kilometers per hour are in danger from habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict and the illegal animal trade. Their shrinking, isolated groups mean their gene pool is shrinking also as small populations continuously breed among themselves, with repercussions for their reproduction rates.

Globally, cheetah numbers in the wild have dropped by 80 percent in the last half-century and they’ve been pushed out of 90 percent of their historical range.

Scientists believe that cheetahs already narrowly escaped extinction at the end of the last ice age around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, which first reduced their gene pool.

Marker said the lack of genetic diversity, along with the fact that cheetahs have 70 to 80 percent abnormal sperm, mean they might need help in the future.

“And so, a sperm bank makes perfect sense, right?” Marker said.

A COMMON TACTIC

Storing sperm is not unique to cheetahs in the wildlife world. It’s a tactic that conservationists have developed for other species, including elephants, rhinos, antelopes, other big cats, birds and others.

The value of animal reproductive research, Marker said, is seen in the desperate battle to save the northern white rhino from extinction.

There are just two northern white rhinos left, both females, making the species functionally extinct with no chance of reproducing naturally. Their only hope lies in artificial reproduction using northern white rhino sperm that was collected and frozen years ago.

Because both remaining northern white rhinos — a mother and daughter — can’t carry pregnancies, scientists have tried to implant northern white rhino embryos in southern white rhino surrogates. The surrogates haven’t managed to carry any of the pregnancies to term, but the conservation team has committed to keep trying to save northern white rhinos against all odds.

Other efforts around artificial reproduction have been successful, including a project that bred black-footed ferrets using artificial reproduction after they’d been reduced to a single wild population in Wyoming in the United States.

LAST RESORT

Marker doesn’t chase down cheetahs to collect their sperm but takes samples opportunistically. In Namibia, cheetahs are mostly in danger from farmers who view them as threats to their livestock, meaning Marker’s team are called out for cats that have been injured or captured and will collect samples while treating and releasing them.

Sperm samples can also be taken from dead cheetahs. “Every cheetah is actually a unique mix of a very small number of genes. We will try to bank every animal we possibly can,” Marker said.

The samples from approximately 400 cheetahs and counting are now stored at ultralow temperatures in liquid nitrogen at the Cheetah Conservation Fund laboratory. Marker’s research does not involve any artificial insemination as breeding wild animals in captivity is not allowed in Namibia.

Should cheetahs be threatened with extinction again, the first backup would be the roughly 1,800 cats living in zoos and other captive environments. But, Marker said, cheetahs don’t breed well in captivity and the sperm bank might be, like the northern white rhinos, the last resort.

Without it, “we’re not going to have much of a chance,” Marker said.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

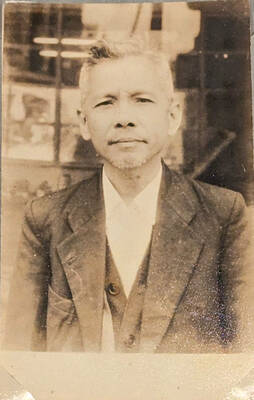

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name