If the word “revolution” implies, etymologically, a world turned around, then what unfolded in Russia in 1917 was just that. Everything changed. Old-school deference was dead; the proletariat was in power.

The communist American journalist John Reed was there to witness the contretemps that captured the suddenness of the change.

Reed had the zeal of the convert. Born into a pig-iron fortune in Oregon, he rebelled against his preppy upbringing by embracing the bohemia of Greenwich Village. Thereafter, he was fired up by the silk weavers’ strike in New Jersey in 1913. Four years later, a sense of adventure and a folie a deux with his socialist wife Louise Bryant took them to Saint Petersburg (then Petrograd), where they witnessed the revolution’s great set pieces first-hand.

Warren Beatty’s portrayal of him as a true believer in the biopic Reds, leafleting and dodging bullets, got him down to a tee. So it was hardly surprising that he was faced with sedition charges on his return. He was indicted for violating the Espionage Act for inveighing against US entry into WWI. Hounded out of his homeland, he fled to Russia and died of typhus, aged 32; no medicines were available on account of the Western blockade of the Russian Civil War.

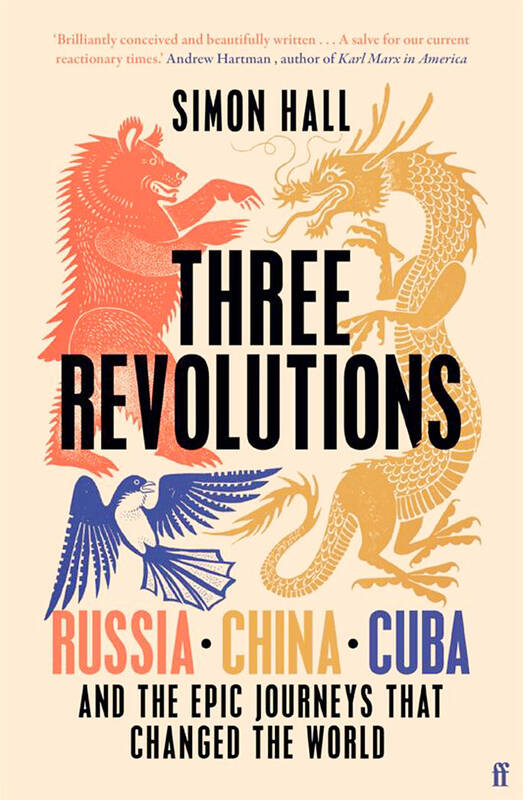

Reed’s is one of six lives served up by historian Simon Hall in his new book. Three of them are revolutionaries — Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong (毛澤東) and Fidel Castro — and three are American journalists who filed stories from the frontlines of the Russian, Chinese and Cuban revolutions, respectively: Reed, Edgar Snow and Herbert Matthews. These are unexpected pairings, chosen, one presumes, for their convenience in enabling Hall to reconstruct his three very foreign societies with the help of a largely monoglot bibliography.

The conceit is to chronicle the journeys that represented turning points in 20th-century history. In Lenin’s case, it was his return to Russia from Swiss exile in April 1917. Something of a party pooper, he maintained that the February Revolution that overthrew the tsar wasn’t the real deal. In good time, his comrades came around, and that’s how we got the Russian Revolution.

In China, meanwhile, the Long March of 1934-5 was a desperate retreat. It was also a lesson in geography and endurance. On the run from the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), who was working with Hitler’s general Hans von Seeckt, some 90,000 troops and persecuted communists made the 9,000-kilometer trek from the Jiangxi Soviet in the south to Yan’an in the north. Only about 6,000 survived, and Mao emerged as their leader.

For his part, Castro returned to Cuba from Mexico in 1956 aboard the Granma, “a creaking, leaking leisure yacht.” As one companero put it, it was not so much a landing as a shipwreck. Not all of them managed to negotiate the mangrove thickets of Playa Las Coloradas and Fulgencio Batista’s strafing planes, but Castro did. Three years later, he toppled the dictator.

Hall’s tired trot through the three coups is less interesting than the three scoops he describes. Besides Reed’s, we have the midwestern ad man turned journalist Edgar Snow’s. He spent four months swimming and playing tennis with Mao’s guerrillas in Bao’an, writing up the experience gushingly in Red Star Over China. Zhou Enlai (周恩來), wrote Snow, was “every inch an intellectual,” Mao a “gaunt, rather Lincolnesque figure,” and the comrades “the freest and happiest Chinese I had known.”

Hall says that Red Star Over China was “no crass work of propaganda.” But it was. Snow would have known about Mao’s purges in the Jiangxi Soviet from 1931-36, in which, it was later revealed, 700,000 people perished.

Herbert Matthews of the New York Times was equally starstruck by his subject. Here he is on Castro, whom he met in the Sierra Maestra mountains in 1957: “This was quite a man — a powerful six-footer, olive-skinned, full-faced with a straggly beard.” What’s more, Castro was “not only not Communist but decidedly anti-Communist.” Matthews’ dispatches went a long way in swaying American opinion against Batista’s dictatorship, but needless to say, some of the more confident pronouncements about Castro’s politics aged badly.

Hall’s potted narratives trundle along, absorbing rich period and cultural details. His strengths lie in storytelling, not history-writing, which is to say he is more at home with description than analysis. But there lies the rub. Unlike Reed, Snow and Matthews, he is writing at one remove. This necessitates extensive quotation and, worse, lengthy paraphrases that are inevitably weaker than the lapidary originals.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an