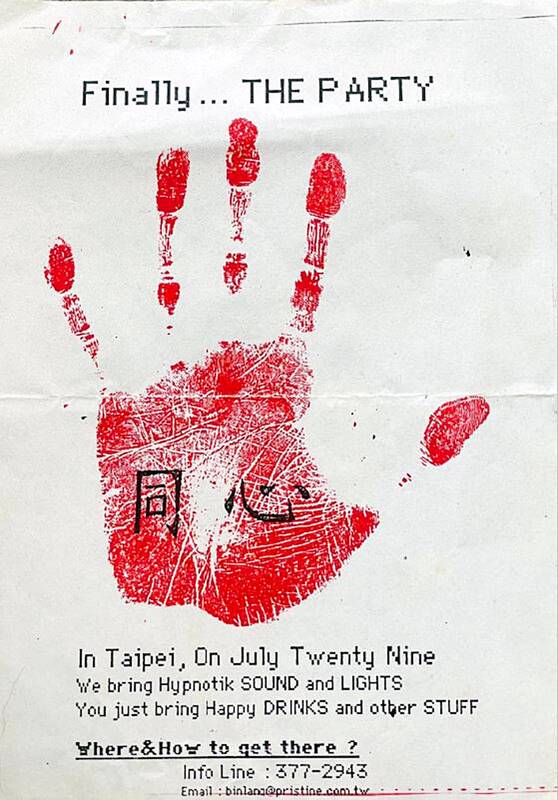

In July of 1995, a group of local DJs began posting an event flyer around Taipei. It was cheaply photocopied and nearly all in English, with a hand-drawn map on the back and, on the front, a big red hand print alongside one prominent line of text, “Finally… THE PARTY.”

The map led to a remote floodplain in Taipei County (now New Taipei City) just across the Tamsui River from Taipei. The organizers got permission from no one. They just drove up in a blue Taiwanese pickup truck, set up a generator, two speakers, two turntables and a mixer. They used a junked table for the DJ booth and set up plywood sheets to block the wind. There was no admission fee. Around a hundred people showed up and danced till dawn.

Held on July 29, 1995, it was Taiwan’s first ever rave.

Photo: courtesy of DJ @llen

30 YEARS ON

“You know, 30 years ago. It’s like, I can’t believe it,” said Allen Chen (陳宏愷), the rave’s organizer and DJ, interviewed last week by phone.

Chen and other DJs on Saturday will commemorate and to some extent recreate that first rave from 1pm to 9:30pm in New Taipei City’s Sinjhuang District (新莊) under the Zhongshan Bridge (中山橋).. The location is very close to the original site, but this time they have event permits and are selling tickets (NT$500 in advance, NT$800 door). Since the party happens in part during daylight hours, they opted for the covered bridge location to keep it out of the sun.

Photo: courtesy of DJ @llen

‘GODFATHER OF ELECTRONIC MUSIC’

Chen, known as DJ @llen, is long regarded as Taiwan’s “godfather of electronic music.” He’s DJed in global dance meccas like Ibiza, Spain and at a million person techno street festival in Switzerland and, living in Beijing for most of the 2000s, programmed DJ lineups at some of China’s top music festivals, like Modern Sky and Midi. But it was in Taipei of the late-1990s where he really cut his teeth, launching Taiwan’s first raves, Taipei’s first club for electronic music and spreading the beat-driven gospel of rave.

“I’m extremely grateful that when I was young,” Chen wrote in a recent social media post, “I was lucky enough to experience electronic music at its most vibrant, in the 90s when it was creative, idealistic and beautiful.”

Photo courtesy of DJ @llen

Chen, now 59, began DJing while still a student at Taipei’s Fu Jen University in 1988 or 1989 at a time when Taiwan had just ended 38 years of martial law and prohibitions against public dancing.

He started out at a small Shida-area bar called Top, where he played rock and 80s disco to an after hours crowd. He was then hired to the original Roxy by legendary music bar owner Ling Wei (凌威), and then from 1992, in Ling’s new dance club, Spin — a dingy basement with a cranking music system that stayed open till 4 or 5am.

“At Spin we played a lot of dance music, but it wasn’t really electronic music yet,” Chen said.

In addition to rock, hip hop and oldies, they played industrial dance music, EBM [electronic body music] and some acid house.

The records were all owned by the club and kept behind the DJ booth, an arrangement then standard in Taiwan. They were mostly 12-inch dance singles, and their major source was Crossline Records (交叉線唱片行), which made a business of importing records for clubs.

“Even if they didn’t have what we wanted, we would tell them to import it. Sometimes they imported music only for us,” Chen recalled. “For some records, you’d only be able to hear them at Spin, because no other DJs in Taiwan even had them.”

LONDON’S RAVE SCENE

Chen visited London for the first time in 1993 and there immersed himself in techno clubs and warehouse raves.

