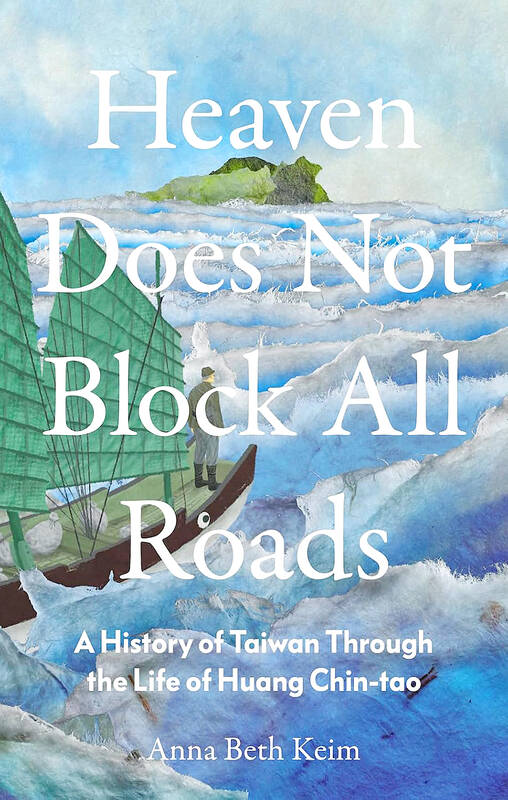

Speaking at the launch for this book in London last month, Anna Beth Keim described an almost 10-year process from writing to publication, which included many fruitless attempts to find a literary agent for the work.

“It was actually rejected by every single agent that I contacted,” she told an audience at the School of Oriental and African Studies. “And, just as a kind of Hail Mary, I reached out directly to Hurst.”

The small, independent UK publisher showed immediate interest and was not confined purely by commercial considerations. “I’ve never asked why they took a chance,” Keim says. “They’re one of the few left who can make these decisions to publish quirky books, not just thinking about the algorithm and selling to maximum number of people.”

Prior to the fateful pitch to Hurst, some of the “big deal” agents that showed a passing interest advised Keim to refocus the book as a more generalized history of Taiwan, while others pushed for a change of protagonist.

Both of these suggestions completely miss what makes this book special. As an “insider’s story,” it is perhaps unique in depicting key periods of Taiwan’s history over roughly a century through the life of a single person. This approach is not only much more interesting than a formulaic macrohistory — and there have been enough of these, of late — but extremely effective.

Through the figure of Huang Chin-tao (黃金島), we come to understand the complexity, confusion and anguish of Taiwanese identity, “the bumps and warts: the moral compromises of the colonized.”

No mistake: This is not a work that simply emphasizes Taiwan’s victimhood and perennial status as a hapless pawn in great power struggles. For, as Keim observes in her prologue, “stories like Huang’s offer a Taiwanese history that is not just about suffering or fragmented identity under various regimes, but stubborn resistance.”

And few figures exemplify this dogged determination better than Huang, who emerged unbroken from a series of seemingly catastrophic circumstances, over more than half a century, standing tall and unbowed. (Recounting her first meeting with Huang in his hometown of Taichung in 2016, when the 90-year-old showed up on motorbike, Keim recalls his “military bearing … firm handshake and a “spine [that] was ramrod straight.”)

But, more obviously, while commercial concerns over a limited audience for such a work are understandable, the request for a change of hero makes no sense. The “big deal agent” who had asked for this, explains Keim, had handled several authors whose books were later adapted into successful films.

“I was very excited talking to her,” says Keim. “And she wrote back and said, ‘I’ll take you on, but you have to find a different person — think about it like we’re watching a movie of his life.”

CONSISTENT REINVENTION

In fact, as Keim pointed out in her talk, that’s exactly what Huang’s life reads like, featuring, as it does, several episodes straight out of an “adventure story.” Apart from him being an unknown, the demand for someone else to lead this tale is baffling. Aside from being an excellent short history of Taiwan, it’s quite simply a hell of a story.

We’re thrown right in with a snippet from an astonishing episode — Huang’s escape by boat during a typhoon from a Republic of China-administered detention camp on China’s Hainan Island, where he had served as a mechanic in the Special Naval Landing Forces of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Born Huang Zhen-tao (黃圳島) in modern-day Taichung in 1926, as a Japanese schoolboy and soldier, he was known as Hiroshima Takeo, taking this surname because of the proximity of the traditional kanji character for hiro to the Chinese character for Huang, which, Keim writes, “allowed him to keep a bit of himself.”

This from a man who seemed to consistently reinvent himself throughout his life — to such an extent that one grasps to find a motivation or credo. It is interesting that, in reflecting on Taiwanese soldiers who defected to or even simply sympathized with their Chinese enemies, Huang accuses his compatriots of “having no center and no core.”

EXISTENTIAL INDIFFERENCE

As we learn when Keim pans out from the opening snapshot, Huang had enlisted as a 16-year-old in 1943, not from patriotic zeal but almost through a go-with-the-flow existential indifference.

Keim’s reflections on this during her presentation in London and in the text bring to mind Meursault, the antihero of Albert Camus’ classic novel The Stranger, who — with his refrain of cela m’est egal (it’s all the same to me), displays apathy toward societal norms and a disposition to go where the winds takes him. Another incident from Hainan involved the beheading of Chinese soldiers. In an interview with Huang, Keim asked about his feelings on witnessing this atrocity in “the land of [his] ancestors” She felt the habitually unflappable nonagenarian might reveal some compunction by association. “But he didn’t offer a reflection,” she said. “Number one, he didn’t have strong feelings of connection to China; I think also he was not one to philosophize or reflect.”

Instead, Huang was “a man of action,” charting his course based on a revulsion for injustice, irrespective of who was inflicting it.

In this regard, he can be considered a natural successor to the Japanese-era activists of the Taiwan Cultural Association who, as Chris Horton observes in his — rightly accoladed book Ghost Nation — did not so much advocate for independence as demand decency and dignity.

SPITEFUL SPAT

Finding these qualities in short supply under Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule, Huang took to the mountains with the 27 Brigade (二 七部隊) guerrilla force — here referred to as Troop 27.

The descriptions of his participation in the Battle of Wuniulan (烏牛欄) are, as far as I’m aware, the only in-depth, firsthand English-language accounts of these events and Keim does a brilliant job of communicating them.

Later, Huang would butt heads with fellow 27 Brigadier Chung Yi-jen (鍾逸人) about the specifics, with Keim observing that the pair “if left to their own devices would have been cursing each other in public.”

Much more could be added here: Huang’s flight in wake of the 228 Incident crackdown, evasion of authority through enlistment in the Republic of China military — “the most dangerous place is the safest place” — and decades-long incarceration, mostly on Green Island; finally, his transition to democracy activist.

In this last incarnation, Huang confounded people with gestures such as a convivial meeting with newly elected President Ma Ying-jeou in 2008. Those of the younger activists who knew of him were irked.

Quoting Chou Fu-yi (周馥儀), a prominent activist in the 2014 Sunflower movement, Keim emphasizes “the courage to act.” She concludes with reflections on Huang’s “irrepressible spirit” — a fitting hat tip to an impressive man and the country his life so aptly reflects.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

We have reached the point where, on any given day, it has become shocking if nothing shocking is happening in the news. This is especially true of Taiwan, which is in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), uniquely vulnerable to events happening in the US and Japan and where domestic politics has turned toxic and self-destructive. There are big forces at play far beyond our ability to control them. Feelings of helplessness are no joke and can lead to serious health issues. It should come as no surprise that a Strategic Market Research report is predicting a Compound