Jan. 12 to Jan. 18

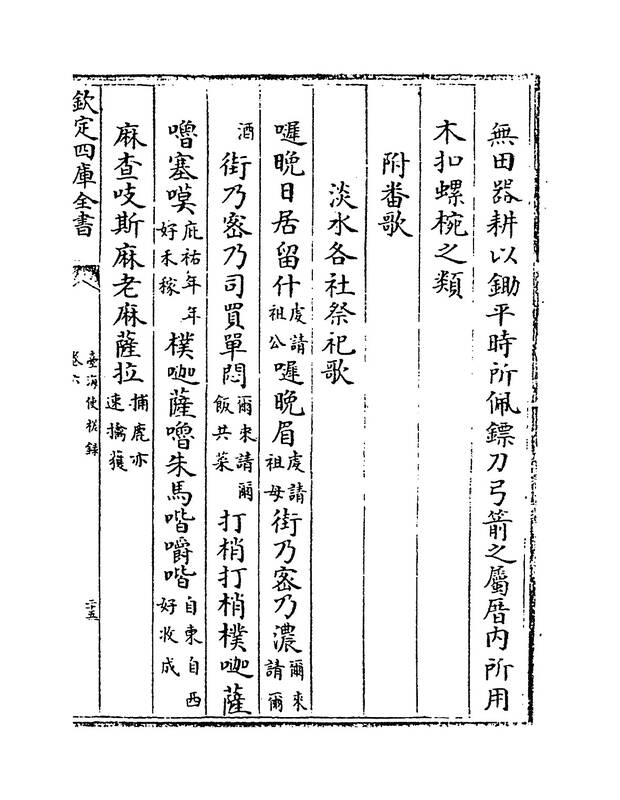

At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌).

The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season.

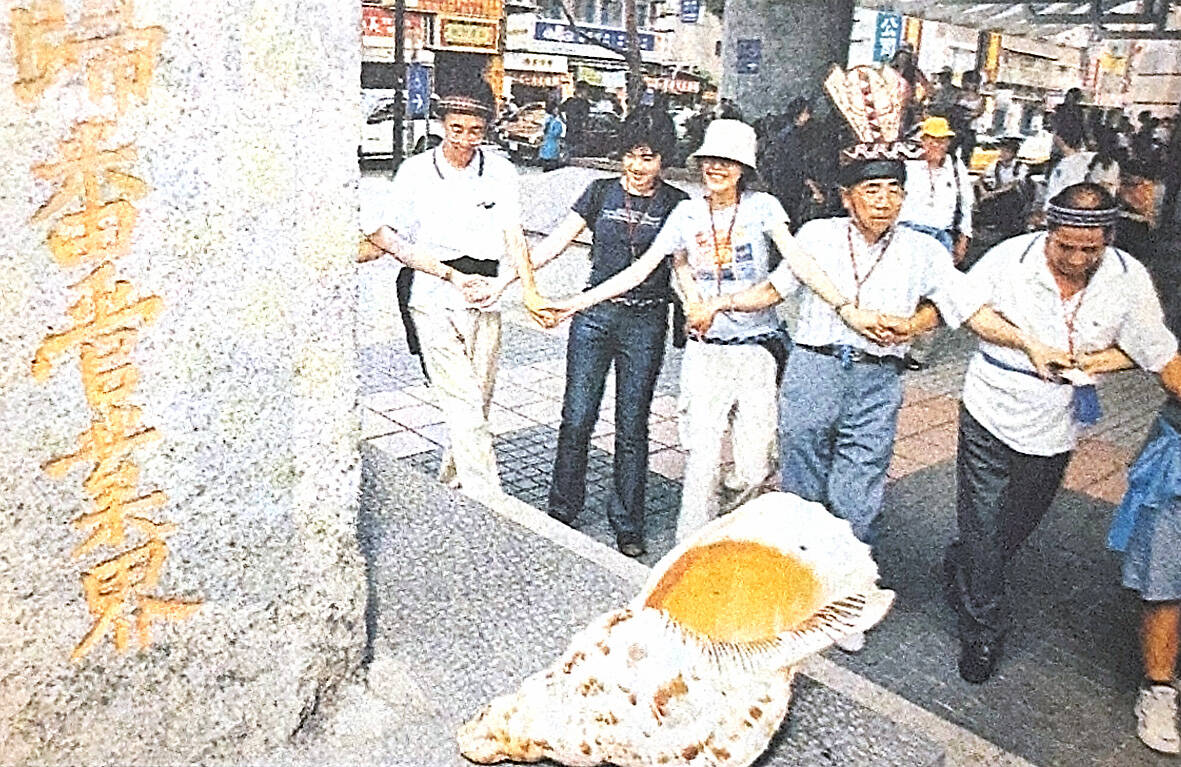

Photo courtesy of Chen Kun-mu

The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the Pingpu (plains Indigenous) people who once inhabited much of northern Taiwan. There was not much tangible heritage left, as the communities had been assimilated and displaced over the past several centuries.

After lunch, the guides revealed that the song was first recorded in 1722 by a Qing Dynasty official and later reconstructed in 2003 during the Ketagalan cultural revival movement. The melody was provided by the late Pan Hui-yao (潘慧耀), son of Pan Shui-tu (潘水土), who founded the Independence Presbyterian Church in Taipei’s Xinbeitou (新北投) featured in the previous “Echoes of Kipatauw” article (“A lasting Christian legacy,” Dec. 28, 2025). Pan recalled a Ketagalan tune his grandmother sang that seemed to fit the lyrics. The song was then performed, led by Ketagalan descendant Chen Te-sheng (陳德勝).

