When Monika Keating was laid to rest in 2019, her widower Jerome opted to have most of her ashes buried at a designated flowerbed in a public cemetery on Yangmingshan, without a headstone or any other type of marker. Monika’s other cremains were scattered or placed at locations which had meant a great deal to her during her lifetime.

Jerome Keating, who moved to Taiwan from Texas in 1988, recalls that he didn’t hesitate to choose a green alternative to renting a niche for her ashes in one of Taiwan’s many columbaria. These structures, which often resemble pagodas, are purpose-built for the storage of cremation urns.

Monika’s family offered a space in a mausoleum, but he turned it down.

Photo courtesy of Jerome Keating

“I take the view that our bodies are vessels of our spirit or soul or whatever one wants to call it. We’re children of the universe, and our bodies as physical matter are part of that,” says Keating, a business consultant, author and academic.

When he learned that the Taipei City Government provides environment-friendly options for cremated remains, such as burying them beneath newly-planted trees or beside flowerbeds, he quickly chose the latter, “since Monika always liked flowers.”

He was then shown several different sites, each big enough for dozens of green burials.

Photo: Chang Ching-ya, Taipei Times

“I chose one which had a fine view. Symbolically, I felt that Monika’s spirit could both freely roam the mountains from there and always have a nice view. Once the decision had been made, the ashes were brought up to Yangmingshan Zhenshan Garden (陽明山臻善園), and one of the workers went with me and some family members. He dug a small hole in the designated area and we poured in the ashes,” says Keating, who speaks highly of the city’s management of the procedure.

Keating encountered little resistance from friends and family.

“My mind was already pretty well made up,” he says.

Photo: Steven Crook

Suggestions that disposing of Monika’s ashes in this way might be disrespectful or unhygienic — or that there was a danger a typhoon could wash everything down the mountainside — had little sway over him, he explains.

GREEN BURIAL

Green-burial procedures make both financial and environmental sense, Keating says. The cost is very reasonable, “and it makes little sense to dedicate so much land to putting caskets six feet under when cities and towns are running out of space.”

Photo: Cheng Ming-hsiang, Taipei Times

Few Taiwanese are buried these days — the country’s cremation rate (96.3 percent in 2017) is one of the highest in the world — yet graveyards are ubiquitous. This is because the crematorium-to-columbarium SOP is relatively new.

As recently as 1986, fewer than one in five citizens was cremated. The paradigm shift in funeral practices that coincided with Taiwan’s democratization was encouraged by government officials and the media.

In 1977, China Times, one of Taiwan’s Chinese-language newspapers, pointed out that if every deceased person was allotted a modest 2 ping (6.6 square meters) for their tomb, the country’s cemeteries would expand by 47 hectares per year. By way of comparison, Taipei’s Daan Forest Park (大安森林公園) covers 26 hectares.

Photo: Steven Crook

“The living and the dead will compete for land,” the newspaper predicted.

Since then, the annual number of deaths has almost tripled to around 200,000, and municipal columbaria are running out of space. According to a story in CommonWealth magazine last month, those in Taipei are already more than 90 percent full. Because so many people are death-phobic, finding locations for new columbaria is almost as difficult as expanding graveyards, and perhaps even more challenging than building new prisons.

The eco-friendly burial of cremains was given a legal basis in 2002. At the same time, the Ministry of the Interior began providing subsidies to local governments willing to promote these new funeral practices.

Initial progress was slow. In 2012, the number of green burials was just 1,765, or 1.15 percent of all deaths. But last year, more than one in nine funerals was followed by an interment of ashes like that arranged for Monika Keating. As CommonWealth points out, environmentally-friendly ceremonies are now far more common than traditional burials.

A section of Fude Public Cemetery (富德公墓) in Taipei’s Wenshan District (文山) was one of the first sites in Taiwan to permit “tree burials.” Next of kin may choose any vacant lot and take part in the digging. Ashes are laid to rest in biodegradable bags. Because each place of interment is eventually reused, these memorial gardens and woodlands shouldn’t ever run out of space.

Among prominent Taiwanese laid to rest in this way was Sheng Yen (聖嚴, 1931-2009), founder of Dharma Drum Mountain (法鼓山, DDM), one of the country’s largest Buddhist organization. His ashes were interred in the Eco-Friendly Memorial Garden, part of the DDM complex in New Taipei City’s Jinshan District (金山).

Other death traditions are also bad for the environment. The burning of joss paper during funeral rites generates air pollution. The customary tidying of graves around Tomb Sweeping Festival results in numerous fires in rural and semi-rural areas.

A press release by Taipei City Government in April 2017, reporting on Tomb Sweeping Day activities, reiterated official support for “all kinds of funeral types that help minimize the impact on the environment, be it tree, flower or sea burials.”

This wording, which appears on the city’s English-language Web site, is somewhat misleading. Unlike Australia, the US and the UK, all of which allow non-emergency burials at sea at certain locations, Taiwan’s law doesn’t permit the disposal of uncremated corpses at sea.

Residents of nine of Taiwan’s 22 counties and cities, among them Taipei and New Taipei City, can apply to deposit human ashes in the ocean. The authorities make all the arrangements, but this has yet to become a popular option. In most years, fewer than 50 sets of cremains are consigned to the depths.

The growing popularity of flowerbed and tree burials is encouraging, but current rules stand in the way of those who might opt to have their body disposed of by an even greener method.

AQUAMATION

Neither human composting, nor what’s called water cremation and aquamation are permitted by the Mortuary Service Administration Act, the Ministry of the Interior confirmed via e-mail on Nov. 13.

The carbon footprint of a conventional cremation is roughly equal to that of driving a gasoline-powered car 900km. Aquamation is far more energy efficient, requiring between one tenth and one quarter as much electricity.

Aquamation involves placing the corpse in a pressurized metal cylinder that contains a mix of water and strong alkali. This is heated to 160 degrees Celsius; within a few hours, everything except the bones and teeth are liquefied. These solid remains are ground into powder and handed to relatives to handle as they see fit.

The liquid remains are safe for immediate disposal through the sewer system, which is why the process makes many people uneasy. Who wants a loved one to be poured down the drain? Supporters point out that the liquid can also be given to the family, who may use it to water flowers bought to memorialize the deceased.

Aquamation is legal in more than half of the states of the US, but it accounted for fewer than 0.1 percent of all cremations in the country in 2021, Time reported in March last year.

Human composting — which is even better for the planet in terms of carbon footprint — is possible in a mere five states, soon to be joined by Nevada and California. It is also legal in Sweden.

The process involves sealing the corpse in straw and other natural materials, then letting nature take its course. Seattle-based funeral home Recompose says they use “the principles of nature to transform our dead into soil… The biological process mimics the earth’s natural cycles and is similar to what occurs on the forest floor as organic material decomposes and becomes topsoil.”

Asked for his opinion about these newer methods, Keating says he doesn’t know much about them. Referencing a 1973 science-fiction movie that depicts a polluted and hungry dystopia in which corpses are processed into food for humans, he quips: “They make me think of Soylent Green.”

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

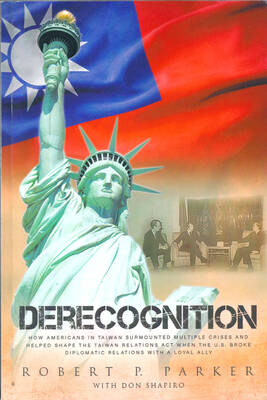

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any