Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985).

The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office.

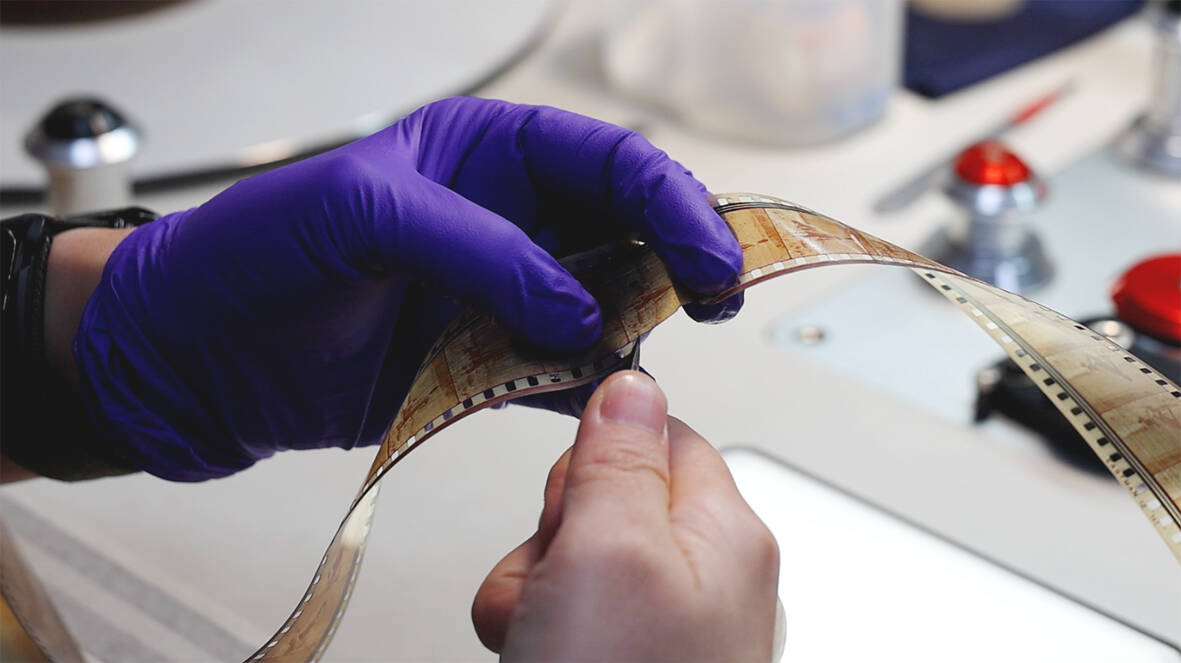

Photo: Billy Wu

Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration.

“It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful filmmakers. “We were lucky.”

For Taiwanese-language cinema, an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 films were produced between 1955 and 1981, according to TFAI. Fewer than 200 remain, though others might be rediscovered.

Photo courtesy of TFAI

HOW FILM WAS LOST

The Clown and the Swan survived only because its producer, gangster Wu Kung (吳功), loved cinema and kept the negatives. Indeed, according to Chu Taiwan’s film industry in the 1970s and 1980s was mostly controlled by organized crime.

“Theater owners paid NT$40 million for package deals,” he says. “Gangsters spent NT$10 million on production and pocketed the rest.”

Films were made by different gangs for the purposes of laundering money, and discarded them after theatrical runs.

Even when theaters didn’t return the prints, the negatives were used for other purposes — as shirt collar stays, for example, or padding for flip flops. Professor Robert Chen (陳儒修) of National Chengchi University’s Department of Radio and Television says that there was no awareness at the time of the importance of film preservation.

By the 1990s, the industry had collapsed. Taiwan loosened film import controls during trade talks tied to WTO accession and negotiations with the US, trading away protections for the film industry to safeguard agriculture.

Photo courtesy of Chu Jhih-Jie

Local production fell from 81 films in 1990 to 16 in 1999, according to the Cinema Yearbook in the Republic of China: 1990–1999.

Data from the Taiwan Creative Content Agency (TAICCA) shows that today foreign films still account for 89 percent of theatrical releases.

TFAI Chairman Arthur Chu (褚明仁) says major rescue efforts in the 1990s laid the groundwork for today’s restorations.

But Taiwan’s lack of major studios and the absence of a legal mandate for film preservation meant that original negatives were scattered and difficult to trace.

Some materials were recovered by chance. The institute once found 200 reels in the basement of a San Francisco Chinatown theater, including Love in Ryukyu (琉球之戀), a Taiwanese-language color film that many believed had been lost.

RACE AGAINST TIME

TFAI today holds nearly 180,000 reels, but many are badly degraded after decades of improper storage.

In Taiwan’s humid climate, a major threat is vinegar syndrome, which causes the film base to become brittle and warp as it releases acetic acid.

Even in climate-controlled vaults, deterioration doesn’t stop. The result is a technical race against time, driven as much by patient human labor as by luck.

A badly damaged reel can take a month just to prepare for scanning.

Wang Yu-jen (王鈺禎), a digital restoration technician at TFAI, handles one of the most delicate stages: stabilizing footage and removing defects frame by frame.

“Ten minutes of footage can take a month to restore if you’re lucky,” Wang says.

She recalls spending more than half a year on a single 1980s Taiwanese classic, The Story of a Small Town (小城故事), because mold had damaged large sections of the print.

Ethics complicates the work. TFAI follows International Federation of Film Archives guidelines, prioritizing faithful restoration over “beautification.”

When the institute restored Tsai Ming-liang’s (蔡明亮) Vive L’Amour (愛情萬歲) in 4K, it asked the director to personally supervise color grading.

“The goal is always to return the film as close as possible to its original state,” says Watson Lee (李仲豪), supervisor of TFAI’s Division of Preservation and Restoration. “[Tsai’s] supervision ensured it matched what was intended at the time.”

Quality, however, is costly. Each restoration can cost millions per film, and TFAI has only six restoration technicians, few conservators and one sound restorer.

“We do our best within the time allowed,” Wang says. “Some films can only be restored so much.”

CULTURAL RESCUE

But restoration is not just technical repair. It is cultural rescue.

Wang once recognized footage from her hometown in Tainan while working on a project.

“It felt personal,” she says.

Every film also functions as a document. Beyond plot, it encodes the political, economic and cultural textures of its time.

The Story of a Small Town, for example, captures a Taiwan in transition: the completion of the Sun Yat-sen Freeway and the Taiwanization movement that emerged as the US broke diplomatic ties in the late 1970s.

“Film restoration and preservation are a vital part of safeguarding historical memory,” Chen says. “The work must go back to the negatives.”

Iris Du (杜麗琴), TFAI’s director, frames the institute’s mission as identity reconstruction.

She says that through films, documents and audiovisual records, we can reconstruct the answers to questions like who we are and how Taiwan became what it is today.

“Our mission is to reintroduce films to contemporary audiences and reinterpret them in today’s context,” Du says.

THE LIMITS OF REVIVAL

But even with the highest capacity in Asia, the current pace of 10 to 12 films a year means it will take decades to process the existing archive.

Taiwan’s talent pipeline remains narrow. Aside from Tainan National University of the Arts’ lone graduate program, there is no comprehensive training in film preservation.

Still, the cost of inaction is higher.

“If nothing is rescued, that memory disappears,” Chen says.

The institute’s work also restores the legacies of filmmakers and performers whose careers were nearly erased.

Golden Horse-winning actress Lu Hsiao-fen (陸小芬) still remembers seeing herself on screen again at a restoration screening.

“It brought back a rush of mixed emotions,” Lu says. “The long waits, the heartbreaks and the hard-won victories all resurfaced.”

Hsu Pu-liao never got that moment.

At the 40th anniversary screening of The Clown and the Swan, the audience laughed just as they did in 1985.

“Hsu gave me my career,” director Chu says. “I want the next generation to know Taiwan had this era, had this person.”

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

Last month, media outlets including the BBC World Service and Bloomberg reported that China’s greenhouse gas emissions are currently flat or falling, and that the economic giant appears to be on course to comfortably meet Beijing’s stated goal that total emissions will peak no later than 2030. China is by far and away the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, generating more carbon dioxide than the US and the EU combined. As the BBC pointed out in their Feb. 12 report, “what happens in China literally could change the world’s weather.” Any drop in total emissions is good news, of course. By