Like many young Taiwanese men who recently graduated from university, George Lee (李芳成) isn’t quite sure what he’ll do next. But some of his peers surely envy what he’s already achieved.

During the pandemic, while staying with his brother in California, Lee started an online food page, Chez Jorge. At first, it was a straightforward record of what he cooked each day, with many of the dishes containing meat.

Lee soon began to experiment with plant-based dishes, specifically vegan versions of Taiwanese dishes he was already familiar with.

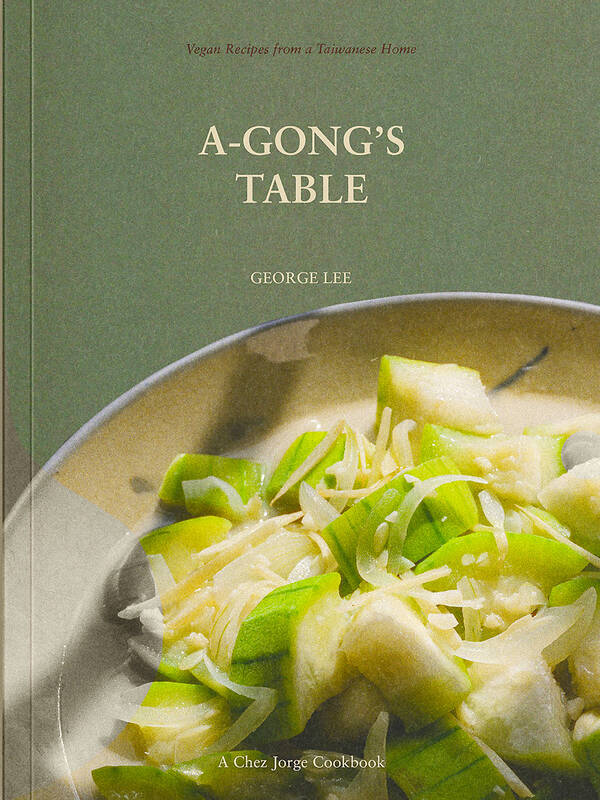

Photo courtesy of Random House

“Very often, I found myself awed by not only how delicious they were, but also by how little I missed meat,” he tells the Taipei Times.

Not every post focuses on a Taiwanese dish, however. Lee has shown his followers how to make kung pao “chicken” (with the poultry replaced by okara, the pulp left over after making soymilk or tofu) and a meat-free version of Malaysia’s nasi lemak. He’s also demonstrated chocolate tofu donuts, vegan “meat” floss, and hot and sour soup, the last featuring vegan ingredients in place of the usual pork, pig’s blood and egg.

His snowballing social media presence (as of this April, he had around 593,000 followers on TikTok and close to 700,000 on Instagram) eventually led to a Random House book deal.

Photo courtesy of George Lee

A-Gong’s Table: Vegan Recipes from a Taiwanese Home, which was published on April 30, is an exploration of foodways inspired in part by the a-gong (阿公, “grandpa”) of the title. According to Lee, his maternal grandfather was ultra-serious most of the time — but he was also a man who tremendously enjoyed good homecooking.

When Lee was 17, his grandfather passed away. As is common in Taiwan, close relatives temporarily became vegetarian, so as to ease the deceased’s journey into the afterworld. Lee writes in his book’s introduction that, by the end of that 100-day period, he’d “lost the appetite for chunks of meat that required a fork and a knife. I frequented vegetarian restaurants because they offered the variety of vegetables and legumes I had grown accustomed to. I didn’t think of it consciously then, but my outlook on food had changed.”

The book includes more than 80 recipes, including 12 breakfast items, 11 “little eats,” 17 mains, plus soups and festival foods like popiah rolls (潤餅, runbing — aka spring rolls). For the majority of these dishes, he provides the name in Hoklo (the local language also known as Taiwanese) as well as Mandarin.

Photo courtesy of George Lee

Of all the recipes he’s devised, Lee expresses particular satisfaction with his plant-based facsimile of braised pork over rice (滷肉飯). In A-Gong’s Table, he refers to it by a name used in many Taiwanese vegetarian restaurants: sulufan (素滷飯).

His determination to replicate the stickiness-in-the-mouth feeling one gets when eating the meat-based version led him to test no fewer than 15 iterations.

Knowing that pig-skin gelatin is a key component of braised pork over rice, Lee tried substitutes like peach resin, golden fungus and blended-up mountain yam.

Photo courtesy of George Lee

“I eventually settled for adding extra oil. You really can’t skimp on oil in many of these vegetarian dishes, because gluten and soy substitutes for meat are fatless,” he says.

Lee spent the summer of 2019 training as a chef at Le Cordon Bleu’s cooking school in Paris. When it comes to vegan cuisine, however, he says he found what he learned by watching Buddhist nuns prepare his family’s mourning meals was far more useful.

Working alongside friend Laurent Hsia (夏啟鐸), who took all of the photos in the book, Lee researched and wrote A-Gong’s Table while an undergraduate student at the University of California, Berkeley. He initially studied Chemistry, then switched to majoring in English.

He says he’s still considering his next steps.

“Working in restaurants and pursuing more written work on the side is a big possibility. As opposed to traditional cookbooks, I’m now more interested in art and poetry books, or how I might traverse between the genres and forms. Food will always be an element in my writing, I’m sure.”

Lee stresses that it’s never been his intention to convert anyone to a plant-based diet, and he’s the first to admit he doesn’t rigidly adhere to veganism. Whenever he cooks for himself, he makes plant-based dishes, but now he sometimes eats eggs, dairy products or the very occasional piece of fish or seafood.

His friends and family members have never expressed disapproval of his dietary choices, he says.

“They’ve always been accepting, though reintroducing fish to my diet was something my mother suggested. She was worried I wasn’t getting enough nutrition, and actually she was right, I did feel better. My limbs didn’t feel as cold anymore,” he says, explaining that, from a traditional Chinese medicine perspective, his body was too “cold” (寒, han), perhaps due to a weak circulation.

He’s noticed, however, that conversations about veganism in Taiwan often take a different direction compared to those he’s had in the US.

“My friends in Taiwan typically share stories about parents or relatives who are Buddhist vegetarians. In America, they’re more likely to talk about themselves or a peer who took the initiative to eat plant-based foods after, say, watching a documentary,” says Lee. This difference “encouraged me to enlarge on certain Buddhist aspects of the storytelling in the book,” he adds.

Katy Hui-wen Hung (洪惠文), who’s met Lee a number of times, says she’s been greatly impressed by his enthusiasm for experimenting with new ingredients. For instance, after a recent trip to Pingtung County, where he experienced millet-based dishes, he made popiah rolls and sticky-rice dumplings using millet.

“His book is refreshingly free of politics. And rather than try to convert people to veganism, it’s more a celebration of loving memories,” she adds.

A local history and culture enthusiast (and co-author with this writer of a book on Taiwan’s food history), Hung points out that being able to contemplate a vegan diet is proof that Taiwanese nowadays are privileged compared to their parents and grandparents. For people of her generation — Hung attended university in the early 1980s — eggs were an essential source of protein, she says.

Mai Bach, cofounder of the Taipei-based vegan restaurant group Ooh Cha Cha Ltd (自然食), is among those looking forward to A-Gong’s Table.

“I believe George is super-talented and I love the perspective he’s taking, emphasizing roots and ancestral knowledge over individual contributions,” says the Californian.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,