Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear.

The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station.

Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan 1st Road (中山一路) and two and a half blocks west along Bade 2nd Road (八德二路) to the unassuming townhouse at Number 37. A prominent blue sign hanging out over the street marks this as the location of the First Publishing House (第一出版社), the company started by the late Ko Chi-hua, still in operation today.

Photo by Tyler Cottenie

AN ORDINARY HOME

The building’s decor is typical of the 1960s: an attractive mosaic tile pattern, now discolored with age, adorns the exterior wall, while the windows are covered by a colorful but less attractive metal grating. A decidedly unattractive corrugated steel structure on the roof, where the children used to play ping-pong, completes the facade.

Only after approaching the front door does it become apparent that this is also a museum. A sign above the front window informs visitors that this is the “Kua Ki Hua House,” using Ko’s Hoklo (better known as Taiwanese) name. The first floor is mostly taken up by display shelves for the publishing house’s books, but the audio tour still begins here.

Photo of exhibit at The Ke Qi Hua House museum

Look for the QR code for the tour app (Popworld) and search for “Ke Qi Hua” within the app to find the English version of the tour. The translation is clear and accurate, and the audio files themselves are of a high standard, with professional narration and background music suited to the content. It’s very easy to follow along with the tour, as the app also features a map of each floor and location pins for each point on the tour.

The house itself is visually unremarkable. The floors and lower walls are terrazzo with inlaid metal dividers, common at the time, while the upper walls and ceiling are simple, painted white concrete. The value of the tour lies not in the building itself but in the subtle touches that reveal who lived here, and the story of how they not only survived but prospered, despite the family being kept apart for 15 years.

At the back of the first floor is the house’s modest kitchen, where Tsai A-li prepared meals for their three children. Not only did she have to take care of the household and the publishing company, but she was also a teacher during the daytime. She did not have the time or energy to be too strict with the children, who nevertheless excelled academically and in the arts.

Photo by Tyler Cottenie

KO CHI-HUA: TEACHER, WRITER, INTERPRETER

The main feature on the second floor is the living room. Pictures of Ko Chi-hua through several decades hang on the walls and part of his extensive reading collection lines one wall. Books in Mandarin are the most numerous, including novels, dictionaries, poetry, and a full encyclopedia set, the Pan-Chinese Encyclopedia from 1982.

Two full encyclopedias in English (Encyclopedia Americana and World Book) reveal Ko’s interest in the world outside Taiwan and his proficiency in English. Before his second prison term, Ko was already well known for New English Grammar, a book he published based on worksheets he had created for his in-home cram school. At its peak, the book sold over 100,000 copies a year and helped support the family during Ko’s prison term.

Photo by Tyler Cottenie

More numerous than the English books, however, are the Japanese ones. Born in 1929, Ko grew up during the Japanese era and was one of the few non-Japanese students to be admitted to the Takao Senior High School (now Kaohsiung’s most elite public high school). When he graduated, Taiwan had already been taken over by the Republic of China, but his literacy in Japanese remained strong, so much so that he wrote his semi-autobiographical book Taiwan Prison Island (台灣監獄島) in Japanese, nearly half a century later. It was only released in Mandarin after his death, when the translation was completed by his son.

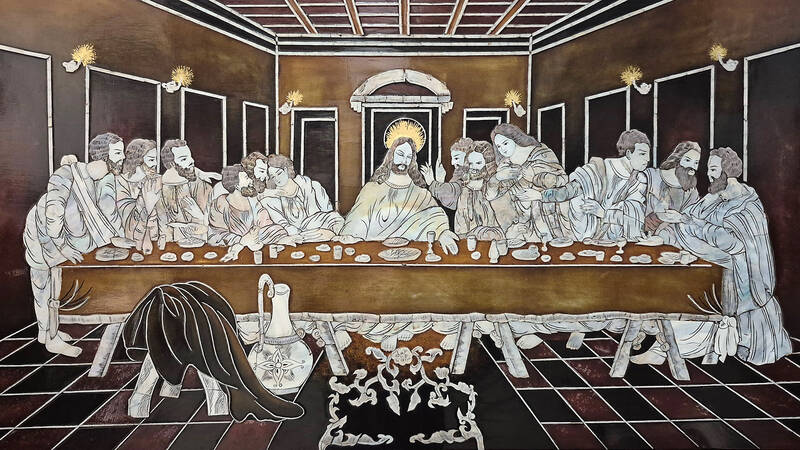

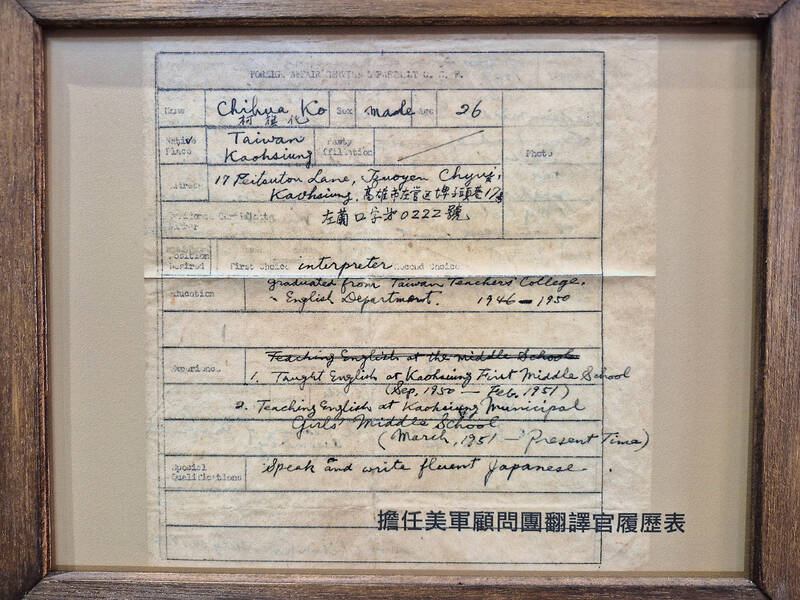

Further evidence of his proficiency in English and familiarity with Western culture can be found in the one artifact on display that is actually more accessible to English speakers: a record of his application for employment as an interpreter for the American military, handwritten in English. Other touches of foreign influence include a box of Chivas Regal scotch hidden behind a Chinese tea set, as well as a lacquer painting of The Last Supper and a plaque declaring that “Jesus is Lord of Our House.”

The study on the third floor provides a deeper glimpse into Ko’s career as a writer, which included a fictional novel, books of poetry, an autobiographical novel and plenty of English teaching material.

Photo by Tyler Cottenie

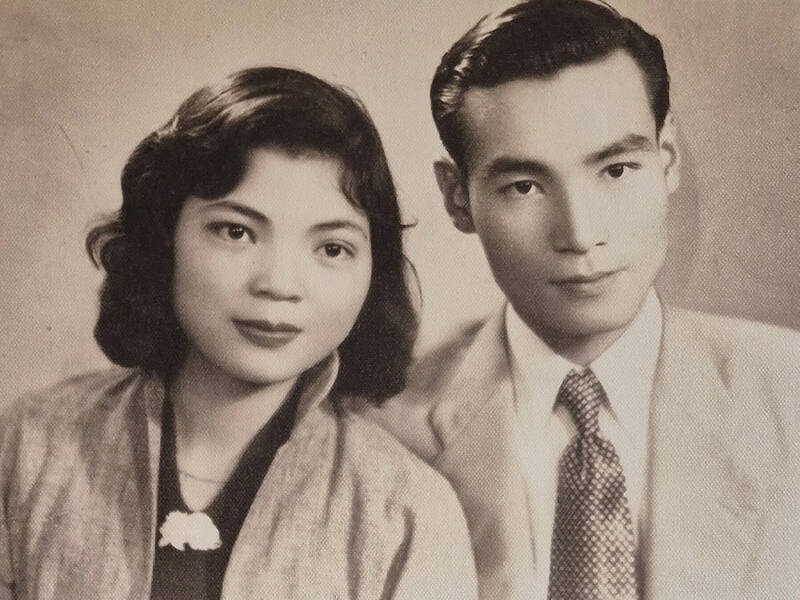

A FAMILY UNDER DURESS

On the same floor is Ko and his wife’s bedroom, where we learn more about their courtship and marriage. Ko had already been imprisoned for possessing a communist book before meeting his wife, a two-year sentence for which he was eventually compensated in 2000. Despite this black mark against his name, and against her family’s objections, Tsai A-li married Ko in 1955, and had three children with him, in 1956, 1958 and 1960. When Ko was arrested in 1961 and imprisoned again, this time for 15 years, great strain was placed on their marriage.

The largest space on this floor is dedicated to Tsai A-li and the three children, and how they coped with life without a father in the house for 15 years. This is certainly the most heart-wrenching part of the tour.

Photo of exhibit at The Ke Qi Hua House museum

To protect the young children from the harsh truth about their father, Tsai told them that he was away in the US. She would show them letters from their father made to look as if they came from the US, and would buy imported Christmas gifts “from their father” for the children at Christmas. The ruse came to a tearful end when the daughter discovered a Taitung address on one letter’s envelope and secretly wrote back to her father, who was imprisoned on Green Island at the time.

Stories like this, and the first meeting of the children with their father in prison, are told by Tsai and one of her sons. The English audio tour does a good job of summarizing the experience, but if you can understand written or spoken Chinese, the interactive displays here — with first-person narration from family members and copies of handwritten letters between Kaohsiung and Green Island — are really worth digging into.

Even if you only have a basic understanding of Bopomofo and some common characters, you may still be able to read the letter written by Ko’s son when he was in the first grade, begging his father to come home soon.

Photo by Tyler Cottenie

And while Ko did eventually come home, the fatherless youth experienced by Ko’s three children is something that no amount of money can ever buy back. It is just one of countless examples of suffering during the White Terror period, now open to examination and contemplation at this free museum in Kaohsiung.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades