Every time rains falls on the famous basalt columns at Daguoye (大?葉) in Penghu County’s Siyu Township (西嶼), carbon dioxide is removed from the Earth’s atmosphere.

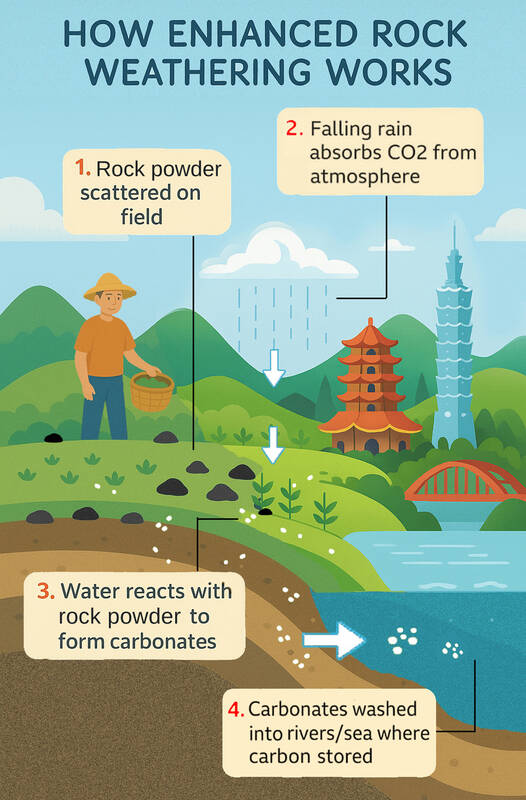

Gaseous CO2 dissolves in rainwater, forming carbonic acid. Even if the rainwater is unpolluted — not so-called “acid rain” — it’s sufficiently acidic to react with the rock surfaces it flows over, breaking down minerals and releasing dissolved ions. This process, called “weathering,” converts what was carbonic acid into dissolved bicarbonate ions.

Whether it’s washed into the sea that day (the cliff at Dagouye is less than 150m from the ocean) or a month later, the bicarbonate stays in the water. The slow circulation of deep ocean water keeps the carbon locked down. Corals and plankton draw on marine bicarbonate to build their shells and skeletons. When they die, their skeletals accumulate on the seabed, eventually forming limestones that sequester the carbon for millions of years.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This natural phenomenon is inspiring scientists, including some in Taiwan, to ask if it can be replicated and scaled up, to capture meaningful amounts of carbon and help bring CO2 levels closer to the 350 ppm considered safe. (As of Sept. 26, atmospheric carbon dioxide was 424.29 ppm.)

MULTIPLE BENEFITS

A recent experiment in New Taipei City’s Sanjhih District (三芝) suggests that what researchers call enhanced rock weathering (ERW) has promise, and not just as a carbon-removal technology.

AI assisted illustration by TT

The three-way collaboration between Tse-Xin Organic Agriculture Foundation (TOAF, 慈心有機農業發展基金會), National Taiwan University’s Department of Agricultural Chemistry and the Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences at Kyoto Prefectural University, ran from August 2023 to October last year. The results, which were reported by Reccessary on Aug. 21 but which have yet to appear in a scientific journal, showed that applying a combination of basalt powder and organic matter to the land boosted carbon storage by 20.5 percent.

Even more striking was the effect on crop yields. Compared to adjacent plots to which nothing was applied, those amended with basalt and organic matter produced more than twice as much corn and Cenchrus alopecuroides (an ornamental grass).

In a May 17 report on its Web site, the Australian Broadcasting Corp gave precedence to basalt’s potential to cut farmers’ fertilizer bills over its capacity for carbon removal. Reduced agrochemical consumption doesn’t only help farmers, however; the manufacturing, transportation and field use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers was in 2018 responsible for 2.1 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to a paper published in Scientific Reports (Aug. 25, 2022). What’s more, excessive use of inorganic fertilizers reduces the richness and diversity of bacteria and fungi in soil.

Photo: Liu Yu-ching, Taipei Times

So far, ERW research has focused on agricultural land, and not just because rock particles act as a slow-release fertilizer. Because it’s frequently tilled and watered, farmland is thought to be a better venue for carbon-capturing chemical reactions than forests, grasslands or parks. What’s more, modern farms are already equipped to spread dry powders like fertilizers and agricultural lime, making the logistical side of deploying rock dust simpler and more cost-effective.

Discussion of the Sanjhih experiment touched briefly on another benefit of ERW. Basalt rock dust releases inorganic macro and micro-nutrients (such as calcium, magnesium, phosphorus and potassium) which are essential if crops are to grow well and the humans who eat them are to thrive. (It’s not clear if basalt dust is as readily available to Taiwanese horticulturalists as it is to their North American counterparts. Pumice grains — which gardeners use to improve soil drainage and aeration — should work almost as well because they’re volcanic in origin, and they can be ordered from local companies.)

The Reccessary report quoted Atsushi Nakao, a Japanese scholar associated with the Sanjhih project, as saying that applying basalt powder adjusted the site’s soil pH from 5.1 to 5.7, a level it maintained throughout the 15 months of the experiment. Spreading basalt dust could be a way, he suggested, to improve crop growing conditions in those parts of Taiwan where acidity makes farmland suboptimal.

The results of an experiment on a sugarcane plantation in Australia’s tropical northeast, however, indicate that in strongly acidic soils, ERW might be ineffective for CO2 removal. This seems to be because the stronger acids that are present do more to weather the basalt than carbonic acid.

Increased soil alkalinity will cause a rise in the pH of the waterways receiving runoff. In turn, this will impact the sea. If widely deployed, ERW could help counter ocean acidification, a phenomenon researchers are taking very seriously indeed. Exacerbated by mankind’s massive carbon emissions, it’s feared that acidification could disrupt the marine food web by making it more difficult for calcifying organisms (like corals, shellfish, and certain plankton) to build and maintain their shells and skeletons.

The world has an abundance of basalt and other volcanic rocks, but applying huge amounts of rock dust in the hope it’ll result in carbon sequestration and a less acidic ocean could cause sudden, localized spikes in pH that are likely to disrupt freshwater ecosystems. But there’s another reason why ERW could be a non-starter in many parts of the world.

THE ENERGY ISSUE

Turning boulders into rock particles and transporting the latter to suitable locations is energy intensive. As a paper in Frontiers in Climate (July 22, 2022) puts it, “Small grain sizes (with high surface areas) are favorable for fast reaction rates in the system, but the comminution of rock to fine grain sizes implies energy costs that may render [ERW] less attractive.”

Depending on the type of rock and the size of the final product, crushing and grinding one metric ton of rock requires between 10 kWh and 25 kWh. We have a good idea how much carbon dioxide generating that amount of power in Taiwan will put in the atmosphere — 5.4kg to 13.6kg — but assessing the rate at which ERW draws down carbon is much more difficult.

A report published Aug. 15 last year for the UK’s Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST) acknowledges that the “timescales and permanence of CO2 removal is poorly quantified for ERW, due to a lack of evidence from long-term field trials, and relatively small changes in chemistry from smaller trials.”

Barriers to scaling up rock extraction and a lack of “standardized techniques for measuring and verifying any carbon dioxide removal” haven’t stopped the emergence of commercial ERW operations through which businesses can purchase carbon offsets, the POST report goes on to say.

One such company is London-based UNDO Carbon, which so far has spread 303,390 metric tons of silicate rock over 20,000 hectares of farmland in the UK and Canada. UNDO’s Web site says its ERW activities will draw down 220kg of carbon per metric ton of rock material. That estimate, which doesn’t appear to factor in any drop in greenhouse gas emissions due to reduced fertilizer use, suggests ERW could contribute positively to the fight against climate change.

Some countries, among them Australia, are fortunate in that they can ignore the extraction-and-grinding part of the equation. Many of Australia’s most valuable mineral deposits are beneath layers of basalt; mining companies remove it, then crush it to different sizes for commercial uses such as landscaping. And, as the Australian Broadcasting Corp pointed out, “demand for the dust and finest gravel left over is low.”

Project Drawdown, an NGO that advances science-based climate solutions and strategies around the world, says on its Web site that ERW “is not yet ready for large-scale deployment as a climate solution.” The technology is plausible and it could make enough of an impact to really matter, yet it isn’t consistently effective. Nor is it cheap. The NGO says that it “will ‘keep watching’ this potential climate solution.”

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move