This encounter led me to apply to Tree Tree Tree Person Project’s (森人) writing residency focusing on the former Ketagalan settlement of Kipatauw, which encompassed much of modern day Beitou. During months of research, the song continued to surface in different settings.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PINGPU AWAKENING

In 1722, Huang Shu-ching (黃叔璥) was sent to Taiwan as imperial high commissioner. During his travels, Huang took a keen interest in local culture, including visits to Indigenous communities. His book, Records of the Mission Across the Taiwan Strait (臺海使槎錄), includes a number of Indigenous songs.

Han Taiwanese settlers soon began arriving in large numbers to northern Taiwan. As detailed in earlier installments of “Echoes of Kipatauw,” Kipatauw communities gradually adopted Han customs and languages over the next two centuries, losing land, privileges and even identity under Japanese and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule. Their language was last recorded in 1937. Today, the Pingpu remain unrecognized by the government, although a law passed in October last year may change this.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Long discriminated against and marginalized, Indigenous groups began fighting for their rights in the 1980s. The Pingpu, including the Ketagalan, joined the movement in the early 1990s. In 2001, the Taiwan Pingpu Indigenous Association was formed to advocate for official recognition.

The Ketagalan movement emerged from the 1994 push against the proposed Fourth Nuclear Power Plant in New Taipei City’s Gongilao District (貢寮). When it was discovered that the plant could threaten several potential Ketagalan archaeological sites, preservationists and Ketagalan residents from the nearby Sandiao (also known as San Tiago) settlement began organizing protests and cultural events.

KETAGALAN REVIVAL

Photo: Liu Hsin-te, Taipei Times

Sandiao resident Pan Yao-chang (潘耀璋) told reporters that since many Ketagalan were unaware of their identity, culture and language, he started the Ketagalan Association to reclaim their past so that future descendants would not have to endure the sorrow of this disconnect.

Still, many Taipei residents were confused when then-president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) renamed Jieshou Road (介壽路) to Ketagalan Boulevard in 1996, a move that did not fix the issue of official recognition.

Around this time, Chen Kun-mu (陳昆睦) became interested in Pingpu culture through researching the history of Tienmu for the Society of Wilderness. A Han Taiwanese, he spent the next few years visiting Pingpu communities across Taiwan. He later met Chen Te-sheng and was invited to assist at the Pingpu Indigenous Association, where he formed a friendship with then secretary-general Pan Hui-yao, a passionate advocate.

Photo courtesy of Chen Kun-mu

Pan’s family originated from Kipatauw’s upper settlement near today’s Guizikeng (貴子坑). The Japanese forcefully acquired most of their land during the 1910s but a few families remained, including his grandmother. Born in 1928, Pan visited her there as a child and learned several Ketagalan songs, which he remembered many decades later. When he was in the US, he taught some of these songs to Chen Kun-mu and Chen Te-sheng for a cultural event.

REBIRTH OF THE SONG

Chen Kun-mu and cultural researcher Wu Chih-ching (吳智慶) then traveled across northern Taiwan trying to locate descendants of the 19 or so traditional settlements.

In 2002, they organized a series of Ketagalan events beginning with the blooming of coral tree blossoms in April and May, which traditionally marked the start of the harvest season and a new year. Participants visited the various settlements, and the main ceremony was held in June. Since the Ketagalan preserved few customs, they recreated costumes and learned dances from the neighboring Kavalan people.

Wu wanted to include a ritual song in the following year’s event in Sandiao, but he could not find anything besides the one recorded by Huang in 1722. He later showed it to Ketagalan activist Pan Chiang-wei (潘江衛), who was able to read it in Taiwanese. Chen Te-sheng then transliterated it into the Latin alphabet, allowing Pan to connect it to his grandmother’s melody. About 200 to 300 Ketagalan participated that year, Wu says, and the group even received special permission to enter the nuclear plant, which was under construction, to pay their respects at an ancestral gravesite.

Chen Kun-mu recalls how Pan, despite suffering from gastric cancer, insisted on flying back to Taiwan in October 2004 to attend a nationwide Pingpu gathering in Tainan. He performed the song on stage for the last time, and died soon after returning to the US.

STILL BEING SUNG

The song resurfaced during an interview with Pan’s widow, Liang Fen-ying (梁芬英). While discussing Pan’s family history, she mentioned that his grandmother used to sing Ketagalan songs — then she sang the ritual tune from memory. A devout Christian in her 90s, she only began researching Pingpu history after her husband’s death. She hopes that the government will one day acknowledge the now-demolished church George Leslie Mackay built for Kiptauw in 1893.

The song appeared again a few months later at the Independence Presbyterian Church, where Pan Hui-yao’s younger brother, Pan Hui-an (潘慧安), led singing practice for an upcoming Ketagalan autumn festival. On Nov. 5, members from different Ketagalan settlements gathered in front of the Ketagalan Culture Center in Beitou and performed the song along with a Christian hymn set to an ancient Pingpu melody with Taiwanese lyrics.

There’s still more work to be done to fully translate the song into the original language. Yet more than three centuries after it was first recorded, it remains alive and continues to be sung.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades