What Hillary Clinton lost was her chance to be the first female US president; what she has gained in the eight years since that wrenching disappointment is less clear.

“My life is richer and my spirit is stronger,” she insists, but her new book, Something Lost, Something Gained: Reflections on Life, Love and Liberty, reveals her to be also the victim of lingering PTSD.

Brooding about her defeat, she muddles the five-step grieving process and alternates between denial and anger, bargaining and depression. As yet, despite walks in the woods and romps with her grandchildren, she seems not to have arrived at acceptance. Just as Donald Trump continues to grouse about the supposedly stolen election of 2020, so Clinton shadow-boxes her way through endless reruns of her wonky, uncharismatic 2016 campaign.

An FBI official, she relates, recently commiserated with her about Trump’s victory and blamed the bureau for tripping up her candidacy when it reopened an investigation into her e-mails. Clinton spurns his offer of sympathy, snapping

“I would have been a great president,” and stalks away.

Later, she elaborates a morbid fantasy about the US in Trump’s second term, with troops in the streets and concentration camps for refugees. In 2016, Trump anatomized American malaise and boasted: “I alone can fix it.”

Clinton’s doomy scenario has a corresponding unspoken subtext. “I alone,” she seems to imply, “could have stopped him.”

ENTITLED

Her sense of entitlement leads her to experiment with appropriate titles for herself, if only the outcome had been different. In the 19th century, the first lady was sometimes called the lady presidentress, which for Clinton has a certain antique allure. She also wonders whether she could have got away with calling herself President Rodham Clinton, in deference to her parents, and to differentiate herself from her husband.

Deprived of power, she has had to settle for fame, and she moves in a blinding glare of publicity. When she teaches at Columbia University, her students are allowed five minutes in which to photograph her before the class begins.

Her buddy Steven Spielberg advises her about pitching a movie idea in Hollywood; she goes to Broadway plays — where she once “got two standing ovations just for showing up!” — with her bosom chum Anna Wintour.

Canoeing in rural Georgia, she just happens to be accompanied “by a small film crew.” At her most grandiose, she is something of a mythomaniac. She rails at an “alt-right” Web site that depicts Trump as Perseus and Clinton as the beheaded Medusa, but reveals that as a girl she modeled herself on Greek prototypes such as “Athena, the goddess of wisdom and war, and Artemis, the goddess of the hunt,” even asking her mother “if I could get a bow and arrow.”

Would that have equipped her to puncture the puffed-up Trump?

Clinton’s publisher, she says, wanted a volume of table talk; instead, she delivered a series of op-eds on universal day care, abortion law and her other “passion projects.” Informality does not come naturally to a woman who feels “the weight of civic responsibility” and even patriotically color codes her clothes for her “symbolic moments.”

INSTITUTIONALIZED

Those pressures have institutionalized her: she is as uptight as the Statue of Liberty. A section on her marriage briefly mentions Bill Clinton’s impeachment while saying nothing about the sexual lapses that provoked it. Perhaps she gives more away when she lightheartedly remembers Bill making “plans for his someday funeral.”

But then she astonishingly remarks that she feels “a lot of guilt about what my run for president did to Bill:” is she deflecting her own pain or injecting it into him?

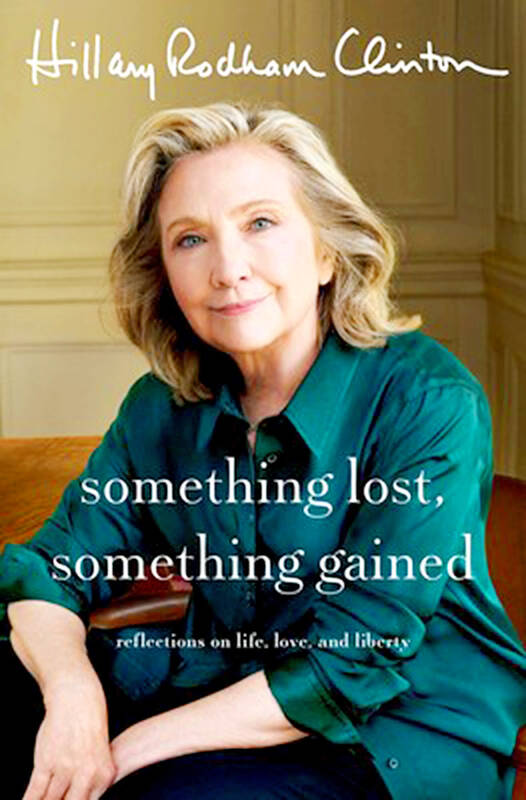

Dreaming about a coronation rather than an inauguration, she watches the 80-year-old Joni Mitchell at an awards ceremony regally “holding court from an armchair that looked like a golden throne,” with her cane as a scepter. This may be Clinton’s preferred persona: on the book’s cover, an unrecognizable photograph by Annie Leibovitz, another BFF, portrays her as an extravagantly maned lion queen.

Here, as always, Clinton retreats into official inscrutability, showing the world a sober and strictly public face.

“I take no pleasure in being right,” she says when Trump is convicted of 34 felonies.

Couldn’t she have allowed herself just a small illicit thrill of schadenfreude?

Clinton, now 76, concludes by anticipating another decade of strenuous activism. She feels “a responsibility for building the future;” meanwhile, however, she is receding into the past.

When she says: “I flew on Air Force One, dined with kings and queens and was constantly surrounded by armed guards,” she sounds like a soliloquist in a nursing home, ruefully revisiting her glory days while her fellow residents nod off. Whether in politics or not, as we age we are all monarchs nudged into abdication, or presidents arriving at the end of their allotted term. It’s a melancholy fate, but better, I suppose, than being binned like a limp lettuce after its sell-by date.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,