Xu Pengcheng looks over his shoulder and, after confirming the coast is clear, helps his crew of urban adventurers climb through the broken window of an abandoned building.

Long popular in the West, urban exploration, or “urbex” for short, sees city-dwelling thrill-seekers explore dilapidated, closed-off buildings and areas — often skirting the law in the process.

And it is growing in popularity in China, where a years-long property sector crisis has left many cities dotted with empty buildings.

Photo: AFP

Xu, a 29-year-old tech worker from the eastern city of Qingdao, has amassed hundreds of thousands of followers for his photos of rundown schools and vacant cinemas. “When people see these images, they find them incredibly fresh and fascinating,” he said.

“The realization that so many abandoned buildings exist — and that they can photograph so beautifully — naturally captures attention.”

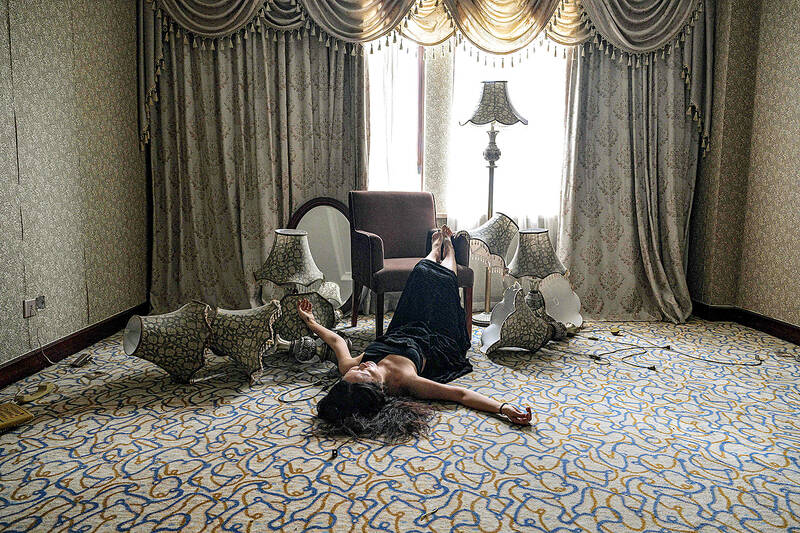

Xu and his comrades arrived on May 24 at a deserted hotel in the outskirts of Shanghai for a unique photoshoot.

Photo: AFP

From the outside, the hotel looked like a prefabricated medieval castle. Once inside, it was clear the property had been abandoned for years. Searching through the rooms for good spots for striking photos, Xu and his friends came across remnants of the hotel’s past — a mahjong table, laundry sheets and piles of dinner plates. Props from past photoshoots were scattered on the floor and on one ballroom wall, “Long Live Chairman Mao” was written in spray paint.

China’s recent property market downturn has left many abandoned large-scale projects ready ground for urban explorers.

“I don’t think you would find sites like this in Europe,” long-time explorer Brin Connal said as he walked around an empty, abandoned building.

Photo: AFP

“In China, there’s a lot of these places which are unfinished.”

SENSE OF COMMUNITY

One such unfinished megaproject in Shanghai, the Pentagon Mall, has become such a hotspot that explorers leave messages for each other on the walls of its top floor.

“I think this is something really special about Chinese urban exploration,” said Sean, a Shanghai resident who did not want to give his real name. “There’s a very strong sense of community and it’s very, very welcoming.”

Situated in Shanghai’s Pudong district, the project came close to completion in 2009 but investment fell through.

The giant concrete building now sits mostly in disrepair — broken tiles litter the ground and a large faded map of the uncompleted mall is barely visible under a thick layer of dust. Some rooms still have signs of life, with mattresses from squatters, discarded takeout and cigarette boxes and even laundry hanging outside.

“In places like Shanghai, people always find a way to make use of these buildings, even if they’re not completely built and completely usable,” said Sean’s exploration partner Nov, who also asked to go by a pseudonym.

WAY TOO DANGEROUS

Chinese social media companies are less enthusiastic. Looking up abandoned buildings on Instagram-like Xiaohongshu, users are met with a message warning “there are risks in this area, please pay attention to safety and comply with local policies and regulations.”

Connal, originally from the UK, said he understood the restrictions. “Some of them are way too dangerous, and some of these abandoned locations were getting overwhelmed with people,” he said.

The hobby also takes place in a legal grey area.

Many urban explorers go by a simple mantra — taking nothing from the places they visit and leaving nothing behind. But the act of trespassing can come with fines in China, just as it does in the West. Xu also acknowledged the risks that come with urban exploration — from angry security guards to errant circuitry.

“Firstly, you might face the risk of trespassing illegally. Secondly, private properties may have security guards or be completely sealed off,” he said. “These locations often involve hazards like no electricity or lighting, structural damage, and injuries from construction materials like exposed nails.” But model Mao Yi said the hobby offered a respite from the drudgery of big city living.

“Living in these sprawling metropolises of steel and concrete, we’ve grown familiar with the routines of daily life,” she said.

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful