June 3 to June 9

If you wanted a beer in Taiwan before 1987, it was almost certain to be Taiwan Beer — unless you had special connections. But by June of that year, consumers suddenly had nearly 100 types of foreign brews to choose from, with Heiniken, Budweiser and Miller among the major brands.

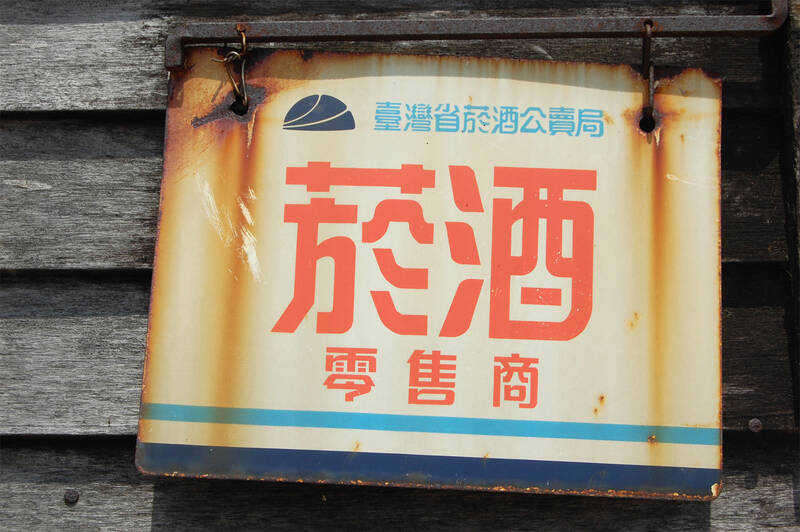

The government still held a monopoly over production, delivery and sale of all local alcoholic beverages — a practice started in 1922 during the Japanese colonial era — but the lifting of the ban on foreign products on Jan 1, 1987 dealt a major blow to one of the nation’s main revenue sources.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Despite calls to relinquish their control over the local industry, the government held on until the 1990s when their bid to join the WTO compelled them to finally ease regulations.

The passage of the Tobacco and Alcohol Administration Act (菸酒管理法) on June 4, 1999 provided the legal framework, and in 2002 the Taiwan Tobacco and Wine Monopoly Bureau (臺灣省菸酒公賣局) gave way to the Taiwan Tobacco and Liquor Corporation, ending 80 years of state dominance over the industry.

INHERITED MONOPOLY

Photo courtesy of Academia Historica

Prior to 1922, the Japanese colonial government already had a monopoly on Taiwan’s opium, tobacco, salt and camphor industries. However, struggling financially in part due to post-World War I economic depression, authorities added alcohol to the list, shuttering over 200 businesses and banning private brewing. Matches, measuring instruments and petrol were later added to the list.

When the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) arrived in Taiwan in 1945, it continued the existing system. “The new government had yet to find an alternate source of income, so it decided against abolishing the monopoly to avoid disrupting Taiwan’s economic stability and development,” a monopoly bureau report states.

The KMT banned opium and transferred salt and petrol to other departments, leaving the newly-formed Taiwan Provincial Monopoly Bureau with five industries. Many production facilities were damaged from Allied airstrikes during the war and were in need of repair, resources were also in short demand, but the bureau made do with what it had.

Photo courtesy of Chiayi City Cultural Affairs Bureau

Fan Ya-jiun (范雅鈞) writes in “Study of the alcoholic beverage monopoly in postwar Taiwan, 1945-1986” (二次戰後臺灣酒業專賣之研究, 1945-1986) that the bureau was plagued with corruption and misconduct, and first monopoly bureau chief Jen Wei-chun (任維鈞) was fired over a major scandal involving trade bureau chief Yu Pai-hsi (于百溪). The two were never prosecuted, leading to public outcry.

ENFORCING THE RULES

Finding it difficult to squash private production, the local black market and international smuggling (mostly to China), bureau agents often went after illegal street vendors. A scuffle over an elderly woman selling contraband cigarettes in Taipei triggered the 228 Incident of 1947, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed.

Photo courtesy of Hualien County Cultural Affairs Bureau

After 1947, only alcohol and tobacco were retained. Since the bureau belonged to the Taiwan Provincial Government, Kinmen and Matsu were allowed to produce their own alcohol as they fell under Fujian Province. However, they still had to go through the monopoly bureau to sell their kaoliang to Taiwan.

The bureau raked in much money for the government, contributing to 18.11 percent of the national revenue in 1950 and 22.62 percent in 1956. Fan writes that during the 1950s, state finances were so tight that the bureau had to transfer its revenue daily to the national treasury to keep the government operating.

Authorities made a serious effort to crack down on all illegal behavior in 1950, with its agents opening over 12,000 cases that year alone. Some merchants turned to purchasing low-grade alcohol from the bureau and distilling it into high-grade liquor to turn a profit, but the practice was banned in 1955 after the passage of a new law.

Photo courtesy of Academic Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica

ROAD TO PRIVATIZATION

As Taiwan’s economy took off in the 1970s, the tobacco and alcohol monopoly’s importance to national coffers had greatly diminished by the 1980s. It was also a rare practice, as a 1977 study showed that only four countries in the world exercised complete government monopoly over alcohol.

The monopoly by then was plagued by bureaucracy and lack of competition. Since the central government and provincial government split the profits 65-35, the bureau had to answer to both bodies regarding almost all decisions. When the two sides could not agree, the solution was always to maximize revenue and minimize expenditure, preventing the bureau from focusing on business development and meeting market needs.

Fan writes that management inefficiency led to poor quality products and outdated packaging, and supply often failed to meet demand. People began making their own alcohol again in the late 1970s, leading to numerous cases of alcohol poisoning. Hoarding was also a problem, especially before price hikes.

As early as 1985, the Executive Yuan’s Economic Reform Committee urged the government to privatize the industry. Chen Chia-wen’s (陳佳文) 1986 “Study of Taiwan’s tobacco and alcohol monopoly system and policy” (我國菸酒專賣政策及專賣制度之研究) also concluded that maintaining the monopoly was not necessarily better than collecting taxes from a free market, noting that the bureau’s business performance was “unsatisfactory.”

However, these suggestions were not heeded. A 1987 Executive Yuan report merely stated that they would try to improve the monopoly, and the issue of privatization was “not to be discussed further.”

The lifting of the ban on foreign alcohol was pushed through after more than a year of negotiations with the US, with the Americans threatening to stop importing Taiwanese textiles and other materials if the government did not open up the market. The bureau simply could not compete after this, as its contribution to the national revenue fell to 10 percent in 1987 and 4.65 percent in 2001, according to a National Taiwan Library document.

Due to Taiwan’s bid to join the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (precursor to the WTO), the central government began supporting privatization in the 1990s despite strong opposition from the provincial government. With Taiwan’s ascension to the WTO on Jan. 1, 2002, the state monopoly finally came to an end.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the