Nancy Chen Baldwin was born Lai Shui-yun (賴水雲) in 1950 in a crude, concrete farmhouse on Taiwan’s north coast near what is now New Taipei City’s Shimen Township. Then at the age of five, she was sold as a chambermaid to a Taipei prostitute, Grace Chen, who worked bars from Keelung to Kaohsiung frequented by American GIs and merchant marines.

According to age-old Chinese custom, Grace, an uneducated freelance bar girl who was unable to bear children of her own, was buying a surrogate daughter, whose life she would control and who would care for her in old age.

Baldwin, who is now 73, would eventually go on to achieve status as a senior administrator in the US aerospace industry during a 40 year career. But despite her success, she always struggled to find a sense of identity and belonging, caught between her birth family, adoptive mother and self-made American reality. She was also haunted by doubts of self worth after literally being sold as chattel in her youth for the price of one hundred American dollars.

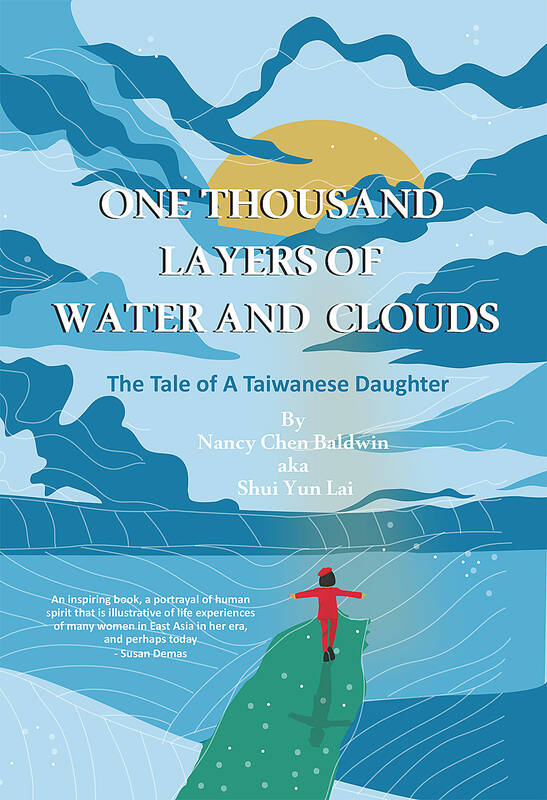

Her life story, now related in a new memoir, One Thousand Layers of Water and Clouds, is as rich and turbulent as its vast transitions — during the decade of the 1960s, she literally teleports from a Taiwanese farming village where she’s entertained by roadside operas to a Western nuclear family gathered around a television set to watch Lawrence Welk — as any related by that preeminent chronicler of the Asian-American story, Amy Tan. One could easily imagine her as a fifth member of the Joy Luck Club.

In telling her story, Baldwin’s motivations overlap with Tan’s in many ways. Chief among them is the desire to untangle histories of personal trauma, of a life torn by cultural and historical schisms, and find one’s place in the world. Her story truly is remarkable and valuable, especially as there are so few accounts of the lives of Taiwanese women in English.

But Baldwin, a first time author, also admits that she is in part writing an autobiography as therapy and a way to reconcile with an unsettled past. While there is great strength in the larger portion of her narrative, some segments are overly sentimental, and the prose is for the most part merely functional.

Yet as an immigrant’s fable, Baldwin’s story is rich indeed, and in a literary sense, the narrative is extremely well constructed.

Baldwin was originally sold by her parents to pay off a debt. Her birth parents were farmers who couldn’t support a family on a small patch of land, so they borrowed money from their parents to start a business peddling fruit from a cart on street corners in Taipei.

CHAMBERMAID YEARS: IDENTITY CRISIS

The venture quickly failed, and Baldwin’s parents were reduced to working lowly construction jobs, recycling bricks and wood from demolished buildings. Baldwin recalls pitch black nights living in mobile tent cities of laborers, pell-mell collections of tarps and bamboo poles which clustered around building sites.

While Baldwin’s parents literally scraped the dirt to rebuild postwar Taipei, her grandmother, eager for repayment on her loan, was pushing to sell her granddaughter. The buyer she found was the bar girl and “substitute wife” Grace Chen, who rich with the US dollars of American servicemen, could afford the luxury of a chambermaid.

