Feb. 17 to Feb. 23

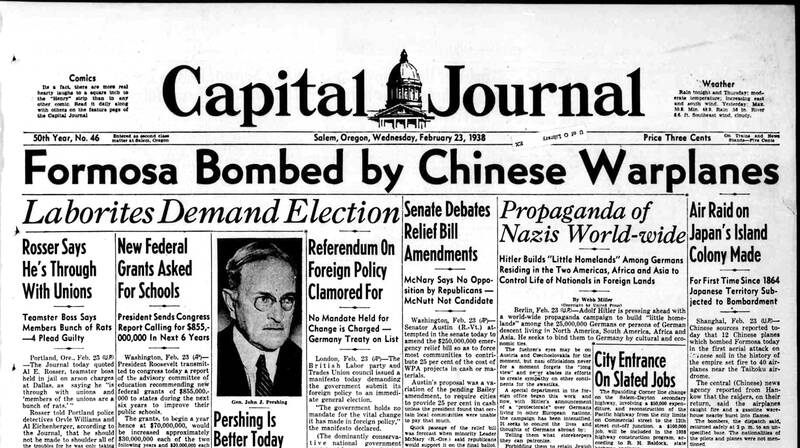

“Japanese city is bombed,” screamed the banner in bold capital letters spanning the front page of the US daily New Castle News on Feb. 24, 1938. This was big news across the globe, as Japan had not been bombarded since Western forces attacked Shimonoseki in 1864.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Numerous Japanese citizens were killed and injured today when eight Chinese planes bombed Taihoku, capital of Formosa, and other nearby cities in the first Chinese air raid anywhere in the Japanese empire,” the subhead clarified.

The target was the Matsuyama Airfield (today’s Songshan Airport in Taipei), which the Japanese had been using to support its full-scale invasion of China, which began on July 7, 1937.

Outlets across the US and China lauded the surprise operation as a success, destroying 40 Japanese warplanes and devastating military infrastructure: “Our air force undertakes long-range overseas mission, fiercely bombs enemy airport in Taipei,” the Southeastern Daily (東南日報) noted. “Our forces completely destroy enemy’s air force base,” the Zhongshan Daily (中山日報) proclaimed.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報), however, reported that the attackers missed their targets and hit residential areas in Taipei and Hsinchu instead, killing a number of civilians. A few days later, the paper claimed that the pilots were Americans and Soviets operating Chinese planes; no Chinese personnel were involved.

Other sources also suggest Soviet involvement. The Canberra Times wrote that it “was suggested that Russian planes were used,” and the Wanganui Chronicle stated the “Times’ Shanghai correspondent says that the Chinese air raid on Formosa was carried out by 12 Russian planes.”

So who did it? And did the mission actually succeed?

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SOVIET ‘VOLUNTEERS’

Since China had no chance of defeating Japan without foreign assistance, it actively sought Western support — but to no avail, especially with tensions rising in Europe, writes Shih Chao-wei (施詔偉) in “Sino-Soviet military relations in the early phase of Sino-Japanese War, 1937-1941” (抗戰前期中蘇軍事關係, 1937-1941).

But the Soviet Union and the Japanese had competing interests in the Far East, especially after Japan invaded Manchuria in 1932 and established the puppet state of Manchukuo. The Soviets resumed relations with China shortly after, but it wasn’t until after the Second Sino-Japanese War officially broke out that the two sides signed the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact on Aug. 21, 1937.

Photo courtesy of University of Oregon Libraries

Soon, the Soviets agreed to supply aircraft to the Chinese and also send pilots and technicians to help with the war effort. For the Soviets, this was a chance for their personnel to gain battle experience and also test the capabilities of Japanese planes.

The mission, top secret because the Soviet Union and Japan were not at war, meant that the soldiers did not know where they were going until the last minute. The first batch of 230 so-called “volunteers” arrived in China by the end of October and formed the Soviet Volunteer Group. They were sent into battle almost immediately, wearing Chinese uniforms with their planes marked with Republic of China (ROC) Air Force insignias.

DARING MISSION

Completed in 1936, the Songshan Airfield was an important launch pad for Japanese operations against China due to Taiwan’s strategic location. On Aug. 14, 1937, 18 Mitsubishi G3M bombers set out from Taipei to destroy the Jianqiao Airbase in Hangzhou. They were soundly defeated by the ROC forces, and since the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the victory is today celebrated as Air Force Day.

According to the article “Red Riposte: the Soviet Volunteer Group Over Formosa” by Alexis Luks and based on first-hand Russian sources, the Chinese learned in February 1938 that the Japanese were assembling a new fleet of fighters at the Songshan Airfield. They turned to the Soviet volunteers, who chose Feb. 23, the 20th anniversary of Red Army Day, to carry out the mission.

The Soviet squadron set out from Hankou, more than 1,000km from Taipei and barely within the range of their speedy Tupolev SB bombers. Twenty-eight planes led by captain Fyodor Polynin took off at dawn, flying at dangerously low-oxygen 5,000m altitudes to save fuel and avoid detection. They reached Taipei several hours later and broke through an opening in the clouds; to their surprise, there were no enemy planes flying nor did the anti-aircraft artillery go off. They then dropped a total of 280 bombs on the base, destroying 40 planes, hangars and fuel tanks before retreating to Fuzhou.

Shih writes that a mixed Chinese-Soviet squadron was supposed to accompany them from Nanchang, but they got lost and never made it to Taipei. The pilots received a hero’s welcome back in China, and the next day First Lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡) hosted a victory banquet for them — an event backed up by other Russian sources.

It should be noted that this account isn’t entirely reliable. It claims, for example, that the governor-general of Taiwan was recalled for this mishap, but that didn’t happened. It also does not account for the damage in Hsinchu.

CONTRASTING REPORTS

Tu Cheng-yu writes (杜正宇) in “Bombing Campaign on Formosa during World War II (論二戰時期的臺灣大空襲) for Bulletin of Academia Historia (國史館館刊) that most reports attributed the mission solely to Chinese fighters because Soviet involvement was still a secret.

The actual damage caused differs greatly depending on the source. Chinese reports at that time match that of the Russian account that the bombs destroyed 40 planes, leaving the airfield in flames and completely disabling its capabilities. They make no mention of Hsinchu, noting that the fighters headed back as soon as the airbase was destroyed.

The Japanese colonial government claimed the opposite. The Taiwan Daily News notes that the fighters dropped 10 bombs at an overly high altitude to avoid anti-aircraft artillery, missing the target entirely. An hour later, they dropped 10 more bombs in Hsinchu’s Jhudong Township (竹東). All the victims were civilians, mostly women and children. Most sources agree that around 10 people were killed, and between 20 to 30 were injured.

Historian Chang Cheng-chiu (張建俅) writes in “War damage of Taiwan during World War II” (二次大戰臺灣遭受戰害之研究) that while the actual damage of the Soviet assault was never fully revealed, “it’s commonly believed that the results were limited, at best it showed the Japanese that the Chinese Air Force had the capability to launch overseas assaults.”

Chang adds that the Japanese authorities downplayed the attack, and it barely caused a stir in Taiwanese society.

George Kerr, who was later a US naval attache in Taiwan, was in Taipei during the attack, and briefly detailed the events in Formosa: Licensed Revolution and the Home Rule Movement, although he incorrectly wrote the date as Feb. 18. Tensions were high in Taipei after a “brief series of shattering explosions shook the air,” with military activity all over the city, but everything had returned to normal the following day.

“A brief official statement said only that on the preceding day a Chinese Nationalist plane “piloted by Russians” had dropped a stick of bombs near the [Songshan] Airfield, and that it was driven back across the strait as it attempted to bomb the Hsinchu refinery, without success.”

It was a “minor affair, a few Formosans killed or wounded and a few houses smashed,” Kerr writes.

Kerr and other foreigners did not believe that it was the Russians, dismissing the detail as a “face-saving gesture: no Japanese officer could admit that a Chinese pilot had penetrated Formosa’s defenses without warning.”

Only later did he find out that it was true.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality