June 23 to June 29

After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month.

Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

“We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages and hindering our troops,” telegraphed governor-general Sukenori Kabayama to prime minister Hirobumi Ito.

Last week’s column (“Taiwan in Time: The Hakka defenders of Hsinchu,” June 15, page 12) explored how Hakka militias in Sansia (三峽), Taoyuan and Hsinchu refused to submit to Taiwan’s new overlords, even driving them back north several times. However, the Japanese prevailed with superior firepower.

By the end of July, major general Nobunari Yamane had finished clearing out the resistance north of Hsinchu, resorting to scorched-earth tactics to terrorize locals into submission. The various army brigades, including reinforcements from Japan, amassed in the walled city, and on Aug. 2, Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa arrived to assume command.

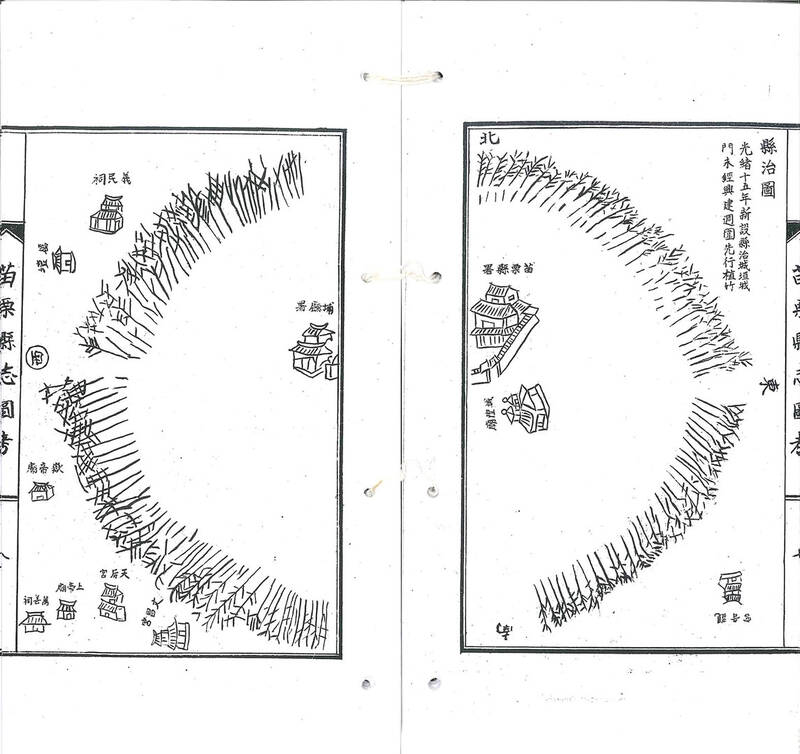

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

Meanwhile, the Hakka militias led by Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興) regrouped in the Jianbishan (尖筆山) mountains in today’s Jhunan (竹南), Miaoli County, their ranks bolstered by New Chu Army members sent from Changhua and Black Flag Army fighters from Tainan.

On Aug. 7, three Japanese brigades marched toward the mountains — and the final showdown of the north was about to begin.

REGROUPING FOR BATTLE

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

By the time they captured Hsinchu, the Japanese were well aware of the tenacity of the Hakka, describing them in detail in various reports and noting that even women and children participated in battle. They superficially resembled the “Qing people,” but were not the same, a newspaper article stated.

Wu reorganized the Hakka troops into five battalions, each guarding a strategic position to the east and south of the city, all the way to Miaoli, writes historian Lin Cheng-hui (林正慧) in “The Hakka Group during the Japanese Invasion of Taiwan in 1895” (1895年乙未之役中的臺灣客家). He also noted that there were tens of thousands of civilians willing to defend their homeland when the enemy showed up.

Wu then asked Taiwan Prefecture (roughly today’s Taichung) governor Lee Ching-sung (黎景嵩) to send him more reinforcements to be deployed to other towns.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

However, internal conflict soon arose between Wu and Miaoli governor Lee Chuan (李烇) over funding for troop wages. Both complained to Lee Ching-sung, who was unable to resolve the issue, and neither could the Miaoli elites. Finally, they turned to Liu Yung-fu (劉永福), who was stationed in Tainan and had assumed command of the Republic of Formosa after its president and vice-president fled to China.

Liu agreed to send Black Flag Army commander Wu Peng-nian (吳彭年) north to investigate the matter, bringing his deputy Lee Wei-yi (李惟義) and hundreds of soldiers with them. They reached Lee Ching-sung in Changhua on July 19, who ended up sending Lee Wei-yi and 300 (some sources say 700) Black Flags to Miaoli’s Toufen (頭份) to join Yang Zai-yun (楊載雲) and the New Chu Army.

After one last attempt to drive the Japanese out of Hsinchu on July 23, Wu Tang-hsing and the resistance retreated to Jianbishan, which served as a natural defense barrier. There, they constructed hundreds of forts over an 8km stretch and braced for Japanese arrival.

CLASH IN THE MOUNTAINS

On Aug. 6, two Japanese brigades, including one led by Yamane, set out from Hsinchu to engage with the resistance to the east. They managed to clear them out in a day, and waited for further orders, writes Wu Chao-ying (吳昭英) in “A Study of the Hakka Resistance in Taoyuan-Hsinchu-Miaoli against Japan in the War of 1895” (乙未戰役中桃竹苗客家人抗日運動之研究).

The next day, two more brigades headed toward Jhentoushan (枕頭山) and Jiluanmian (雞卵面) mountains located between Hsinchu and Jianbishan, clashing there with Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) and Wu Tang-hsing. The resistance fighters were routed and retreated to Jianbishan, which was defended by Chang Chao-lin (張兆麟) and Chiu Kuo-lin (丘國霖). Meanwhile, Yamane’s brigade headed directly toward Jianbishan.

On Aug. 9, the Japanese attacked Jianbishan and Toufen at the same time, supported by two or three warships along the coast firing cannons that shook the hills. They successfully drove the militias from Jianbishan, destroying the forts and burning houses along the way. Meanwhile, Yang and Lee Wei-yi defended Toufen, but Yang was killed and the army scattered. Both sides reportedly suffered significant losses.

By this time, Wu Peng-nian had arrived in Miaoli, but he only had about 300 troops with him and there was no time to recruit more as the Japanese did not slow their advance, writes Hsueh Yun-feng (薛雲峰) in “The Historical Standpoint of the Taiwan Hakka: The Case of the Yi-Ming and the Yi-Wei War of 1895” (臺灣客家史觀: 以義民與1895乙未抗日戰爭為例).

On Aug. 13, the Japanese launched a three-pronged attack on Miaoli City with Prince Yoshihisa personally leading the charge. As a relatively new county seat, it had little defense infrastructure. Wu Peng-nian, Wu Tang-hsing and Hsu Hsiang squared off with the enemy in today’s Houlong (後龍), but their battle-weary troops couldn’t put up much of a fight.

TAICHUNG FALLS

The battles in Jianbishan and Miaoli were an unprecedented collaboration between the various Hakka militias, especially as the Hakka led the charge while the Black Flags and the New Chu Army served as support, Hsueh writes. From then on, the situation was reversed.

When the Japanese entered Miaoli, they saw that most of the people had taken their possessions and sought refuge in the mountains; only about 10 households remained, Lin writes. Lee Chuan had fled to China, while the resistance retreated to Taichung. Morale was low, although Liu Yung-fu promised to send support.

The Japanese rested in Miaoli for nine days then continued pushing south. On Aug. 24, they crossed the Dajia River (大甲溪) and overran Taichung despite continued resistance. The only remaining defense position in central Taiwan was Baguashan (八卦山) in Changhua, and the fighters met with other militias, Black Flags and remaining government troops there for what would be the largest clash between the two sides (see Taiwan in Time: Defending the homeland to the death, Aug. 28, 2016, page 8).

Wu Tang-hsing and Wu Peng-nian both died in the ensuing battle, while Lee Ching-sung fled to China. The surviving Hakka fighters followed Hsu Hsiang to Tainan, still refusing to give up.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful