April 7 to April 13

After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net.

He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving them for three months before enduring a grueling land journey to Guangzhou.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

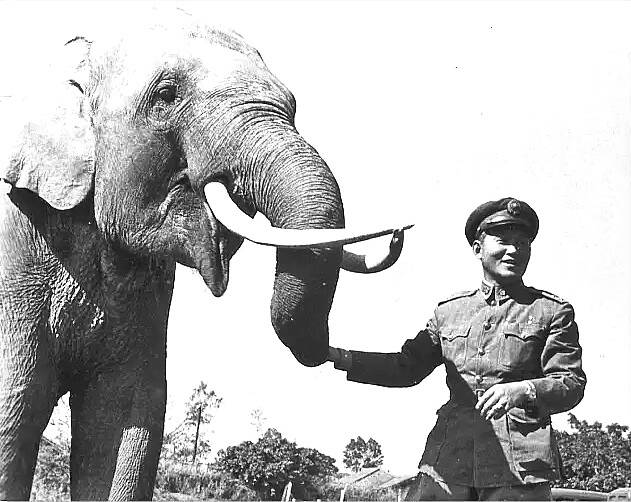

Of the original group of 13 elephants, six died and four were sent to zoos across China; these last three would accompany General Sun Li-jen (孫立人), commander of the New 1st Army, to his new post in charge of the Army Training Command in Kaohsiung.

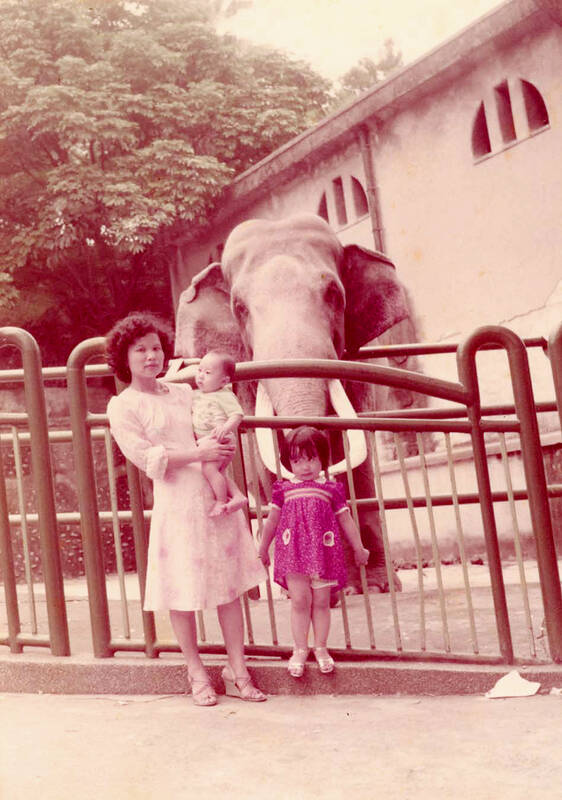

A-Lan died shortly after arrival and A-Pei several years later. The lonely A-Mei was sent to the Taipei Zoo in Yuanshan in 1954 to “marry” Ma Lan (馬蘭), a young calve that was the facility’s only elephant.

The zoo renamed A-Mei “Lin Wang” (林王), meaning “king of the jungle,” but the media misprinted it as “Lin Wang” (林旺), probably because it was a common given name at the time for males. This mistake stuck.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lin Wang soon became the zoo’s main attraction, and as he entered his 60s, was affectionately known by children as “Grandpa Lin Wang.” In 1986, the itinerant elephant was moved for one last time — to the current Taipei Zoo in Muzha (木柵). Nearing 70 years old, Lin Wang refused to be loaded, requiring a gargantuan effort that was widely covered by the press.

ELEPHANTS AT WAR

Author Yin Chun (尹駿) was part of the brigade that seized Lin Wang from the Japanese, detailing the experience in his 1993 book, Lin Wang’s Story (林旺的故事).

Photo courtesy of Picyrl

Yin was part of the New First Army led by Sun, sent to help the Allies clear out Japanese forces in Myanmar during World War II. His 30th Division was tasked with capturing the town of Namhkam in January 1945, but their advance was stopped by the roaring Ruili River.

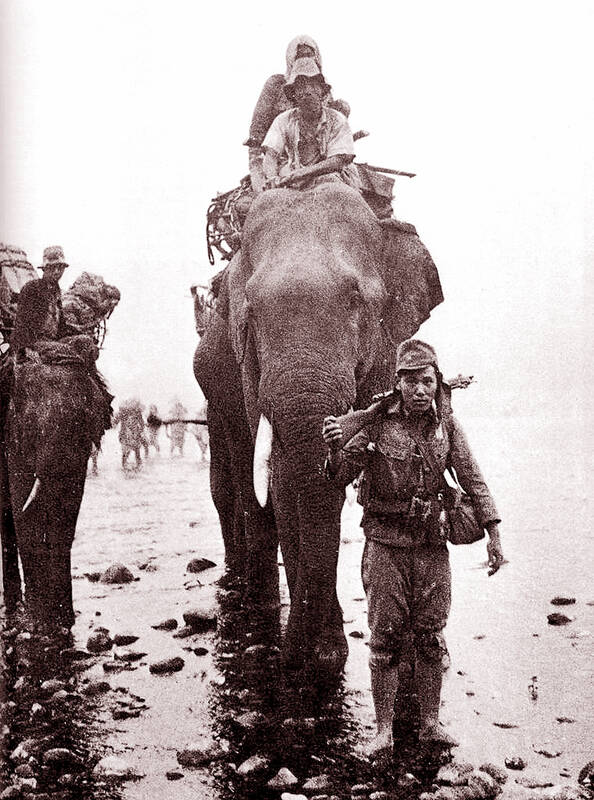

Having learned about the war elephants from a Japanese prisoner, division leader Tang Shou-chih (唐守治) thought they could have the elephants stand in formation across the river with planks linking them together to form a bridge. Yin and four other men disguised themselves as Burmese civilians and ventured toward the Japanese base across the river, finally finding 13 elephants in a bamboo forest with ammunition and supplies on their backs.

They told the Burmese keepers that the Japanese commanded them to send these elephants to the frontlines, but the keepers soon realized something was wrong and fled. The troops then managed to herd the elephants across the river and delivered them to the army. Lin Wang was the youngest and the fittest, estimated to be in his late 20s.

Photo courtesy of New Taipei City Cultural Affairs Department

The bridge plan failed as the currents were so strong the elephants couldn’t stand still, but the army made it across anyway and successfully drove the Japanese out of Namhkam. The elephants were the center of attention at the victory press conference, and their photo was sent across the world.

GETTING ‘MARRIED’

The pachyderms joined the army’s transport team, and the soldiers were reportedly quite fond of them — especially A-Mei. Three months later, they were ordered to return to China; only seven elephants survived the brutal journey. They continued to perform labor in Guangdong and put on shows for spectators until Sun decided to bring them with him to Taiwan.

A-pei had long been considered Lin Wang’s first “wife,” but during an exhibition in 2018, experts determined that he was male, just smaller with less prominent tusks. He died in 1951, and afterward Lin Wang began showing signs of depression.

A year later, four-year-old Ma Lan arrived at the Taipei Zoo from Thailand, replacing Maa-chan, who died in 1950 after spending 24 years in Taiwan. In 1954, the zoo decided to pair Lin Wang with Ma Lan, and then-Taipei mayor Wu San-lien (吳三連) personally visited Sun to “propose the marriage.” The “wedding party” of trainers and technicians then traveled south and loaded Lin Wang onto a 14-wheeler on Oct. 28, arriving in Taipei two and a half days later.

The problem was that Ma Lan had not reached sexual maturity yet, and by the time she did, Lin Wang was too old to mate; so the pair never had any offspring. The two did have their spats, and Lin Wang chased Ma Lan out of their enclosure into a ditch several times. But they generally got along.

When Ma Lan died in 2002, an agitated Lin Wang repeatedly rammed the enclosure gate and bellowed in grief.

SENIOR RESIDENT

At first, Lin Wang was free to roam his enclosure, but every year he would enter his “musth” period when his testosterone levels multiplied along with his aggression. The zoo shackled one of his legs to prevent him from rampaging, but he began showing typical swaying behavior of tethered elephants, at times using his trunk to unscrew the shackles. In 1977, the zoo built another enclosure to isolate him when needed, finally removing his chains.

Lin Wang remained affable to humans until 1967, when doctors found a tumor in his rectum. They did not have the experience or equipment to properly anesthetize him, so they forcefully tied him up and carried out the surgery. His attitude completely changed from then on, only allowing a few trusted zookeepers to approach him.

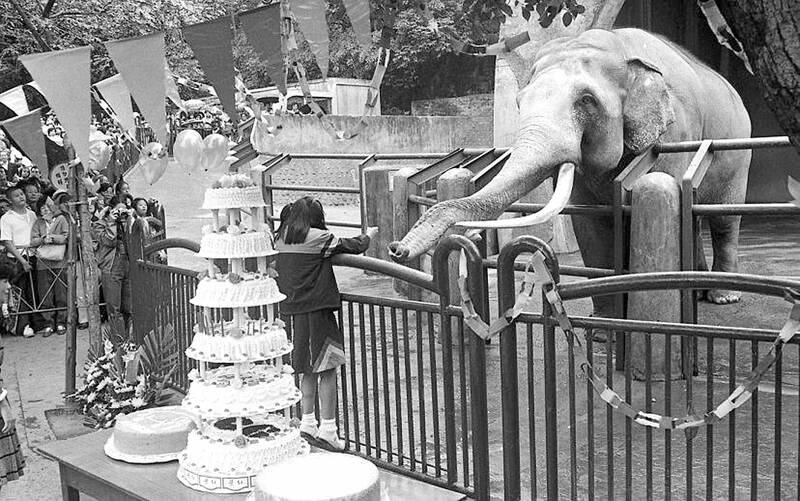

In 1983, the zoo held a 66th birthday celebration for Lin Wang as it was an auspicious number, attracting countless visitors. The media interviewed former members of the New First Army and for the first time, Lin Wang’s former life as a war elephant became known to the public. They celebrated his birthday yearly from then on as a major zoo event.

When it came time in 1986 for the animals to move 20km to the new zoo in Muzha, many citizens worried that the aging Lin Wang would not be able to withstand the journey. But the decision had been made. Three months before the move, the zoo placed two shipping containers in the enclosure and put their daily meals inside, hoping to acclimate them.

Lin Wang entered the container immediately on the big day, but ran out before the staff could close the door. When lured by food, he used his trunk to grab the food while blocking the door with his hind legs. It took more than a dozen zookeepers two hours to push him inside, breaking two ropes that they were using to control him. Ma Lan was also resistant, and by the time they finally got moving, it was already dusk.

It was dark when Lin Wang was released from the container. In his confused state, he mistook an elephant-shaped phone booth for Ma Lan, rushing toward it and falling into a ditch. He refused to leave the ditch until Ma Lan was let out of her container; he ran toward her and they embraced each other. Their new residence was dubbed the “White House” due to its color.

Lin Wang fell ill soon after Ma Lan died, passing a year later at the age of 86 in February 2003. He remains the oldest Asian elephant in captivity.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Snoop Dogg arrived at Intuit Dome hours before tipoff, long before most fans filled the arena and even before some players. Dressed in a gray suit and black turtleneck, a diamond-encrusted Peacock pendant resting on his chest and purple Chuck Taylor sneakers with gold laces nodding to his lifelong Los Angeles Lakers allegiance, Snoop didn’t rush. He didn’t posture. He waited for his moment to shine as an NBA analyst alongside Reggie Miller and Terry Gannon for Peacock’s recent Golden State Warriors at Los Angeles Clippers broadcast during the second half. With an AP reporter trailing him through the arena for an