With raging waters moving as fast as 3 meters per second, it’s said that the Roaring Gate Channel (吼門水道) evokes the sound of a thousand troop-bound horses galloping.

Situated between Penghu’s Xiyu (西嶼) and Baisha (白沙) islands, early inhabitants ranked the channel as the second most perilous waterway in the archipelago; the top was the seas around the shoals to the far north. The Roaring Gate also concealed sunken reefs, and was especially nasty when the northeasterly winds blew during the autumn and winter months.

Ships heading to the archipelago’s main settlement of Magong (馬公) had to go around the west side of Xiyu due to the unfriendly seas, making it an important pit stop for fishermen and settlers arriving from China’s Fujian Province. They would dock at the southwestern tip, pray to the deities Guanyin and Matsu and ask about the ocean conditions before disembarking.

Photo courtesy of Academia Historica

The Roaring Gate was mentioned as early as 1685 in the Taiwan Province Annals (台灣府誌): “the waters are turbulent, and ships seldom pass through.” However, two years earlier, when Qing Dynasty general Shih Lang (施琅) routed the Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning’s (東寧) navy in Penghu, losing commander Liu Kuo-hsuan (劉國軒) managed to escape back to Taiwan through the channel.

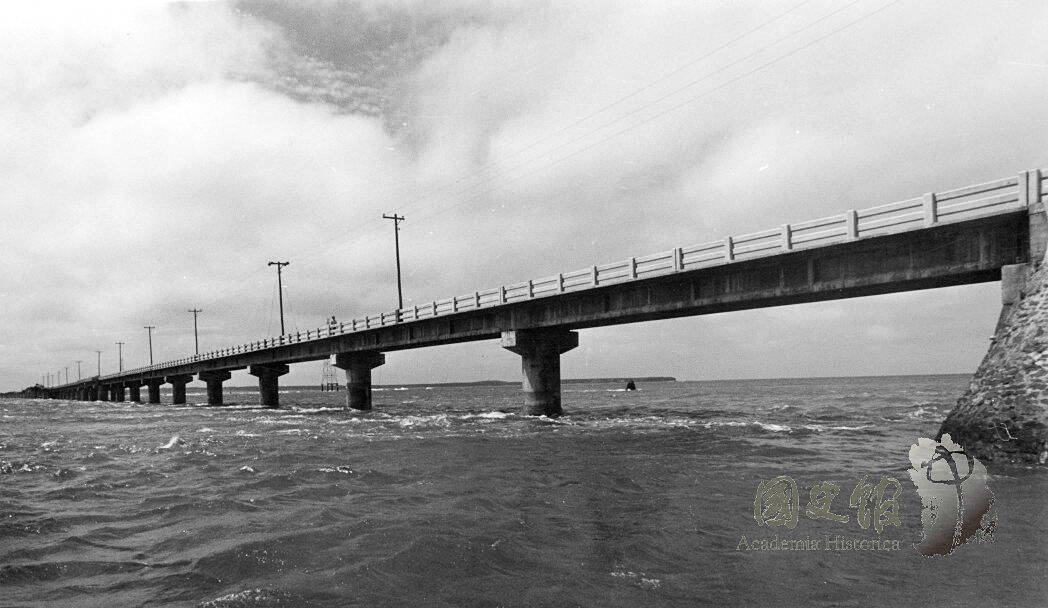

Until 1970, transportation to and from Xiyu relied solely on public and private ferries. This changed with the completion of the Penghu Great Bridge (澎湖跨海大橋) on Dec. 25 of that year, which was at that time the longest bridge in East Asia. This facilitated Xiyu’s rise as a tourist hotspot, but also led to serious rural flight.

The bridge quickly succumbed to the rough elements and heavy traffic. A new bridge was completed in 1996, but the foundations of the original structure can still be seen alongside it.

Photo courtesy of Academia Sinica

DANGEROUS SEAS

According to the Xiyu Township Annals (西嶼鄉誌), the Penghu archipelago was a hotbed for pirates and smugglers during the Ming Dynasty, and the empire in 1388 abandoned the islands, demolishing the infrastructure and institutions they set up and relocating the residents to Fujian Province.