With Baldwin’s sale, enacted through a sort of feudal contract between families, Baldwin’s surname changed from Lai to Chen. It was her first of many name changes and source of an identity crisis which would stretch deep into Baldwin’s life.

Baldwin is not able to tell us much about the bar girl’s life of her new surrogate mother. She was far too young and was kept at a safe distance from this nighttime world. We only learn that Grace worked mainly on Zhongshan North Road in Taipei, where she bought a three-bedroom apartment in the early 1960s.

Though Grace was the chief breadwinner for her extended family, the source of her income was taboo. Even after Grace’s death in 2013 (she was buried in Palo Alto, California), this period of her life was never spoken about, always remaining a dark family secret.

For the most part, Grace was an absentee parent, foisting care of young Shui-yun onto the families of younger brothers or else her blind mother, who tended a temple in a farming village in Taoyuan.

To many Taiwanese at that time, bar girls like Grace were considered to have “betrayed their race.” Often, such women became “substitute wives,” who were kept for months at a time as live-in companions with American GIs in Taiwan on two-year postings.

Baldwin eventually came to see Grace as a heroine, who bore the yolk of providing for her family in dire circumstances. Grace’s clan was originally from Keelung, but after her father vanished, her mother lost her sight (owing to what is now a treatable infection), and her older sister married, Grace, at the age of 15, became the head of the household and chief provider for a family of five. Of the options available to her, she chose the bars of Taipei.

For Taiwan’s bar girls of the 1950s and early 1960s, Baldwin writes, the US was envisioned as a “magical land where the streets were paved with gold” and the “ultimate goal for most Taiwanese substitute wives.”

Grace achieved this dream shortly before Baldwin’s 14th birthday, when she announced she was marrying a merchant marine and they were moving to America.

US YEARS: DESTINY

When they arrived in 1964 in San Jose, California, Baldwin, upon seeing her passport for the first time, discovered that she now had an English name, Nancy Kerr, and that she had been legally adopted by Grace’s new husband, William Kerr. It is one of many existential shocks from this early phase of her life.

Grace was meanwhile in for a shock of her own when her vision of America as a land of gold quickly shattered. Kerr had wooed her with stories of a house, a fat savings account and promises that he would leave the seafaring life to settle down. What she discovered upon arrival however was that Kerr lived with his mother, had been previously married, paid most of his earnings in alimony and would continue to absent himself for months at a time on ocean voyages.

Within two short years Grace and Kerr divorced. To survive, Grace took jobs doing manual labor alongside Mexican immigrants, first in a cannery and later picking strawberries. At the same time, she sought to rekindle an old flame with a US air force man with whom she’d been secretly trading letters for almost 15 years.

Baldwin meanwhile enrolled in American high school, dove into her studies, worked part time jobs, won scholarships and began clawing her way towards control of her own destiny.

As Baldwin gained her independence, however, she also widened an already yawning chasm between herself and Grace. For decades to come, Grace, who never learned to speak other than an accented, broken English and felt too insecure to become an American citizen, will berate Baldwin, her erstwhile chambermaid, as ungrateful for her motherly sacrifices and for betraying the lifelong promises implied in Baldwin’s purchase.

The transposition of this kind of feudal belief system onto modern times is perhaps the most salient instance of the generational upheavals that occurred during Baldwin’s lifetime. But her memoir is in fact full of them. One of the more amusing examples is a traffic ghost in Taipei’s Ren-Ai Circle that Baldwin believes has it in for her.

Presently 73, Baldwin’s generation of Taiwanese still very much has a say in the world, controlling much of the nation’s wealth and, in the US, standing as the foundation of a Taiwanese-American community. One of the more mind boggling take-aways from Baldwin’s memoir is how this generation was in fact born of the feudal farmstead and then navigated a path to global modernity.

This sweeping scope, in combination with a wealth of personal detail and unvarnished honesty, is the appeal of Baldwin’s memoir. One imagines that it will speak to a much wider Taiwanese readership, as there were many, many others who shared this generational journey.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall