July 28 to Aug. 3

Former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly maintained a simple diet and preferred to drink warm water — but one indulgence he enjoyed was a banned drink: Coca-Cola.

Although a Coca-Cola plant was built in Taiwan in 1957, It was only allowed to sell to the US military and other American agencies. However, Chiang’s aides recall procuring the soft drink at US military exchange stores, and there’s also records of the Presidential Office ordering in bulk from Hong Kong.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

By the 1960s, it wasn’t difficult for those with means or connections to obtain Coca-Cola from the black market. It was also available at high-end restaurants and bars catering to US soldiers. Despite its relatively low price, it was seen as a luxury item and symbol of American consumer culture for Taiwan’s upper class.

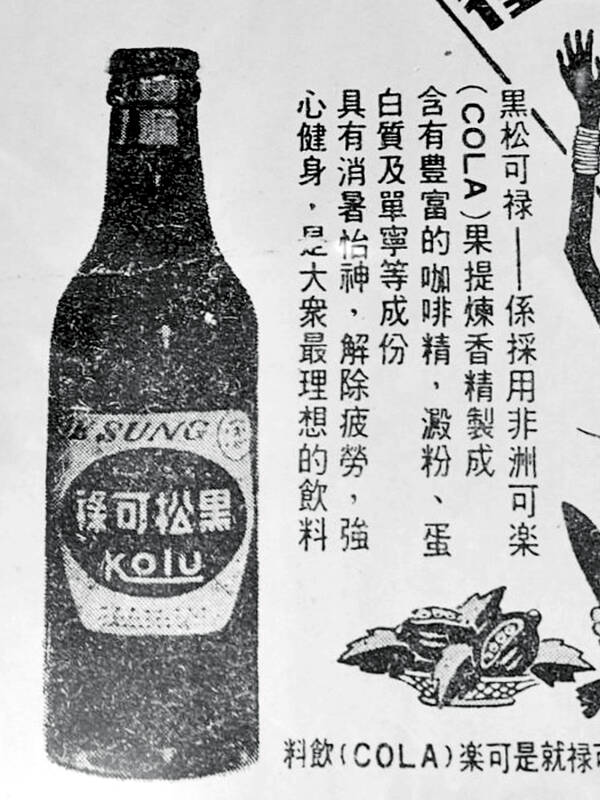

For regular citizens, who were exposed to American pop culture through Hollywood movies and other media, “the ‘Coca-Cola dream’ remains a dream,” a United Daily News op-ed stated. There were many local imitations such as Hey-Song Kolu — the Chinese term for cola, (kele, 可樂) was trademarked then.

“Although the taste differed and the quality was inconsistent, for those who had never tried Coca-Cola, these imitations fulfilled the social desire to emulate the act of drinking American soda,” writes Tseng Ping-chang (曾品滄) in “Taste of America: The ban on Coca-Cola in Taiwan during the early Cold War” (美國的滋味:冷戰前期臺灣的可口可樂禁令與消費).

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

However, with smuggled Coca-Cola flooding the market and draining tax revenue, plus mounting pressure from international soda companies, the government caved in 1966 — with the condition that Coca-Cola give up their trademark on “cola” and allow local partners to hold up to a 20 percent stake in the operation.

On July 28, 1968, Coca-Cola finally hit Taiwan’s store shelves, with countless other American goods to follow.

BANNED COMMODITY

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

Even though Coca-Cola was sold in both Japan and China before World War II, there’s no evidence of it entering the Taiwanese market. Tseng writes that the only mention of the drink was from a letter in 1911 noting the US Consulate in Taiwan’s order of 10 gallons of Coca-Cola from company headquarters in Atlanta.

The US presence in Taiwan grew during the Korean War, pledging military and economic aid as part of its campaign to oppose communism in East Asia. US military consultants began arriving in May 1951, and to meet their needs, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) authorized the Taiwan Trading Company to import and distribute Coca-Cola to American personnel.

When the Provincial Supplies Management Committee proposed importing 5,000 cases to be sold through the Tobacco and Alcohol Monopoly Bureau, then-provinicial governor Chen Cheng (陳誠) blocked the plan. He argued that importing non-essential consumer goods violated wartime austerity policies and wasted precious foreign exchange.

Photo courtesy of Chang Chien-hsi vis Flickr

Local soda manufacturers strongly supported the ban. There were about 110 soft drink factories in Taiwan, mostly small, family-run operations. Only two larger-scale operations, including Hey-Song, had the capacity to supply the entire island.

By the mid-1950s, there were about 3,600 US personnel in Taiwan, many with families. To reduce shipping costs, in 1957 the Sino-American Soda Factory (中美汽水廠) was established in today’s Sijhih District (汐止) in New Taipei City. Although it enjoyed tax exemptions, the government still refused to allow it to sell to the general public.

‘NON-ESSENTIAL CONSUMER PRODUCT’

Photo courtesy of Veteran Affairs Council

With Japan lifting its ban on Coca-Cola in 1956, South Korea and Taiwan became the only US allies in East Asia to continue restricting the beverage. Despite Taiwan’s reliance on US aid, the government resisted the import of many American products.

Tseng writes that Taiwan was in no economic condition to allow such imports during the 1950s. The population surged with refugees from China, while agricultural and industrial production was disrupted during World War II. Massive defense spending further strained finances, leading to serious inflation, foreign exchange shortages and national debt.

The government’s priority was to stabilize prices and develop local industry, strictly reviewing and controlling imports and exports. It mostly targeted goods already produced domestically or “luxury items.” Coca-Cola was deemed a “non-essential consumer product” with “little benefit to public health” — even with the factory, they still had to import the soda’s concentrate from the US, which would consume scarce foreign exchange.

Photo Courtesy of Yahoo Auctions

In 1952, foreign affairs minister Chang Tzu-kai (張茲闓) stated that while Taiwan welcomed foreign investment in industrial or mining enterprises, “if the investment is merely for personal enjoyment or to increase consumerism, we truly cannot accept it.”

The domestic beverage industry was also a key concern. Soda production was viewed as an important civilian industry, Tseng writes, and the government taxed it up to 40 percent, making it an important revenue source. Japan’s local industry crashed after Coca-Cola’s arrival, and the government cited it as justification to turn down Coca-Cola’s repeated requests.

Also, the government wanted to instill austerity measures not just for economic purposes, but to maintain a sense of wartime urgency and focus public attention on the national goal of retaking China.

“Under this mindset, Coca-Cola, seen as a symbol of indulgence and American consumerism, was naturally regarded as dangerous and inappropriate for Taiwanese consumption,” Tseng writes.

SODA RUSH

As Taiwan’s economy improved in the 1960s, it no longer needed to rely on US aid. This gave the US and Coca-Cola more leverage to push for market access.

James Farley, a prominent Democratic politician-turned-Coca Cola Export Corporation chairman, first met Chiang in China in 1946 and maintained ties with him, visiting Taiwan twice. In 1962, he sent a letter urging Chiang to lift the ban.

The request was seriously considered by the Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Ministry of Finance and the Foreign Trade Review Committee. Although they concluded that the matter required further study, the report noted: “At present, Coca-Cola smuggled in through [US military base stores] is already widespread, affecting national tax revenue. Therefore, continuing to prohibit its sale may no longer be appropriate.”

Many profited off this black market trade of restricted US goods; even the Ambassador of Jordan was accused of partaking in 1961.

Other soda companies were also knocking on Taiwan’s doors: Pepsi visited in 1964 with legal consultant (and future president) Richard Nixon, and RC Cola visited in 1966. RC was the first to be approved, partnering with the Veterans Affairs Council — headed by then-minister of national defense Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國).

In addition to Farley’s influence, Coca-Cola partnered with prominent, well-respected locals. In 1964, the soda factory was reorganized as the Taiwan Soda Factory, under Lan Min (藍敏), Chen Chi-ching (陳啟清) and Koo Cheng-fu (辜振甫). Lan recalls in an oral history interview that she spent 15 exhausting months lobbying various government offices before the ban was lifted in May 1966.

It’s said that Coca-Cola aimed to wipe out its main rival Hey Song within five years. That never happened. Hey Song held its ground by upgrading production techniques, introducing attractive packaging and smart advertising campaigns.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an