May 6 to May 12

Those who follow the Chinese-language news may have noticed the usage of the term zhuge (豬哥, literally ‘pig brother,’ a male pig raised for breeding purposes) in reports concerning the ongoing #Metoo scandal in the entertainment industry.

The term’s modern connotations can range from womanizer or lecher to sexual predator, but it once referred to an important rural trade. Until the 1970s, it was a common sight to see a breeder herding a single “zhuge” down a rustic path with a bamboo whip, often traveling large distances over rugged terrain to service local families. Not only did the practice reduce inbreeding, it allowed farmers to castrate their male pigs for superior meat quality.

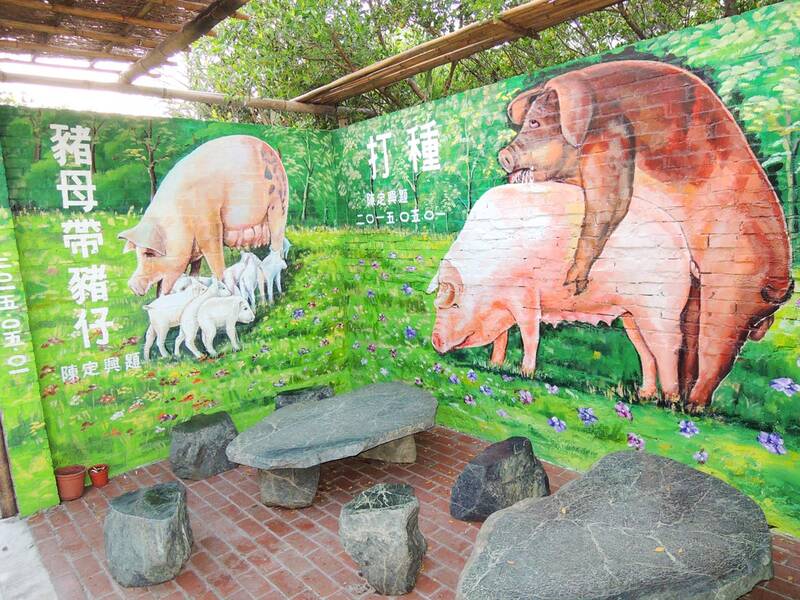

Photo: Yang Chin-cheng, Taipei Times

Although most zhuge breeders were poor, old or disabled men who had few means to make a living, some got rich through their acumen in producing robust, virile zhuge with highly coveted genes. The Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister newspaper) in 2010 reported on Changhua (彰化) breeder Chen Jung-tang (陳榮堂), who was able to purchase three apartment buildings and send all three children to private school through this trade alone.

However, the profession, known as “qian zhuge” (牽豬哥) in Mandarin and “khan ti-ko” in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese), was also somewhat stigmatized due to its sexual nature in the conservative countryside, and some breeders wore their conical hats low to conceal their faces. It was common in those days for parents to tell their children that if they didn’t study hard, they would end up doing “qian zhuge.”

By the 1980s, the bamboo whip had been replaced with a motorized three-wheeled cart, and asking prices were at an all-time high. But the industry was already in steep decline due to the advent of large-scale pig farming where the owners raised their own breeding males (also known as boars) and used artificial insemination.

Photo courtesy of Changhua County Cultural Affairs

Today, the practice has all but disappeared, but the term survives in the popular lexicon.

PIG REPRODUCTION

Almost all rural households in the 1950s and 1960s raised pigs to supplement their income. They were easy to keep, their excrement made for quality fertilizer and they were also essential as sacrifices during weddings and other ceremonies. Each family usually owned a pig or two at a time, and with most males castrated, when the sows were in heat they would contact the zhuge breeder.

According to a Harvest (豐年) magazine article, “qian zhuge” seemed relatively easy compared to other farm labor, but a lot of know how went into ensuring that the pigs mated successfully and as quickly as possible — including “guiding” and prodding them during the act if needed.

“An outstanding male pig did not require the owner’s assistance, and could complete the mating independently in an elegant fashion,” a Ministry of Agriculture article states.

Breeders only got paid if the mating succeeded; otherwise they would have to wait until the female was in heat again and then travel all the way for a second attempt. Families who required such services often lived in remote areas, and a journey could take up two hours. Some breeders received bonuses based on how many piglets the coupling produced.

The owners periodically splashed water on the zhuge to keep him cool during the journey, and fed him duck eggs after the job was done. Since pigs did not evolve to travel long distances or follow directions and were prone to digging in the ground every few steps, the zhuge had to be trained for the job from a young age. They could mate as much as twice per day.

STIGMATIZED WORK

Even though it was taboo to talk about sex openly back then, “zhuge” was the answer to a popular children’s riddle: “What wears a black cassock and traverses the hills and mountains to find a wife?”

Writer Huang Chun-ming (黃春明) says in a 1998 seminar on the Taiwanese language that “qian zhuge” was the first sex education for many rural children, as they finally realized what the elderly man with the zhuge came to their village to do.

But with understanding came shame, especially as the zhuge’s genitals were very prominent; it drooled when excited and emanated a strong hormonal odor. According to a Miaoli County Culture and Tourism Bureau document, children often followed behind and made fun of the zhuge and the breeder.

As time went on, the term “qian zhuge” became associated with prostitution, while “zhuge” was used to chide lecherous men. Many breeders were deeply ashamed of their job, and the bureau had a hard time getting people to open up for a book on bygone professions.

Working conditions improved in the 1970s, as breeders could now transport multiple zhuge on motorized vehicles over further distances.

Huang recalls seeing a truck carrying six zhuge cruising slowly down the road, its speakers blaring love songs. Banners on the side of the vehicle indicated the breeds available: Landrace and Berkshire.

SUCCESS STORIES

Not all breeders felt ashamed about their work; some were quite proud of it.

Chen Jung-tang is among the nation’s most successful former zhuge breeders. Originally a grocery store owner, he entered the zhuge profession to pay for his children’s education. At the peak of his success he had 33 zhuge and charged NT$2,000 per session. His services were in demand across Taiwan, and he traveled up to 400km per day.

A Chinese Television Service (華視) clip from 1988 featured a Chiayi (嘉義) breeder whose eight zhuge enjoyed great popularity in the area due to their outstanding health and virility. The report noted that he was a rare case, as the industry was on its last legs.

The man charged NT$300 per session for “regular” male pigs, and NT$600 for those he especially raised to be zhuge. In the 1960s, the standard rate was just NT$50 per session and the job was much more laborious.

Then 60 years old, he told reporters that he refused to accept the decline of the industry and vowed to persist as long as he was alive.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government

Nov. 3 to Nov. 9 In 1925, 18-year-old Huang Chin-chuan (黃金川) penned the following words: “When will the day of women’s equal rights arrive, so that my talents won’t drift away in the eastern stream?” These were the closing lines to her poem “Female Student” (女學生), which expressed her unwillingness to be confined to traditional female roles and her desire to study and explore the world. Born to a wealthy family on Nov. 5, 1907, Huang was able to study in Japan — a rare privilege for women in her time — and even made a name for herself in the