With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation.

Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead.

Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century.

Photo: Bonnie White

Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty.

“People are influenced by fantasies, but [Bourgeois’] work is raw,” says co-curator Reiko Tsubaki.

Raised in her family’s tapestry restoration workshop, Bourgeois developed early craftsmanship. From marble to wood, steel to gouache, her skills became her language.

Photo: Bonnie White

The show unfolds in three main sections — motherhood, emotional struggle and reconciliation, reflecting Bourgeois’ lifelong engagement with family trauma, plus two columns showcasing some of her early works.

Adding a local touch, famous Taiwanese pop singer Stella Chang (張清芳) narrates the Chinese version of the audio guide.

MOTHER

Photo: Bonnie White

The opening chapter, “Do Not Abandon Me,” unravels Bourgeois’ relationship with motherhood.

The centrepiece Breast and the Blade (1991) captivates. From one angle, tender breasts cast in bronze are exposed; from another, a blade sticks out, guarding the socle.

In the corner, Nature Study (1984), a pink headless dog with six breasts, stands watch. The grotesque and maternal figure evokes unease and guardianship.

To Bourgeois, motherhood was both a burden and a source of creation. Her sculptures express the female body as a site of contradiction: nurturing yet wounded, exposed yet defiant.

The spider, a recurring motif in her work, is another metaphor: the fierce protector mending broken webs.

“My best friend was my mother, and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat and as useful as an araignee,” Bourgeois said in a 1995 interview.

FATHER

In the second chapter of the exhibition, “I’ve been to hell and back,” the exhibition turns inwards.

The space shrinks in the dim-lit room, echoing the claustrophobia of memory and rage.

Cages and erotic images overwhelm the viewer. The room exudes psychic pain and fractured bodies.

While her mother suffered from chronic illness, young Bourgeois endured her father’s decade-long affair with their house governess. This painful memory became a driving force in her art, allowing her to externalize her anger and unresolved grief.

“Making art became an outlet for Bourgeois to deal with pain,” co-curator Manabu Yahagi says.

The Destruction of the Father (1974) bathed in red light is embedded into the wall like a wound. Inside, gnawed flesh forms on a dinner table, luring visitors into Bourgeois’ childhood revenge fantasy of devouring her father.

RECONCIALIATION

Moving across to the last chapter, “Repairs in the Sky,” the mood shifts. Bourgeois’ fabric works from the restorative phase of her practice decorate the walls.

These pieces, made from salvaged household fabrics and objects once belonging to family members, embody her desire to physically mend the past.

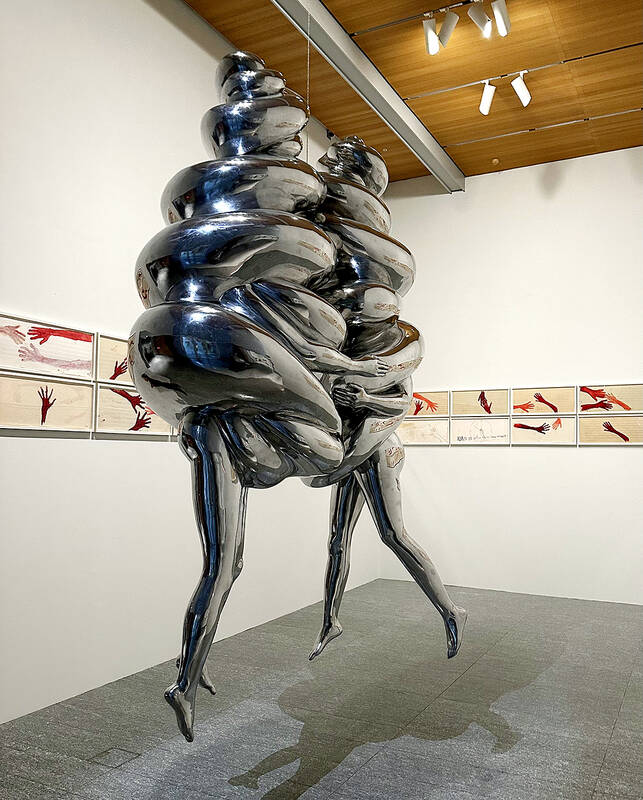

Towering 15 feet, Spider (1997), from Bourgeois’ “Cell” series, anchors the room. The monumental bronze legs encase a cell adorned with tapestry scraps, symbolizing both maternal protection and the entrapment of memory.

Upstairs, the final section of the exhibition opens into a vast room. Bourgeois’ later works invite reflection and healing.

Under a bright skylight, Arch of Hysteria (1993), a suspended bronze figure, arched in tension and release, captures the raw physicality of emotional suffering.

Across the room, gentle shades of blue wash over the sparse room, concluding Bourgeois’ psychoanalytic journey.

“I see her as one of the most incredible craftswomen, and the younger generation can learn much from her,” Manabu Yahagi says.

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government

Nov. 3 to Nov. 9 In 1925, 18-year-old Huang Chin-chuan (黃金川) penned the following words: “When will the day of women’s equal rights arrive, so that my talents won’t drift away in the eastern stream?” These were the closing lines to her poem “Female Student” (女學生), which expressed her unwillingness to be confined to traditional female roles and her desire to study and explore the world. Born to a wealthy family on Nov. 5, 1907, Huang was able to study in Japan — a rare privilege for women in her time — and even made a name for herself in the