June 16 to June 22

The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895:

“Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?”

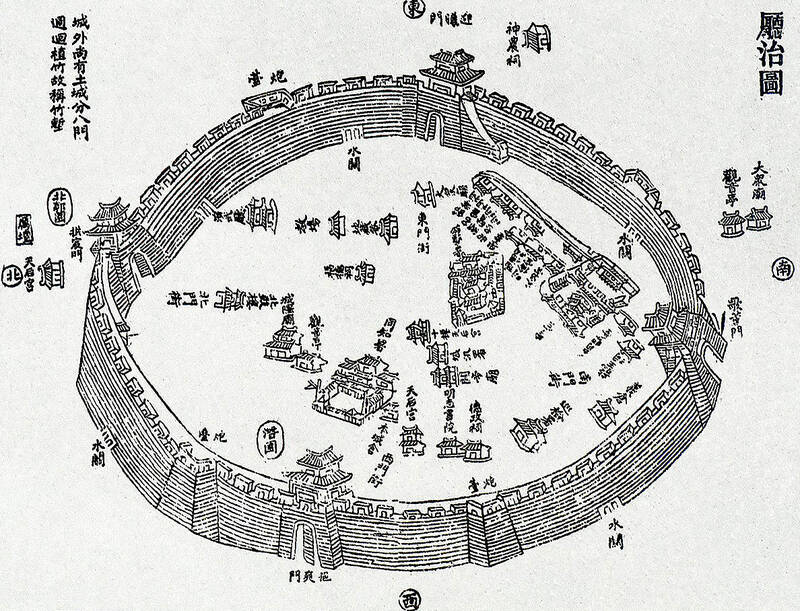

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake Taipei, which the Japanese captured five days earlier without facing any resistance. After setting up their administrative offices in the city, the colonizers set their sights south, the goal being to capture the southern stronghold of Tainan.

By that time, the resisting Republic of Formosa’s president Tang Ching-sung (唐景崧) had fled to China, and the remaining Qing troops seemed more interested in looting, so the Japanese didn’t expect it to be too difficult.

But the Hakkas of Taoyuan, Hsinchu and Miaoli were well-versed in organized warfare — whether it be against other ethnic groups or helping the Qing Dynasty quell unrest as “righteous people” (義民). Various local militias banded together and swore to drive the Japanese out of Taiwan, but they first had to defend their homeland. They found success at first, but eventually succumbed to superior Japanese firepower.

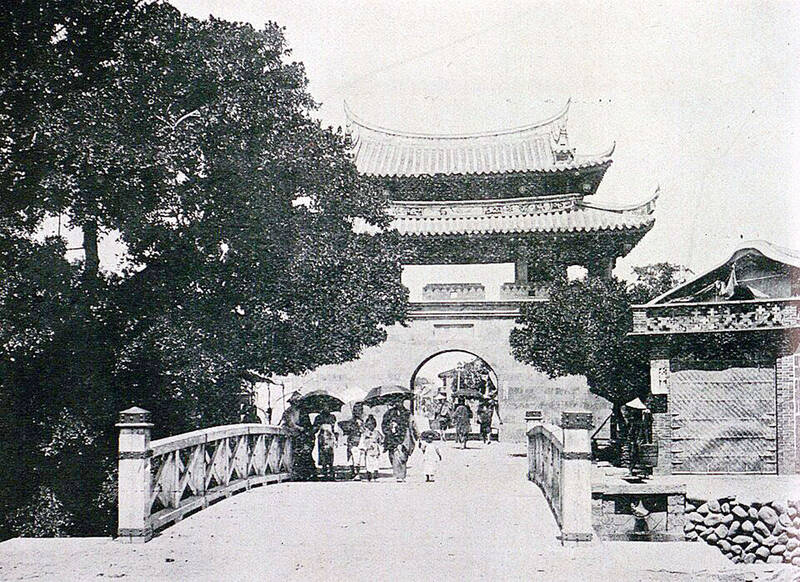

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

However, even after the Japanese entered Hsinchu on June 22, the resistance leaders wouldn’t give up, making several attempts to reclaim the city before retreating further south to regroup.

TIME FOR DUTY

Wu was born to a prominent family in Miaoli’s Tongluo Township (銅鑼) and was a respected local leader. When he heard that Tang and Chiu Feng-chia (丘逢甲), who also hailed from Tongluo, had proclaimed the Republic of Formosa on May 23 to resist the Japanese takeover, he immediately offered his services. Under vice-president Chiu’s recommendation, Tang appointed Wu as the commander of Taiwan’s civilian militias.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Japanese landed in Taiwan on May 29, and Tang escaped to China before they reached Taipei, having served as president for less than two weeks. Chiu eventually followed Tang’s footsteps, and although the exact date of his departure is disputed, his name doesn’t appear in any records involving resistance efforts south of Taipei (see “Taiwan in Time: Patriotic poet or embezzling deserter?” Dec. 23, 2018).

