Aug. 25 to Aug. 31

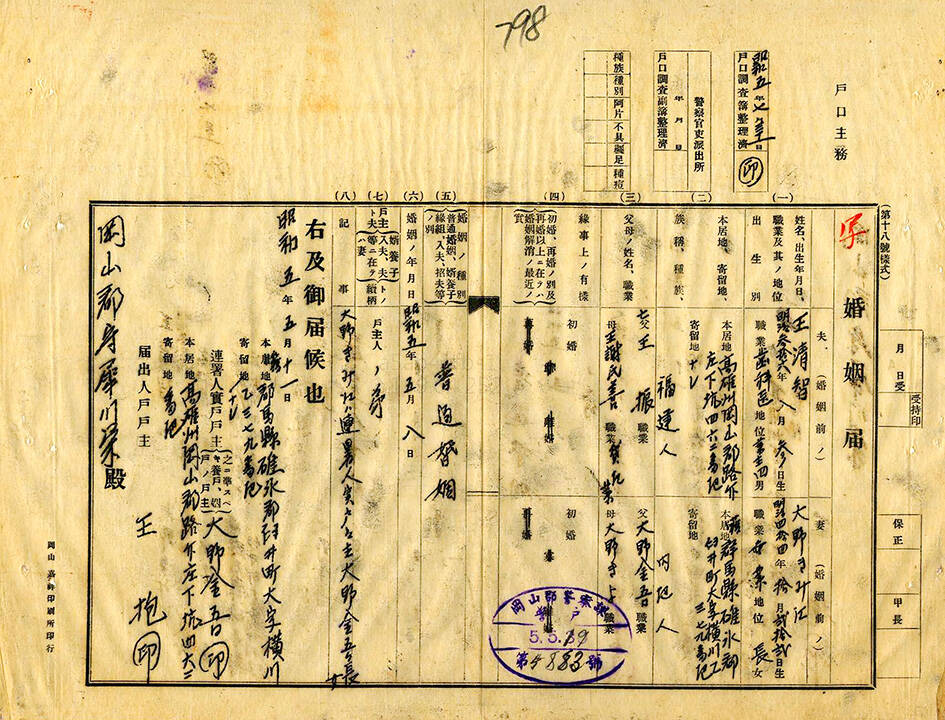

Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household.

In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized, and our children considered illegitimate — how can any parent bear this?”

Photo courtesy of Open Museum

“Taiwanese are indeed Japanese citizens — so why this discriminatory treatment regarding our status? This not only contradicts the goal of assimilation, but it leaves the three million Taiwanese uncertain of what it means to be Japanese nationals.”

The main obstacle was the fact that Taiwanese did not fall under the Japanese koseki (family registry) system. A Taiwanese spouse could be entered into a Japanese registry, but not the other way around.

The government took Lin’s case seriously, as it contradicted their new colonial policy of “homeland extension,” which sought to apply Japanese laws to the colony and promote assimilation.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

On Aug. 25, 1920, the Provisional Law for Japanese-Taiwanese Intermarriages went into effect. Yet, without a Taiwanese family registry system, bureaucratic hurdles persisted until 1933, when Taiwanese were finally granted one.

TOOL FOR ASSIMILATION

Yukie Tokuda, Yang Pei-wen (楊裴文) and Liao Yuan-chun (廖苑純) each offer detailed studies of intermarriage during the colonial era.

Photo courtesy of Library of Taiwan Historica

Until the 1920s, Japanese and Taiwanese communities remained largely segregated, living in separate neighborhoods and attending different schools. All governors up to this point were military men, and colonial rule was focused on subjugation and control. It wasn’t until 1915 that most Indigenous areas were brought under Japanese control, and the last major Han Taiwanese rebellion was suppressed.

Even so, there was some intermarriage. A 1912 survey showed 12 legal marriages between Japanese men and Han Taiwanese women, with 147 unregistered cohabitations. Although illegal, 38 Taiwanese men lived with Japanese wives. There were also 21 unofficial unions between Japanese men and Indigenous women, often political marriages between officials and relatives of Indigenous leaders.

Things began to change after World War I, and Japan shifted its colonial policy toward integrating Taiwanese as loyal Japanese subjects. However, implementation was limited and uneven.

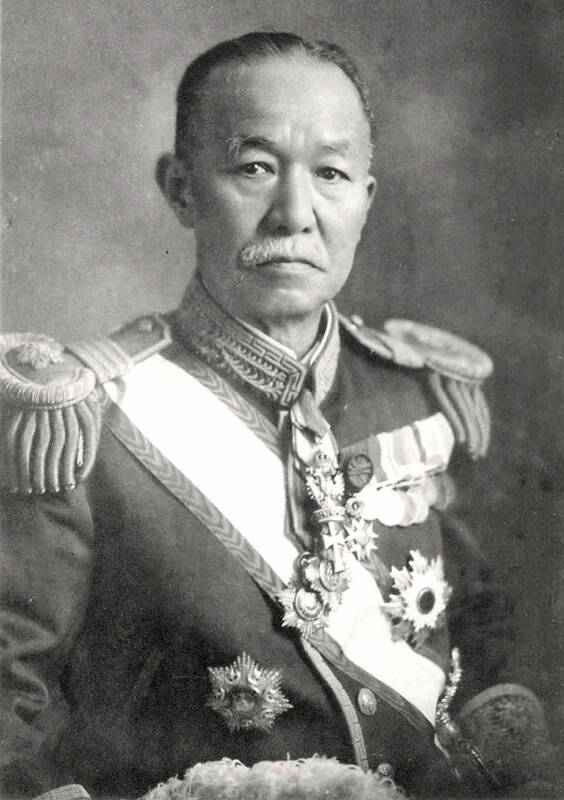

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In 1919, Japan appointed Taiwan’s first civilian governor-general, Kenjiro Den, who announced in a meeting regarding homeland extension: “The most effective way to foster social integration is surely through marriage. Yet the law allows unions between Japanese and foreigners, but not between two subjects of the empire. That is a grave oversight.”

Critics pushed back, warning that intermarriage would “dilute” Japanese blood or doubting whether a small Japanese minority could assimilate the Taiwanese majority through marriage.

“If the governor-general’s office is so confident, they should set an example and marry their children to Taiwanese,” scholar Ren Shibata said.

Despite it often being brought up in official rhetoric, the government never actively promoted intermarriage, allowing it to occur naturally.

TAIWANESE HUSBAND, JAPANESE WIFE

After the 1920 law passed, marriages between Taiwanese men and Japanese women soon outnumbered the reverse, surging through the 1930s and 1940s. Yang’s census data shows 361 such marriages between 1905 and 1942, compared to 128 Japanese male-Taiwanese female unions. The first marriage between an indigenous male and Japanese female appeared in 1928. These numbers differ from report to report; another suggests that there were 800 mixed couples in 1944.

Unregistered marriages were likely far more common, albeit still a small fraction of the population. Japanese in Taiwan generally maintained a sense of superiority and integration was limited.

Many Japanese men who came to Taiwan could not afford to pay the hefty bride price for a Taiwanese wife, often choosing to cohabit with her instead. Those with means typically preferred Japanese wives. Furthermore, Tokuda writes that Han Taiwanese families were more accepting of sons marrying Japanese wives as their identity remained with the husband; daughters who did so would become Japanese, as well as her children.

By contrast, the majority of Taiwanese men who married Japanese women were from wealthy backgrounds. Starting from 1920, a growing number of Taiwanese headed to Japan to study due to limited options for higher education back home. Free from family constraints and gender segregation in Taiwan, and exposed to Western ideals of free marriage, they often dated and married Japanese women, later bringing them back to Taiwan — often to their families’ dismay. These couplings were more common than those formed in Taiwan itself, Liao writes.

MODEL COLONIAL SUBJECT

The media seemed to encourage such marriages, believing they would aid assimilation. The state-run Taiwan Daily News even ran a 10-part series on these couples. Yet reports show many Japanese wives adopted Taiwanese customs, and Japanese husbands who came to Taiwan alone often did the same.

Curiously, newspaper features focused almost entirely on Taiwanese male-Japanese female marriages. Liao suggests that wealthy, Japanese-educated Taiwanese husbands better fit the “model colonial subject” that the government wanted to showcase. Tokuda writes that perhaps the Japanese didn’t actually wish for widespread intermarriage — they just wanted these elites to marry Japanese to bind them more tightly to the regime.

During this time, the Japanese government still couldn’t figure out what to do about the Taiwanese family registry, remaining reluctant to grant them full citizenship privileges.

Finally on March 1, 1933, with the creation of a Taiwanese family registry system, all Japanese-Taiwanese marriages were fully legalized. There were still limitations, as Taiwanese couldn’t transfer their registry to Japan, a restriction that lasted until the end of colonial rule.

Next week’s feature will examine the lives of mixed couples, how they chose to live and raise their children, and the many challenges they faced.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted