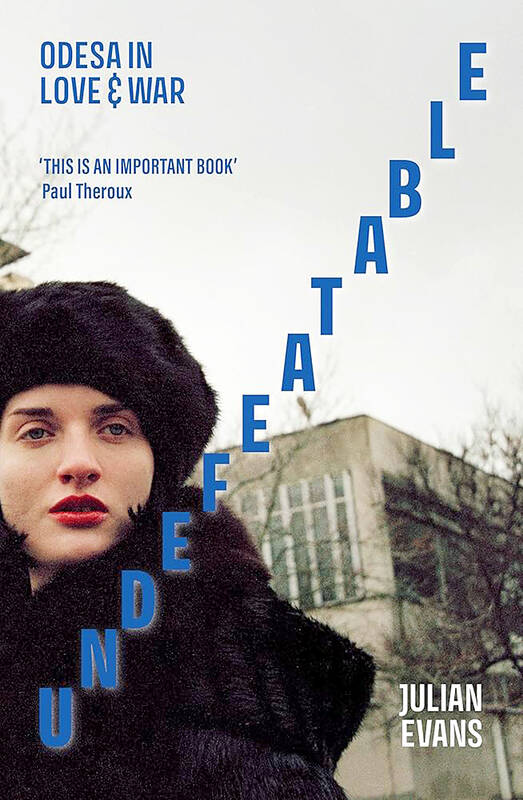

In 1994 the writer Julian Evans went on a 10-day cruise down the Dnipro River. Ukraine had won its independence three years before. The journey took Evans along an ancient route used by the “restless Vikings” who established Kyiv. His ship — the Viktor Glushkov — stopped off at Crimea and Yalta. Its final destination was the glittering Black Sea port of Odessa.

Evans was a veteran traveler. Nonetheless, the city was “unlike any place I had visited,” he writes — a “country beyond the back of a wardrobe” where anything could happen. It had merchants’ houses, acacia trees, a dandyish 19th-century opera and ballet theater, and wide neoclassical boulevards. It was ostentatious and self-made. There was kolorit: exoticism and flash.

After seven decades of communist decay, mafia goons roamed the streets. In its gangster heyday, Evans recalls, Odessa was a “dusty Sleeping Beauty being kissed awake by a guy in a blacked-out Mercedes with a handgun in the glove box.” Regional crooks dominated. The city was full of stories, and known for sarcasm and wit. It was home to Isaac Babel, the poet Anna Akhmatova and Bob Dylan’s Jewish grandparents.

For Evans, it was the beginning of a three-decade love affair with Odessa and its people. He returned five years later to make a radio program about Alexander Pushkin, another resident, and got chatting to a waitress called Natasha. He invited her for a drink. A courtship followed — with walks, Moldovan wine and letters from London. Evans converted to Orthodoxy and married Natasha in a monastery.

Later they spent languid summers in Odessa with their two children. Meanwhile, Ukraine was changing from a Moscow-style bandit state to a fledgling democracy and what Evans calls an “emerging unlikely paragon of freedom.” Ukrainians were willing to fight for their rights, in contrast to their supine neighbors. There were street revolts in 2004 and 2014: against election cheating and a corrupt Kremlin-backed government.

Evans’s new book is a brilliant portrait of a country and a city now under Russian attack. Most nights Iranian drones and Iskander ballistic missiles wallop Odessa, bringing murder and mayhem. The blossom-scented harbor promenade and Potemkin steps that enchanted Evans echo to Ukrainian anti-aircraft fire. Having failed to seize Odessa in the early weeks of his invasion, Vladimir Putin is busy destroying it.

The author’s relationship with the city lasted longer than his marriage, which eventually fizzled out. In 2015 he toured the then eastern frontline near Mariupol, following Russia’s covert part-takeover of the industrial Donbas region. In November 2022, he arrived in a missile-struck Odessa during a blackout. His mission this time was humanitarian: to donate a Nissan pickup to the outgunned Ukrainian army, plus tourniquets.

Evans is a wonderful writer and observer, a stylist as elegant and gloriously free-wheeling as the late Jonathan Raban. Each paragraph has a lapidary charm. There is plenty of history too, effortlessly told. Before the Vikings, Odessa attracted Greek colonists. Other settlers include Italian merchants and Tatars. It was always a place of migrants, and more than the southern imperial riviera capital of Catherine the Great.

The memoir offers a shrewd analysis of Ukraine’s present struggle and what it means. The British media has frequently got it wrong, Evans suggests. In 2014 it depicted Moscow’s attempted takeover as a fight between “Ukrainian nationalists” and “pro-Russian separatists.” The actual fault line was economic: between the country’s poor and super-rich. Ukraine’s oligarchs lit the “garbage fire” that made Russia’s war possible, Evans argues.

The nation’s fate now hangs in the balance. On the battlefield Russia is advancing. Internationally, there is a strong whiff of betrayal in the air, as Trump returns to the White House and Ukraine’s allies get tired. Trump has promised to resolve the war — borne from centuries of Russian oppression — in “24 hours.” It seems likely he will bully Volodymyr Zelenskyy into a “peace deal” on Moscow’s brutal terms.

Evans characterizes the invasion as fascist. The Kremlin’s goals of expansion and assimilation by force are identical to those of the Nazis in the 1930s, “if less efficiently executed,” he writes. It is “plain sordid imperial theft” and “robbery with violence.” If Putin prevails in Ukraine, he will gobble up other European nations. China and North Korea — which has sent troops to bolster Russia’s army — may launch grabs of their own.

After three years of all-out war, Ukrainians are exhausted. The west talks about moral principles, one disillusioned soldier tells Evans, but sends too few weapons to make a difference.

“Ukraine’s spirit is flagging from loneliness,” he says.

If Europe and America believe in freedom and democracy “we should not shy away from putting our soldiers on the ground.” There is little prospect of that happening.

During a visit in May, Evans finds young women sitting in ones or twos in a beachside restaurant in Odessa, enjoying the evening breeze. The Black Sea is cleaner than before. Dolphins appear. Missing from this dreamy scene are men. Some are at home, hiding from conscription. Others are fighting in trenches on the eastern front. Thousands lie in cemeteries under yellow and blue flags.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend