The focus of Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value may be small and limited — one Norwegian family struggling to connect and communicate — and yet its emotional scope is downright cosmic. This is a film about life in the arts, about fulfillment and forgiveness, about performance, about stories true and falsely remembered, about home, about trauma, about allowing oneself to be seen and about some really excellent sweaters.

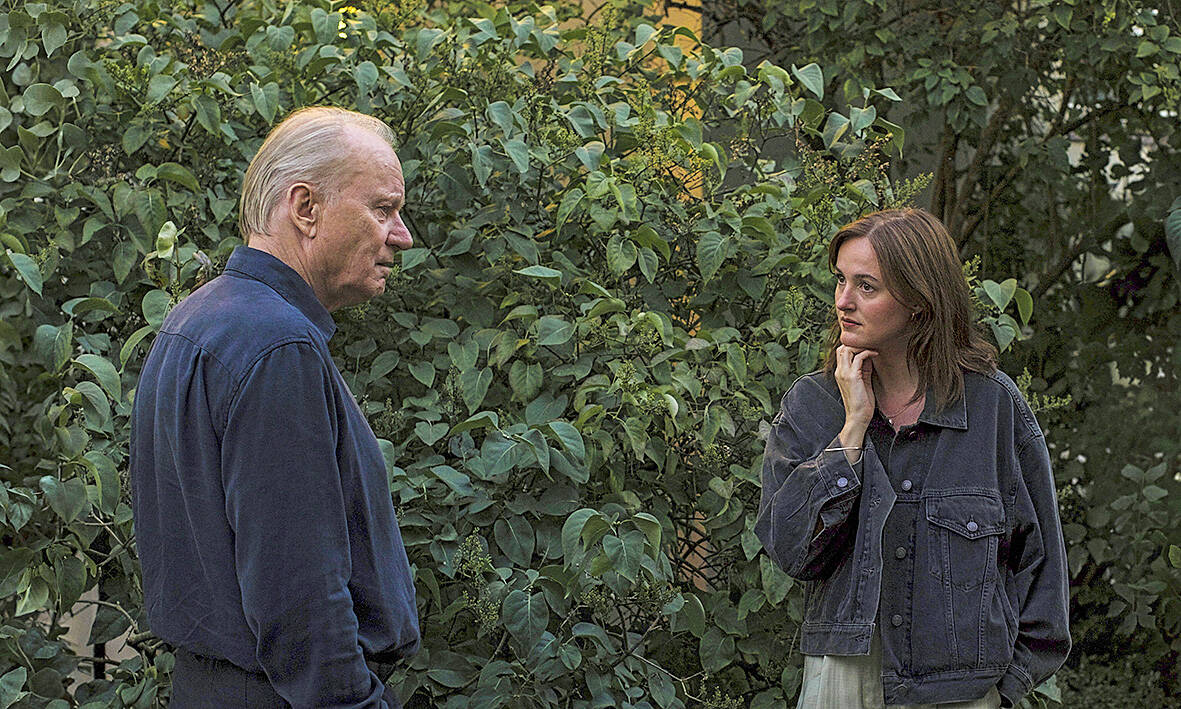

And at its heart is Stellan Skarsgard, doing some of his finest work in years as an acclaimed film director, Gustav Borg, who always chose his work over his family. Gustav is a familiar type, the kind of charismatic narcissist that professions like film director seem to attract and, often, exaggerate. He’s the kind who’s able to forge deep and meaningful connections with actors he’s just met and will only know for a few months that will produce great and lasting art. Yet his own daughters, Nora ( Renate Reinsve ) and Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas), may as well be strangers. Now with his career in danger of fading into retrospective territory, he’s trying to right those wrongs (and, you know, make a comeback) the only way he knows how: Making another movie. Some people never learn.

What better time to approach Nora about starring in it than right after her mother and his ex-wife’s death? It’s not so random: Nora is a rather celebrated actor in Oslo, though her preferred medium is the stage. She’s so good, in fact, that she continues to get lead roles despite being what one might describe as a difficult and unreliable member of the company. In an early scene, we watch her attempt numerous times to flee right as the curtain is about to go up. But Gustav doesn’t go see her plays. And she doesn’t care about his films, or him. He’s a drunk who was never there, she says. And so, without even reading the script that he excitedly says he wrote for her, she turns down the offer.

Photo: AP

The wounds run deep in this family, tethered to a home that has spanned generations and all of the highs and lows of life through the decades, including Gustav’s mother’s imprisonment torture during World War II. It can sound tiresome and cliche to describe places and things as characters, but the extended metaphor here is lovely and real, a physical space that is metaphorically the only thing tying them together. Gustav even wants to use it as a set for his film, which gets a second life when he connects with an American movie star named Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning) who is desperate to do something meaningful.

Soon comes the Netflix money, and some fun “inside show business” moments as Rachel prepares to play a difficult-to-crack character inspired by Gustav’s mother, who many years ago died by suicide in their home. There are shades of Persona as Rachel dyes her hair to match Nora’s and tries to understand not just the character but Nora as well.

When Rachel decides to drop out of the project, Gustav slips into an unexpectedly tender and fatherly mode, perfectly understanding, and comforting. When he cradles her head in with a gentle hug, it’s a lovely moment that’s laced with a melancholic truth: This is not something that Gustav has ever, or will ever, be able to do with his own kids.

Photo: AP

In this group of wonderful performances, Lilleaas may be the real breakout for American audiences. As Agnes, she’s the one who her father chose to star in one of his films as a child and then walked away from acting entirely. Out of the bunch she seems to be the most well-adjusted, with a husband and son and ordinary concerns about money and protecting her older, more fragile sister. But beneath the surface, she has lingering pain too: For a brief moment, she was the center of her father’s world, and then it was gone. When he asks her if he can use her young son in his new film, the reaction is visceral and charged.

As in life, things kind of work themselves out and also kind of don’t. Trier and his longtime cowriter Eskil Vogt have deftly crafted a deeply humane and relatable story that feels whole and satisfying and cinematic without resorting to trite and tidy resolutions and redemptions.

It’s a tall task to follow up a smash like The Worst Person in the World, but Sentimental Value rises to the occasion: Mature, sharp, bittersweet and maybe even a little hopeful.

Photo: AP

Photo: AP

The Lee (李) family migrated to Taiwan in trickles many decades ago. Born in Myanmar, they are ethnically Chinese and their first language is Yunnanese, from China’s Yunnan Province. Today, they run a cozy little restaurant in Taipei’s student stomping ground, near National Taiwan University (NTU), serving up a daily pre-selected menu that pays homage to their blended Yunnan-Burmese heritage, where lemongrass and curry leaves sit beside century egg and pickled woodear mushrooms. Wu Yun (巫雲) is more akin to a family home that has set up tables and chairs and welcomed strangers to cozy up and share a meal

Dec. 8 to Dec. 14 Chang-Lee Te-ho (張李德和) had her father’s words etched into stone as her personal motto: “Even as a woman, you should master at least one art.” She went on to excel in seven — classical poetry, lyrical poetry, calligraphy, painting, music, chess and embroidery — and was also a respected educator, charity organizer and provincial assemblywoman. Among her many monikers was “Poetry Mother” (詩媽). While her father Lee Chao-yuan’s (李昭元) phrasing reflected the social norms of the 1890s, it was relatively progressive for the time. He personally taught Chang-Lee the Chinese classics until she entered public

Last week writer Wei Lingling (魏玲靈) unloaded a remarkably conventional pro-China column in the Wall Street Journal (“From Bush’s Rebuke to Trump’s Whisper: Navigating a Geopolitical Flashpoint,” Dec 2, 2025). Wei alleged that in a phone call, US President Donald Trump advised Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi not to provoke the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Taiwan. Wei’s claim was categorically denied by Japanese government sources. Trump’s call to Takaichi, Wei said, was just like the moment in 2003 when former US president George Bush stood next to former Chinese premier Wen Jia-bao (溫家寶) and criticized former president Chen

President William Lai (賴清德) has proposed a NT$1.25 trillion (US$40 billion) special eight-year budget that intends to bolster Taiwan’s national defense, with a “T-Dome” plan to create “an unassailable Taiwan, safeguarded by innovation and technology” as its centerpiece. This is an interesting test for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and how they handle it will likely provide some answers as to where the party currently stands. Naturally, the Lai administration and his Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are for it, as are the Americans. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is not. The interests and agendas of those three are clear, but