US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op.

Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.”

But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it has deepened ties in recent years.

Photo: AFP

“The brutal reality is that Kim Jong-un had no incentive to participate,” said Lee Seong-hyon, a visiting scholar at the Harvard University Asia Center.

“It was a fundamental miscalculation by Washington to believe he would,” said Lee.

Trump’s repeated overtures instead represented a “victory” for the North Korean leader — offering him and his nuclear program a massive degree of credibility, Lee said.

“President Trump gave Kim a massive, unearned concession,” he said.

The pair — who Trump once famously declared were “in love” — last met in 2019 at Panmunjom in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating the two Koreas after the US leader extended an invitation to Kim on Twitter.

That overture to Pyongyang spearheaded by Trump eventually collapsed over the scope of denuclearization of the North and sanctions relief. Since then, North Korea has declared itself an “irreversible” nuclear state and forged close links to Russia, sending troops to support Moscow in its war on Ukraine.

Kim is now in a “pretty sweet spot,” said Soo Kim, a former CIA analyst.

“Russia’s backing is probably one of the most decisive factors strengthening and cementing North Korea’s strategic hand these days,” she said.

“He maintains the upper hand, which makes it easier for him to pass on Trump’s invitation,” Kim said.

Heading home from South Korea and a meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping (), Trump said he had been too “busy” to meet Kim, though he added he could return.

The scene stood in stark contrast to 2019, when denuclearization and sanctions relief talks in Hanoi, Vietnam, collapsed in dramatic fashion — leaving Kim to endure a long train journey back to Pyongyang with no deal in hand.

Vladimir Tikhonov, Korean Studies professor at the University of Oslo, said that experience had left Pyongyang sore.

“They don’t want to venture forward too rushingly,” he said.

Instead, Tikhonov said, Pyongyang may be holding out for more specific proposals from Trump, including formal diplomatic recognition and sanctions relief without denuclearization.

FRIENDS LIKE THESE

And closer alliances elsewhere mean Kim has little reason to chase approval from Washington.

This week, Pyongyang’s foreign minister Choe Son Hui headed to Moscow, where she and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to strengthen bilateral ties.

Analysts say North Korea is receiving extensive financial aid, military technology and food and energy assistance from Russia.

That has allowed it to sidestep tough international sanctions imposed over its nuclear and missile programs that were once a crucial bargaining chip for the United States.

Freeflowing trade with China — which soared to its highest level in nearly six years last month, according to analysts — has also helped ease Pyongyang’s economic isolation.

Last month, Kim appeared alongside Xi and Russia’s Vladimir Putin at an elaborate military parade in Beijing — a striking display of his new, elevated status in global politics.

Kim now has “no reason to trade this new, high-status quo for a photo-op” with Trump, said Harvard’s Lee.

Kim has a “strategic lifeline from Russia and China, and he sees the US-China competition as a long-term guarantee of his own maneuverability.”

The North Korean leader is now operating from a “position of strength.”

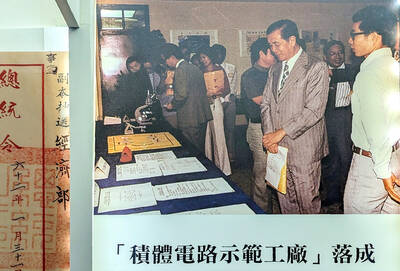

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

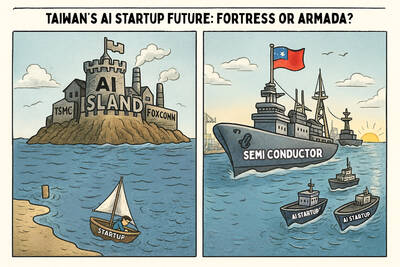

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders