Common sense is not that common: a recent study from the University of Pennsylvania concludes the concept is “somewhat illusory.” Researchers collected statements from various sources that had been described as “common sense” and put them to test subjects. The mixed bag of results suggested there was “little evidence that more than a small fraction of beliefs is common to more than a small fraction of people.”

It’s no surprise that there are few universally shared notions of what stands to reason. People took a horse worming drug to cure COVID! They think low-traffic neighborhoods are a communist plot and call the police about KFC running out of chicken! We all think those other guys are the stupid ones.

If you would like to test your own common sense, the Pennsylvania researchers are running an online challenge (commonsense.seas.upenn.edu). Despite dark suspicions about my common sense, I was compelled to try, agreeing or disagreeing with statements, then deciding whether others would think like me.

Photo: EPA-EFE

Some were easy (“No one wants to get ill;” “Glue is sticky”), but some gave ample opportunity to overthink and second guess myself. Surely it isn’t silly to end a marriage if you don’t love someone? Is “loving people more than they deserve” an “aspect of kindness?”

How am I supposed to know anything about the body temperature of cats?

The worst bit was the maths (designed to check if intelligence and common sense are correlated — not particularly, apparently). I’m 49 and haven’t worked out two-thirds of anything since 1992: I had to draw 60 apples to stumble through a simple fraction, guess the full price for a discounted toaster and text my son for help. That exchange ended with me begging him: “Pretend this never happened.”

The verdict? A feeble 53/100 on the “commonsensicality” index (maths score undisclosed). Unwilling to accept my worst mark since year 10 physics, I tried again. And again. By the fifth attempt (yes, a total waste of my time), I had bumped my score up to 97/100. That is a victory for something, but definitely not common sense.

It’s always a pleasure to see something one has long advocated slowly become reality. The late August visit of a delegation to the Philippines led by Deputy Minister of Agriculture Huang Chao-ching (黃昭欽), Chair of Chinese International Economic Cooperation Association Joseph Lyu (呂桔誠) and US-Taiwan Business Council vice president, Lotta Danielsson, was yet another example of how the two nations are drawing closer together. The security threat from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), along with their complementary economies, is finally fostering growth in ties. Interestingly, officials from both sides often refer to a shared Austronesian heritage when arguing for

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary

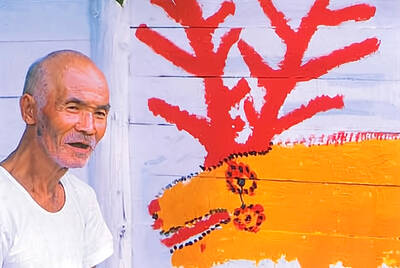

Nov.10 to Nov.16 As he moved a large stone that had fallen from a truck near his field, 65-year-old Lin Yuan (林淵) felt a sudden urge. He fetched his tools and began to carve. The recently retired farmer had been feeling restless after a lifetime of hard labor in Yuchi Township (魚池), Nantou County. His first piece, Stone Fairy Maiden (石仙姑), completed in 1977, was reportedly a representation of his late wife. This version of how Lin began his late-life art career is recorded in Nantou County historian Teng Hsiang-yang’s (鄧相揚) 2009 biography of him. His expressive work eventually caught the attention

Late last month the Executive Yuan approved a proposal from the Ministry of Labor to allow the hospitality industry to recruit mid-level migrant workers. The industry, surveys said, was short 6,600 laborers. In reality, it is already heavily using illegal foreign workers — foreign wives of foreign residents who cannot work, runaways and illegally moonlighting factory workers. The proposal thus merely legalizes what already exists. The government could generate a similar legal labor supply simply by legalizing moonlighting and permitting spouses of legal residents to work legally on their current visa. But after 30 years of advocating for that reform,