Two days after the fall of Taipei, Wu arrived in Hsinchu with about 700 fighters, with countless more volunteers and other militias joining their ranks there over the next several days, writes historian Lin Cheng-hui (林正慧) in “The Hakka during the Japanese invasion of Taiwan in 1895 ” (1895 年乙未之役中的臺灣客家). Sources show that their numbers exceeded 10,000, and included notable civilian militia leaders Chiang Shao-tzu (姜紹祖) from Beipu (北埔), Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) from Toufen (頭份) and Hu Chia-yu (胡嘉猷) from Pingzhen (平鎮).

Joining them were Chiu Feng-chia’s former forces led by Chiu Kuo-lin (邱國霖) and Wu Chen-kuang (吳鎮洸), and Lin Chao-tung’s (林朝棟) battle-tested “Taiwanese braves” (see “Taiwan in Time: From village strongman to imperial commander,” May 15, 2022), now under the command of Hsieh Tien-te (謝天德) and Fu Te-sheng (傅德生). After bringing his family to safety in China, Lin returned to Taiwan in June to join the fight — but upon seeing that Taipei had already fallen and the Japanese were already in Taoyuan, he changed his mind and headed back across the Taiwan Strait.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On June 11, Wu was officially sworn in as the resistance leader in Hsinchu, changing scholarly robes for military garb. They put up flags and raised a large drum, telling volunteers from each village to gather upon hearing it. Wu set his gaze north and pronounced, “It’s time for us to serve our duty! Let’s rise!”

INITIAL SUCCESS

They first encountered the Qing braves (irregular troops) fleeing south after the fall of Taipei. Upon hearing that they gave up Taipei without a fight and were looting villages, local fighters vanquished them before they could reach Hsinchu, Lin writes.

The main Japanese force met little resistance from Taipei to Jhongli, but once it crossed the Touchong River in today’s Yangmei District (楊梅) on June 14, things changed. Instead of the usual white flags, they saw anti-Japanese flyers posted on the streets. The houses were all empty with the doors bolted shut.

Wu established defense lines in Yangmei and Hukou (湖口), and the militias sent troops north to engage with the Japanese who had just passed Jhongli. They gained the clear upper hand, but a Japanese warship passing by the coast fired dozens of cannon shots, causing the fighters to pause — and the Japanese took the chance to escape.

Wu’s troops clashed with the Japanese in Hukou the same day, forcing them to retreat to Jhongli and Taoyuan after three days of battle. These events greatly boosted morale. During this same time, locals also launched successful attacks at Sansia (三峽) and Longtan (龍潭).

Frustrated, the Japanese put together an army of more than 1,000 led by colonel Shigeki Sakai, setting out from Taipei on June 19. Despite suffering much damage in Pingzhen, Hukou and Yangmei, Sakai’s soldiers managed to surround Hsinchu with artillery support, entering the East Gate on June 22.

LIBERATION ATTEMPTS

Wu retreated to Miaoli to reorganize his troops. This effort was aided by Miaoli governor Lee Chuan (李烇), who provided the fighters with money and military supplies under orders from Taiwan Prefecture governor Lee Ching-sung (黎景嵩). Meanwhile, Hsu joined with militias from Pingzhen, Longtan and Guanxi to disrupt Japanese communications between Taipei and Hsinchu.

The mission to liberate Hsinchu began on June 25. Wu and Chiu charged toward the city from the southwest, Huang Nan-chiu (黃南球) from the south and Chiang and Fu from the north and west. However, they were repeatedly repelled by Japanese cannons.

Despite the setback, resistance continued to spread in the area, and the Japanese suffered more losses in Pingzhen and Sansia. Even the initially neutral township of Dasi (大溪) joined the fray, and the Taichung-based Lee Ching-sung sent his New Chu Army north to help. Together, they continued to fight the Japanese and disrupt their operations over the next two weeks, with neither side gaining the upper hand.

On July 9, the resistance launched another multi-pronged attack on Hsinchu. They were joined by numerous other militias, but the Japanese drove them off once more. Chiang was taken hostage, and he reportedy committed suicide by ingesting raw opium.

While Wu continued to launch sporadic attacks at Hsinchu, the militias from areas north of the city continued to defend their respective hometowns with moderate success. Those in Sansia feigned loyalty to the Japanese then ambushed them along with the Daxi militia, causing severe losses.

The Japanese finally had enough, and launched two brutal punitive campaigns on July 18 and July 28. By burning down houses and indiscriminately killing civilians, they finally stamped out local resistance in the area.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

As devices from toys to cars get smarter, gadget makers are grappling with a shortage of memory needed for them to work. Dwindling supplies and soaring costs of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) that provides space for computers, smartphones and game consoles to run applications or multitask was a hot topic behind the scenes at the annual gadget extravaganza in Las Vegas. Once cheap and plentiful, DRAM — along with memory chips to simply store data — are in short supply because of the demand spikes from AI in everything from data centers to wearable devices. Samsung Electronics last week put out word