Andy Warhol began his career by mocking the notion of art’s sanctimonious status and elevated value. He recycled grubby tabloid headlines, mimicked the mass-produced stock in supermarkets and called his industrially busy studio the Factory. His witty sabotage was only too successful: art enabled him to magically conjure up money, and when he died in 1987 he left an estate worth US$220 million.

After Warhol’s death, a foundation set up in his name vowed to redistribute this wealth to needy artists as well as subsidizing a reliable catalogue of his work; an authentication board was established to protect the market from proliferating fakes. The board’s judgments were issued by fiat, and in 2001 its experts ruled that a silk-screened self-portrait, which the American collector Joe Simon (also known as Joe Simon-Whelan) hoped to resell for US$2 million, had not been made by Warhol, even though it was stamped with his signature and inscribed by his business manager. Simon’s print was returned with DENIED stamped on the back in indelible red ink that penetrated the canvas and rendered it worthless.

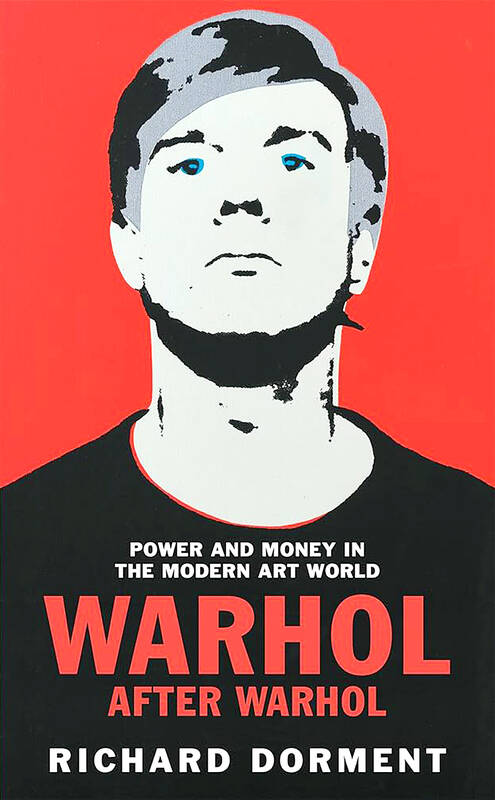

AUTHENTIC WARHOL?

No reason was given for the decision and, in frustration, Simon appealed for help to Richard Dorment, then the art critic of the Daily Telegraph. Dorment at first viewed Simon as a nuisance, but gradually came to sympathize with his quandary. Evidence overlooked by the board convinced Dorment that Simon’s print was authentic; it had been rejected and mutilated, Dorment suspected, because it contradicted the foundation’s preferred narrative about Warhol’s technical methods during different periods of his career.

As he probed further on Simon’s behalf, a related case intrigued Dorment. A collection of 44 Warhol paintings had been seized from their owner and labelled forgeries in 1991, only for the board to reconsider its decision12 years later; 35 of the erstwhile fakes were rehabilitated and resold by the foundation for millions of dollars. Jokily alluding to The Godfather, Dorment remarks that the issue of authentication had been coated with concrete, dropped in the river and left to “sleep with the fishes.”

Eight years of legal to-ing and fro-ing ended unsatisfactorily for Simon, who withdrew his claims in 2010 but remains “scalded,” Dorment says, by the saga. Although no blame attached to the foundation, changes were subsequently made to the way it handled Warhol’s estate: the authentication board closed down and, as Dorment tartly puts it, an auction house was engaged to “flog tens of thousands of works to… punters online.” The result was an indiscriminate commercial boom. In 2013, a pair of boxer shorts imprinted with a dollar sign, classified as a “novelty item” in the inventory, sold to an overeager buyer for US$16,000: so much for pop art’s subversive campaign against the overvaluation of old masters.

The print was returned with DENIED stamped on the back in indelible red ink, which rendered it worthless

The long-dead Warhol haunts Dorment’s book, a spectre in a silver fright wig who lacks “physical mass or emotional depth.” By contrast with this wispy and ineffectual ghost, the combatants who wrangle over his leavings come vividly and often fearsomely alive. Simon’s skyscraping legal expenses were covered for a time by a Russian oligarch, who tried to cheer him up by inviting him on a weekend jaunt to Latvia, travelling by private jet. Luckily, Simon did not accept: during the trip his friend, who had balked at paying a bribe of US$400 million to Vladimir Putin’s bank account in Cyprus, was abducted and killed by the Kremlin’s enforcers. Dorment also has some scurrilous fun with the CV of the foundation’s chief litigator, who previously defended mafia bosses in a murder trial and later sued his own mother for defamation.

TRUMP ANGLE

Current events supply an epilogue to the tale. Sleuthing on Google, I found that the lawyer with a mission “to destroy Simon’s credibility by annihilating his character” went on to represent Donald Trump’s business manager, who was jailed earlier this year for conspiring with his employer to evade taxes. This is not the only connection between Simon’s grievance and the tottering Trump Organization. Dorment mentions an attempt by a disgruntled collector to mount a class-action lawsuit charging the Warhol Foundation with “fraud, collusion and manipulation of the market.”

That case, like Simon’s, came to nothing, but Trump, having inflated his assets to dupe banks into making loans to him, is now on trial in New York for a similar litany of crimes. It’s only too easy to slither from technical arguments about Warhol prints to the sleazier manoeuvres of what Trump calls “the art of the deal.”

When Donald Trump Jr was called as a witness in the New York case in November, the best defence he could offer was aesthetic. He boasted that in dreaming up the lucrative wheeze of a condominium hotel his dad was “on the leading edge of creativity,” and gloated that a Trump golf club made manifest “the artistry that comes to fruition over and over.”

Dorment’s research introduces him to “a new branch of the legal profession: art law.” The conjunction between those mismatched activities is startling and not to the benefit of either. The practice of law nowadays involves playing slippery verbal games, while art, as Don Jr’s accolade proclaimed, has become synonymous with presentation and illicit pretence. Long after the event, the squabble over a silk screen swells into a parable about our morally muddled times: we are living through the bonfire of the verities.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,