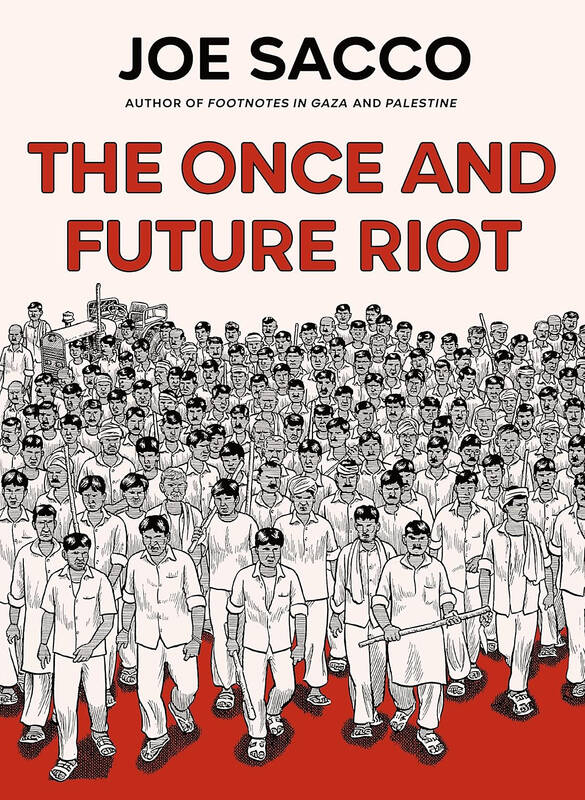

Joe Sacco is one of a very small number of graphic novelists who have smashed through into the mainstream. His masterwork is Palestine, a collected volume of single-issue comic books he created in the 1990s, documenting the violence in Gaza. His technique is to embed as a journalist in a war zone and interview people on the street, telling their stories with pictures. Lessons on global politics emerge from ultra-local conflict and depictions of day-to-day life.

Palestine propelled Sacco to fame, drawing comparisons with Maus, Art Spiegelman’s two-volume saga about Polish Jews during the Holocaust with Nazis portrayed as cats, and Jews as mice. These works are sold prominently in bookshops, not in musty basements packed with racks of polyethylene-sheathed superhero comics. Alongside a couple of others, Maus and Palestine signaled that graphic novels, as they became known, could be serious works of fiction, nonfiction and journalism. Palestine itself is as depressingly relevant today as it was in the 1990s. In December 2023, it was reprinted for the first time in a decade, after selling out following the Oct. 7 attacks.

The historical backdrop to Sacco’s work is colonialism. Just as Palestine charts the long-term ramifications of the Balfour declaration, this new book explores the legacy of the disastrous and inherently violent act of Indian partition in 1947. It’s a history told through the lens of a seemingly small-scale, parochial conflict in a very rural part of Uttar Pradesh, northern India, more than six decades after the British imposed a chaotic division of the country along very poorly devised religious lines. Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy of British India, lacking any humility or foresight, declared: “I shall give you complete assurance. I shall see to it that there is no bloodshed and riot.”

Sacco’s focus is the Muzaffarnagar riots of 2013, but he spends time documenting the history of the region and the tensions that foreshadowed them. Their exact cause is disputed: a Jat Hindu woman was “eve-teased” — a grim euphemism for public sexual harassment — by a Muslim man, who was then killed by her brothers, who were subsequently killed themselves. Or was it a traffic incident that spiraled into sectarian scrapping, escalating into murder by rampaging gangs?

If the trigger remains a mystery, the outcome is well documented: clashes between two communities, dozens killed, hundreds injured and tens of thousands displaced. At every juncture, politicians and religious leaders fail to maintain peace and control.

And so this becomes a story of the uneasy relationship between democracy and sectarian politics, and the brutality that constantly lurks in the shadows. It charts how rumor and misinformation fuel chaos — a video on Facebook purporting to show a local Jat boy being lynched was pivotal in igniting feverish violence, though it turned out to be years old and from Afghanistan.

The riots lasted a few days, with the army eventually brought in to quell the violence. Sacco chronicles its aftermath in camps the dispossessed — both Jat and Muslim, but mostly Muslim — were forced into, and the attempts at reparations, which were inept and possibly corrupt.

The “future riot” of the title invokes the idea that violence is a perennial feature of democratic processes in India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s rise was at least partly fueled by riots in Gujarat in 2002, after a train containing Hindu pilgrims was set on fire and Muslims were blamed. Anti-Muslim prejudice following the Muzaffarnagar riots themselves benefited Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP. A decade later, the atmosphere in Uttar Pradesh, and the wider country, remains volatile. In the concluding pages, Sacco turns to a question of global significance: does a democracy that foments violence risk being overwhelmed by it?

There’s wit and realism in the panels and art. It’s dynamic and clear, and the people seem less like caricatures than in Palestine. Vox pops punctuate the narrative, a reminder of the subjective experience of people on the street, in the midst of the action. There is, however, a strange phenomenon I’ve not seen before in 40 years of reading comics. The skin tone of all of the protagonists is dark, and the shading is done not by cross-hatching, but by parallel horizontal lines. Once I noticed it, it became distracting, like TV interference on every character’s face, and I couldn’t unsee it. This may seem like a pathetically trivial point, but comics are a visual medium, and you have to get on with the art. Get over it, I told myself, because the story is important and compelling, but it niggles.

Above all, Joe Sacco is a journalist, and this is journalism. The format, of which he is almost the only exponent, has a subjectivity absent from traditional approaches. The memories of the protagonists are sometimes contradictory, but Sacco includes them nonetheless. The graphic novel — a wholly unsatisfactory descriptor — can contain all the complexity of a tumultuous politics. In an era when long-form journalism is under pressure, and political analysis filleted to morsels, Sacco’s work is a lifeline.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In