There are quite probably no films anywhere in the world like those of Malaysia-born, Taiwan-based director Tsai Ming-liang (蔡明亮). Instead of subtle plots, complex characters and exotic locations you have blocks of material juxtaposed like cartoon images, an intensely autobiographical approach and the constant use of the same actors. Yet he was the first director anywhere commissioned to make a film for the permanent collection of the Louvre Museum in Paris, France’s premier museum. His films are especially revered in France.

Tsai’s short film It’s a Dream (是夢, 2007) contains in compact form his understanding of film as a dreamlike state and his reflection on the cinema as “a space so saturated with memory and queer desire that it can feel disorienting.”

Tsai was born in Kuching, Malaysia and his father is played by his “male muse,” actor Lee Kang-sheng (李康生), the narrator as a boy by Lee’s nephew, and his mother played by Tsai’s actual mother.

Tsai recalls seeing Chinese films in Malaysia as a boy, and the film is accompanied by a melancholy Mandarin pop-song. His first feature film set in Malaysia was I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone (黑眼圈, 2006).

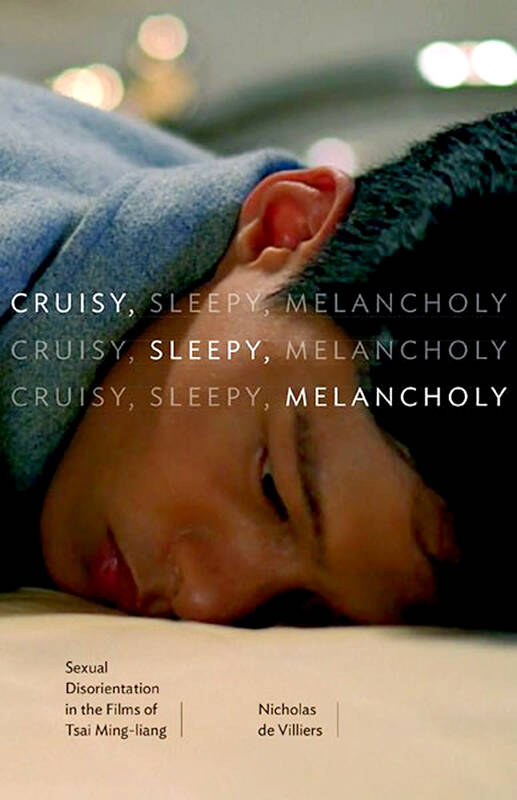

As Nicholas de Villiers writes in Cruisy, Sleep, Melancholy, It’s a Dream, which is only three minutes long, encapsulates many of the themes of Tsai’s work — melancholy, nostalgia, familial intimacy, sexual cruising, dreaming, “and both temporal and spatial disorientation.”

I have to admit the discussion of temporal and spatial was something I didn’t fully understand.

Scenes set in nearly empty cinemas proliferate, as in his 2003 film Goodbye, Dragon Inn (不散), set in an old Taipei cinema at its last ever screening. Seven or eight such Taipei cinemas have now closed.

The title of this book suggests sexual availability (“cruisy”), dreamlike states (“sleep”) and loss (“melancholy”).

Tsai came out as gay on film in 2015 in Afternoon, and his films extensively reflect Taiwanese tongzhi (same-sex orientation). His other themes include water in its many forms, old-fashioned Mandarin pop-music, minimal spoken dialogue and non-normative forms of sexuality.

Tsai arrived in Taiwan in 1977 at the age of 20 as a student of drama and cinema. Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) had died two years earlier, in 1975, and massive changes were underway.

The influence of Andy Warhol is noted, as are Japanese and French influences in the films set in those countries.

The author begins his more detailed analysis by looking at two early films, Vive L’Amour (愛情萬歲, 1994) and I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone. Both appear related to Tsai’s “porn musical,” The Wayward Cloud (天邊一朵雲, 2005).

Nicholas de Villiers is a professor of English and film at the University of Norh Florida. The frequent presence in his text of critical theorists such as Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, Eve Sidgwick and chef d’ecole Jacques Derrida will tell some readers what to expect.

Tsai once said he was “sick of people labelling my films as ‘gay films,’” but gay a huge number of them are. This is a notably gay-friendly book as well, with phrases such as “homophobic cultural logic” proliferating. It starts with a quotation from Marcel Proust. No No Sleep (2015) was “mistaken for gay porn by some YouTube users.”

Tsai, however, prefers to say he sees people as lonely and “existing in their own solitude.” Looked at another way, in The Hole (洞,1998) he “hybridizes two genres — the disaster film and the musical — in a way that is deliberately disorienting” (the author).

If “metacinema” means films that constantly draw attention to the fact that they are fictional creations and not reality, there can be no one in the world of film more “metacinematic” than Tsai Ming-liang.

In Rebels of the Neon God (青少年哪吒, 1992), one of the Taipei Trilogy, a poster featuring James Dean, the sexually ambiguous rebel without a cause, appears as another metacinematic gesture, as pointing directly to one’s artistic antecedents must necessarily be.

Ancient cinemas, rest-rooms, old songs and the nostalgia they bring with them, bathhouses, the “pre-AIDS golden age of hustling” are all frequent themes or locations.

Afternoon is a long talk with Lee Kang-sheng. Stray Dogs (郊遊, 2013) is set in Taichung. There was also Stray Dogs in the Museum (2015) shown in the Museum of National Taipei University of Education in which multiple overnight screenings of Stray Dogs are shown with audience members in sleeping bags.

Tsai’s films take place in Taipei, Kaohsiung, Taichung, Paris, Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Marseilles and Tokyo (where the location is made specific).

There is some hostile criticism in this book, notably quoted from Tony Rayns. He argues that Tsai “plows one furrow a little too often.” No other film director has returned so compulsively to the same themes, the same images, the same actors and the same tragi-comic tone, he says.

Rayns also comments that scenes are often single shots, with no causal link between one and the next. You don’t, in other words, need to be gay to find Tsai’s films disorientating.

Dreams, cinemas, sleepiness, extreme stylization — seen here as part of this hostile criticism, are nonetheless extensively useful when thinking through this body of work and trying to arrive at a balanced evaluation.

Despite an international following, Tsa’s films are many of them strongly Asia-centered. As Tsai himself commented in 2013: “The fast-paced and Western-influenced development of Asian cities gives me the feeling that we are in a state of constant anxiety and uncertainty, as if we were drifting without any solid foundation beneath us.”

He nonetheless finds Taiwan a genuine home, and for a time — maybe still — he lived in the hills with Lee Kang-sheng.

The latest Tsai film mentioned in this book is Days (日子, 2020), a post-retirement feature-length movie.

Finally, a friend has said there are too many books now on Taiwanese film directors. Why not more on scientists, archaeologists and thinkers?

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move

Stepping off the busy through-road at Yongan Market Station, lights flashing, horns honking, I turn down a small side street and into the warm embrace of my favorite hole-in-the-wall gem, the Hoi An Banh Mi shop (越南會安麵包), red flags and yellow lanterns waving outside. “Little sister, we were wondering where you’ve been, we haven’t seen you in ages!” the owners call out with a smile. It’s been seven days. The restaurant is run by Huang Jin-chuan (黃錦泉), who is married to a local, and her little sister Eva, who helps out on weekends, having also moved to New Taipei