Over the ensuing two centuries, fishermen visited Xiyu seasonally, but never stayed for too long. In 1595, the governor of Fujian allowed people to settle in Penghu again, and records show that the Chen (陳) family from Zhangzhou (漳州) put down roots in Xiyu shortly after.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Between 1625 and 1631, two serious famines devastated Fujian, causing scores of refugees to flee abroad, many from Kinmen landed in Xiyu. The ensuing unrest caused by the Manchu invasion of China and Koxinga’s (鄭成功) attempt to restore the Ming Dynasty led to increased immigration over the next century, still mostly from Kinmen. In 1660, Koxinga defeated the pirates for good and drove them from the archipelago.

Xiyu had long been a navigation reference point for those heading to Penghu from Fujian, its “dark silhouette resembling a bamboo stick” visible from afar,” states the Taiwan Province Annals.”

Shipwrecks were common, with an especially severe incident happening in 1765. In 1778, new Taiwan governor Chiang Yuan-shu (蔣元樞) ordered the erection of a granite tower with an oil lamp on top on the southwestern tip of the island, next to a shrine dedicated to those who perished at sea. This is considered Taiwan’s first lighthouse. In 1823, the lamp was upgraded into a glass lantern with much stronger projection capabilities. To maintain the contraption, the government raised the fees for ships arriving at Magong harbor.

Photo courtesy of Penghu County Cultural Affairs Bureau

In 1875, the aging structure was replaced with an 11-meter tall Western lighthouse built by British engineer David M. Henderson. It was named the Fisher Island Lighthouse (漁翁島燈塔). The lamp continued to upgrade over time, switching to calcium carbide in 1915, kerosene in 1938 and electrical light in 1966.

MILITARY IMPORTANCE

Qing sources mostly mention Xiyu under the context of its military significance due to its strategic position, with little mention of the daily lives of the people, states the Xiyu Annals.

The 1790 Brief Account of Penghu (澎湖紀略) was the first to provide comprehensive information about the island’s demographics, listing the various settlements and noting a total population of 2,893, with an additional 100-odd troops stationed there.

Although the Qing built several cannon batteries around the island in the late 1600s, when the Sino-French War broke out in 1884 they realized this was not enough and hastily constructed a fort on the southern shores.

However, the French invaded in March 1885 before they could install the cannons and went on to occupy the entire archipelago (see “Taiwan in Time: Foreign views of French-occupied Penghu,” March 28, 2021). They evacuated four months later.

After the war, Qing officials significantly upgraded Taiwan’s defenses, building four new forts in Penghu in 1887, two of them in Xiyu. The largest was the 8.15 hectare Xiyu Western Fort (西臺). Armed with four British-made Armstrong guns, it was the most powerful defensive structure in Penghu at the time, according to the New Penghu Annals (續修澎湖縣志). A smaller East Fort (東臺) was also constructed nearby.

After the Qing ceded Penghu and Taiwan to Japan in 1895, the troops hastily dismantled the defenses, and till this day most of the cannons have not been found.

FROM BOATS TO BRIDGE

Xiyu remained pretty much isolated from the rest of Taiwan until the completion of the Penghu Great Bridge in 1970. The only means of transport outside the island was by boat, and in addition to private vessels, the Japanese set up a ferry between Xiyu and Magong that ran four times per day. Weather conditions often halted traffic, whether it be typhoons during the summer or the devastating northeasterly winds during the autumn and winter.

The ferry broke down after World War II. The new township government rented a temporary vessel from Penghu Maritime Vocational School (澎湖水產學校), and other private entities offered irregular service until a comprehensive transport plan was installed in 1951 with a new ship built by the county office. Four regular public and private vessels connected different parts of Xiyu to Magong, and the 50-ton Guangwu (光武輪) was inaugurated in 1969.

Work on the bridge commenced in May 1965 employing local engineers and material, completing what the Xiyu Annals called the “number one bridge in the Far East” (遠東第一大橋). By contrast, the previous bridge to bear this moniker, the 1953 Xiluo Bridge (西螺大橋) connecting Changhua and Yunlin counties, relied on US aid and foreign technicians. Curiously, this bridge was also completed on Dec. 25.

Workers building the Great Bridge toiled directly above the perilous Roaring Gate, and seven lost their lives during construction. Ferry ridership dropped dramatically, leading to the decline of Daguoye (大?葉) fishing port where they originated. The Guangwu burned down in 1979 and was never replaced.

Due to the foundations being right in the middle of the Roaring Gate, as well as saltwater rain, the bridge deteriorated rapidly under heavy traffic. After several attempts to repair it, a new bridge was planned in 1984. This structure took 12 years to complete, and great effort was put into making it weather and corrosion resistant. During construction, however, the old bridge was shut down for repairs several times, forcing residents to revert to boat travel once more.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them