“That was my first real experience of rave parties,” he said. “I’d never been to a club like that. It was so dark, and there was almost nothing there, just an empty warehouse. But there were tons of people just dancing their heads off.”

“In Spin, we had people dancing really crazy, but they were drunk. This was different. They were all on pills.”

Chen returned to Taipei from London with a suitcase full of records, techno and avant-garde platters by Richie Hawtin and Aphex Twin.

“And now that I’m talking about this, I think I was the first one to play my own records in the clubs. I can’t remember anyone doing that before me.”

Chen also capitalized on an explosion of foreign magazines suddenly available in Taiwan through Eslite Bookstore (誠品書店), which first opened in 1989 and by the early 1990s had become a wellspring for subcultural currents.

“I would buy every issue of the Face, DJ Magazine, MixMag,” Chen said, “even, like, Jockey Slut, which was a British zine. I owned every issue.”

At Spin, the cutting-edge techno records went over like a lead balloon. Chen spun at prime time on Saturday nights, but “when I switched to electronic dance music, I cleared the floor. Ling Wei was really unhappy. He came to me, saying, ‘What are you doing? This is not music. Where’s the guitar? Where’s the people singing? Where’s the lyrics?”

But some were into the new sound. Benjamin Huang (黃超) had gotten into rave culture in the UK and Thailand and invited Chen as his first resident DJ at what would be Taiwan’s first dedicated electronic music club, Twilight Zone. Opened in early 1994, the club was quickly renamed Underground and took a logo modeled on the London subway system. But it only lasted a little more than a year.

Then, suddenly, “I had nowhere to DJ, nowhere to share my music. But a lot of customers from Underground were asking me, ‘Where do we go now?’”

That’s when Chen decided to throw a rave.

THE FIRST RAVE

A location was suggested to him by the editor of a just-launched counterculture tabloid called POTS (破報), which was modeled on New York’s Village Voice. The editor, Huang Sun-chuan (黃孫權), told him about a floodplain in Taipei County which had just a year earlier hosted an experimental noise and art event, the Broken Life Festival (破爛生活節), which even today retains a seminal, cult status among Taiwan’s underground movements.

“What’s good about the site, [Huang] told me, is, because it’s between Taipei City and Taipei County, the police don’t patrol there,” Chen said. “So I thought, yeah, it’s a perfect place.”

That first rave “was very, very simple,” he said. “I brought my own DJ mixer and turntables. We carried everything in a little truck from a glass company that was just downstairs from where I lived.” Lighting consisted of just a couple black lights and a spinning pole from a Taipei barber shop.

In the beginning, the raves were all free parties.

“We only started selling tickets later on when we had to rent the sites, or to pay for bigger sound systems,” Chen said.

As the scene steadily grew, so did Chen’s reputation. In 1996, now as DJ @llen, he put out a CD “Dance No Ecstasy,” its cover an ecstasy pill inside a red circle with a slash through it, “the first DJ mix in Taiwan.” In 1999, he co-authored a book, the first of its kind in Chinese, The Electronic Music Bible (2001電音世代-電子舞曲聖經).

Chen’s first 1,000 person rave hit in 2000 at the Mingde Amusement Park (明德樂園) in the foothills just north of Taipei.

DARK TURN

But the scene was about to take a dark turn.

The party drug MDMA, soon to become known to Taiwan’s media as yaotouwan (搖頭丸), the “head shake pills,” was by then flooding into new warehouse-sized clubs around the island, especially around Taoyuan’s Zhongli District (中壢) and Taoyuan, which drew hundreds or thousands on almost a nightly basis.

It was Taiwan’s first modern trend of recreational drug use, and it exploded into the media in 2002 following a beach rave during that year’s spring holiday. Reporting on the event, a weekly scandal sheet called Next Magazine (壹週刊) ran a cover expose on the beach party with the headline “Thousands at Drugs Sex Party.” Another Kenting rave that same weekend saw police detain 500 partiers for drug use, with more than 100 testing positive.

“That party, it killed everything,” said Chen.

In the early 2000s, the warehouse clubs all shut down and police raids at electronic music events were common. But the genre would outlive the stigma and today is part of the mainstream. Touring EDM parties like S2O and Ultra now draw tens of thousands and are promoted like pop concerts.

Looking back, Chen said, “For me, the few years after 1995 were the most memorable and luminous period of Taiwan’s underground dance scene. In 1997, the club @live opened in Taipei. They invited Paul Oakenfold to play, and that started off a more commercial craze for top 100 DJs. The story after that is history.”

On Saturday, DJ @llen will be joined by DJs Hwa, Sonia Calico, Inn, Sandy’s Trace, Max Huang, Bo Yin, and Brotherbones. At the time of Taiwan’s first rave, some of those DJs weren’t even born yet.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name