For the current Paris Olympics, Taiwan’s team of 60 athletes is now competing for the eleventh time as “Chinese-Taipei,” even as Olympic security guards and Chinese bullies prevent Taiwanese fans from cheering their athletes with signs that say “Taiwan.” But “Chinese Taipei” wasn’t always the name Taiwan used in the games.

Since the nation’s Olympic debut in 1956, its athletes have competed as “Formosa,” “Taiwan,” “the Republic of China,” and the now-familiar “Chinese-Taipei.” The team’s name has long been a contentious issue and this turbulent history is now examined in two new documentaries streaming for free on TaiwanPlus: What’s in a Name? A Chinese Taipei Story by director Garret Clarke, and Decathlon: The CK Yang & Rafer Johnson Story, directed by Frank W Chen (陳惟揚) and written by veteran CNN anchorman Mike Chinoy.

What’s in a Name?, a 20-minute documentary which has around 70,000 streams and been shared on social media by Taiwan’s Vice President Hsiao Bi-kihm (蕭美琴), asks the questions of how and why Taiwan must now compete as “Chinese, Taipei”?

Photo courtesy of What's in a Name?

The film begins with a livestream of an international freediving competition, in which the flag icon next to the Taiwanese competitor displays as a blank, a broken link. On camera, director Clarke then tells us that the icon is supposed to show the Taiwan flag, but it has been removed owing to pressure the Chinese government places on nearly all world sports bodies to block references to Taiwan.

“So really what this is all about,” says journalist Chris Horton in one of the film’s interviews, “is erasing Taiwaneseness and dehumanizing Taiwan.”

Street interviews find that most Taiwanese are baffled by the name “Chinese, Taipei.”

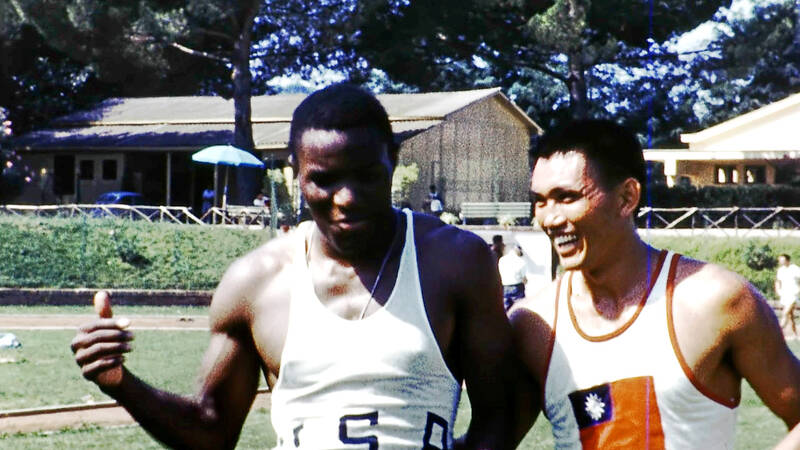

Photo courtesy of Decathlon Film LLC

“I think this name stops people from knowing who we are,” said one interviewee.

Another adds, “I wish we could use our official country name.”

CHINESE CIVIL WAR

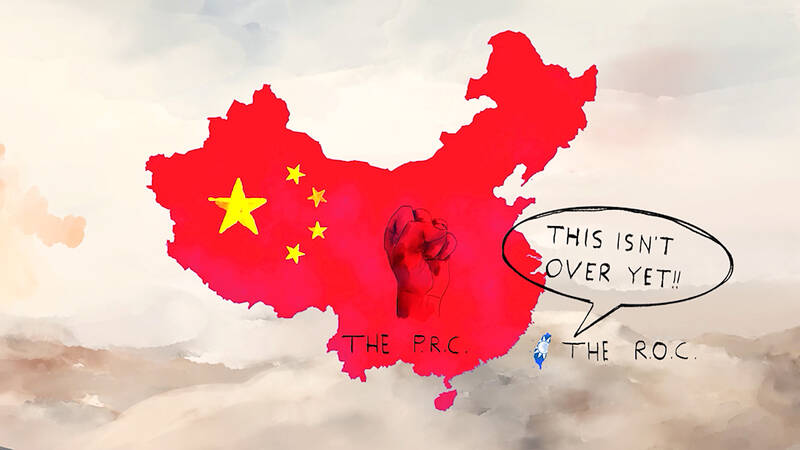

Photo courtesy of What's in a Name?

The root of Taiwan’s problem of Olympic representation goes back to the Chinese Civil War, which ended in 1949 with two separate governments –– the Republic of China (ROC) led by Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) on Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) led by Mao Zedong (毛澤東) on the Chinese mainland –– both claiming to represent the true “China.”

For the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, the PRC sent a team and pressured the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to bar Taiwan from calling itself “the Republic of China.” The IOC would have allowed Taiwan to compete under another name, but Chiang, unwilling to swallow this massive loss of face, boycotted the games.

The PRC withdrew from the Olympics in 1956 and would not rejoin the games again until 1980. Taiwan was able to use the “Republic of China” in 1956 in Melbourne, but in 1960, the IOC again insisted that Chiang’s regime use an alternate name. Chiang would have likely boycotted again in 1960 if not for one athlete, CK Yang (楊傳廣).

Photo courtesy of Decathlon Film LLC

Yang would in fact become the first person with a Chinese surname to ever win an Olympic medal and a national hero in Taiwan, but he was not actually Chinese. He was a Taiwanese aborigine from the Amis community, who, having emerged as a teen phenom in rural Taitung County, was ordered to compete in the decathlon by his Han Chinese coach.

Without clearly understanding all the event’s rules, Yang won the decathlon at the 1954 Asian Games in Manila. The press quickly dubbed him “Asia’s Iron Man.” He then moved on to the world stage at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, where he finished eighth.

In Melbourne, Yang for the first time met American athlete Rafer Johnson, the decathlon silver medalist, whom he then regarded as “my hero, my idol.”

Photo courtesy of Decathlon Film LLC

Over the years, this unlikely pair — a Taiwanese aborigine and an African-American –– developed a rivalry that blossomed into a lifelong friendship. Yang would attend Johnson’s wedding in California and taste American racism when forced to sit in the back of the bus with black people in the American south. Decades later, Johnson would fly to Taiwan for Yang’s funeral.

POLITICAL SYMBOLS

Their story is the subject of Decathlon: The CK Yang & Rafer Johnson Story, a 45-minute-long tale as heartwarming as it is rich in relevance to issues still fiercely contested today.

Photo courtesy of Decathlon Film LLC

“It’s such a wonderful, inspiring, poignant story that carries so many lessons about friendship and hardship and loyalty,” Chinoy said. “And what’s even more fascinating is that these two were among the earliest examples of athletes to become used as political symbols.”

For the Republic of China government, Yang offered a chance for political representation on the world stage. Johnson meanwhile became the first black man to carry the American flag for the US team at the Olympics and an early icon of the American civil rights movement.

“When LeBron James carried the flag last week at the opening ceremony in Paris, he was literally walking in the footsteps of Rafer Johnson,” Chinoy said.

Photo courtesy of What's in a Name?

The friendship between Johnson and Yang began to solidify in 1958 after competing against each other at a track meet in the US. Afterwards, Yang enrolled at UCLA to train together with Johnson under legendary track coach Ducky Drake. By the time of the 1960 Rome Olympics, the pair were the world’s two top-rated decathletes.

The film is built around their duel in Rome, where, owing to Yang’s chance for a medal, Taiwan’s team deigned to compete as “Formosa.” In the competition, Yang won six of the decathlon’s first nine events, but Johnson won by big margins in the other three and was ahead on points. Going into the decathlon’s final event, the 1500 meter race, it was anyone’s game.

Yang won that final race, but Johnson kept the points lead and took the gold medal. Yang’s silver was however Taiwan’s first ever Olympic medal and made him a hero at home.

Photo courtesy of What's in a Name?

Chinoy got to know Johnson from 2010 in Los Angeles and, sitting with the aging athlete and his wife Daisy in their kitchen, heard his story firsthand. Chinoy’s close friend and fellow journalist, former Asian Wall Street Journal reporter John Krich, had meanwhile in 2006 chased down CK Yang in Taitung and shot five hours of video interviews. Yang died just one year after Krich filmed him, and Johnson died in 2021.

“We felt we really had to do this story at some point, but the question was just when,” said Chinoy.

That opportunity came in 2019, after Chinoy met Taiwanese-Canadian director Frank W Chen, whose previous credits included a documentary on Taiwan’s biggest baseball star, Late Life: The Chien-Ming Wang Story. Together, they began putting together a jigsaw puzzle of disparate interviews, archive footage and the audiobook of Rafer Johnson’s autobiography which was narrated by Johnson himself.

Photo courtesy of What's in a Name?

SPORTS DIPLOMACY

Following Yang’s silver medal in the 1960 Rome Olympics, his own story remained intertwined with Taiwan’s struggles in sports diplomacy. In 1964, he was again a medal favorite at the Tokyo Olympics, but just before the start of the decathlon, he was poisoned by a teammate and competed poorly. The teammate, Ma Ching-shan (馬晴山), defected from Taiwan to the PRC during the games.

Taiwan’s Olympic team meanwhile competed as “Taiwan” in Tokyo 1964 and again in Mexico City in 1968. Then in Munich in 1972, it once again appeared as the “Republic of China” –– though for the very last time.

By the mid-1970s, China was coming out of its isolationist shell and resuming formal diplomatic relations with world powers. Beijing insisted that it alone be recognized as “China” and that any national title including “China” should be denied to Taiwan and its KMT government.

When Taiwan’s team arrived at the Montreal Olympics in 1976, the host nation Canada, which had just resumed diplomatic relations with China the previous year, refused to allow the team to compete as the “Republic of China.”

By this time Yang had become the national team’s track coach. In What’s in a Name?, we see archival news footage of him interviewed in front of a Montreal stadium with a group of befuddled Taiwanese athletes standing behind him. “I didn’t expect it to be like this at the last moment,” he tells the reporter.

The Canadians would have allowed Taiwan to compete as “Taiwan” that year, but on the eve of the games with Taiwan’s Olympic team already in Montreal, the KMT government refused and withdrew as a matter of pride. In 1980, the KMT again boycotted the games for similar reasons.

The name “Chinese, Taipei” was finally introduced in 1981, and though Chinese pressure was a factor, this compromise was in fact proposed by the KMT leadership.

“A lot of people think this label came from China,” Clarke said. “So when I made this, I wanted to make sure people understood that it was the KMT that made this decision. It was an own goal, basically. And it continues to haunt Taiwan’s Olympic team today.”

Both documentaries are now available to stream for free on www.TaiwanPlus.com and on the TaiwanPlus Docs YouTube channel.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,