Building a robot that’s both human-like and useful is a decades-old engineering dream inspired by popular science fiction.

While the latest artificial intelligence craze has sparked another wave of investments in the quest to build a humanoid, most of the current prototypes are clumsy and impractical, looking better in staged performances than in real life. That hasn’t stopped a handful of startups from keeping at it.

“The intention is not to start from the beginning and say, ‘Hey, we’re trying to make a robot look like a person,’” said Jonathan Hurst, co-founder and chief robot officer at Agility Robotics. “We’re trying to make robots that can operate in human spaces.”

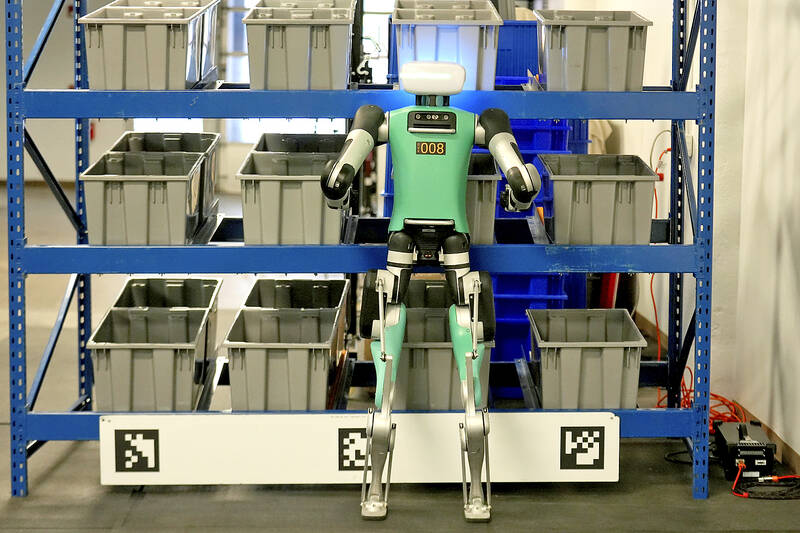

Photo: AP

Do we even need humanoids? Hurst makes a point of describing Agility’s warehouse robot Digit as human-centric, not humanoid, a distinction meant to emphasize what it does over what it’s trying to be.

What it does, for now, is pick up tote bins and move them. Amazon announced last month it will begin testing Digits for use in its warehouses, and Agility opened an Oregon factory in September to mass produce them.

NAVIGATING HUMAN SPACES

Photo: AP

Digit has a head containing cameras, other sensors and animated eyes, and a torso that essentially works as its engine. It has two arms and two legs, but its legs are more bird-like than human, with an inverted knees appearance that resembles so-called digitigrade animals such as birds, cats and dogs that walk on their toes rather than on flat feet.

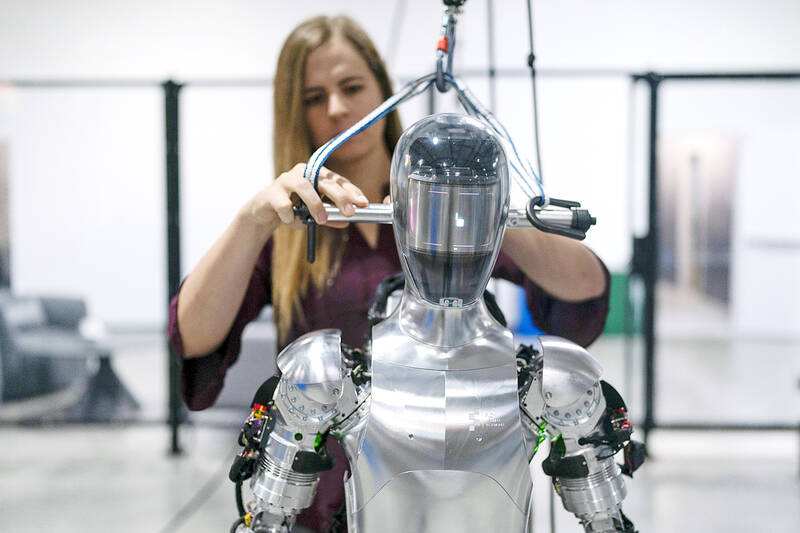

Rival robot-makers, like Figure AI, are taking a more purist approach on the idea that only true humanoids can effectively navigate workplaces, homes and a society built for humans. Figure also plans to start with a relatively simple use case, such as in a retail warehouse, but aims for a commercial robot that can be “iterated on like an iPhone” to perform multiple tasks to take up the work of humans as birth rates decline around the world.

“There’s not enough people doing these jobs, so the market’s massive,” said Figure AI CEO Brett Adcock. “If we can just get humanoids to do work that humans are not wanting to do because there’s a shortfall of humans, we can sell millions of humanoids, billions maybe.”

Photo: AP

At the moment, however, Adcock’s firm doesn’t have a prototype that’s ready for market. Founded just over a year ago and after having raised tens of millions of dollars, it recently revealed a 38-second video of Figure walking through its test facility in Sunnyvale, California.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk is also trying to build a humanoid, called Optimus, through the electric car-maker’s robotics division, but a hyped-up live demonstration last year of the robot’s awkwardly halting steps didn’t impress experts in the robotics field. Seemingly farther along is Tesla’s Austin, Texas-based neighbor Apptronik, which unveiled its Apollo humanoid in an August video demonstration.

All the attention — and money — poured into making ungainly humanoid machines might make the whole enterprise seem like a futile hobby for wealthy technologists, but for some pioneers of legged robots it’s all about what you learn along the way.

“Not only about their design and operation, but also about how people respond to them, and about the critical underlying technologies for mobility, dexterity, perception and intelligence,” said Marc Raibert, the co-founder of Boston Dynamics, best known for its dog-like robots named Spot.

Raibert said sometimes the path of development is not along a straight line. Boston Dynamics, now a subsidiary of carmaker Hyundai, experimented with building a humanoid that could handle boxes.

“That led to development of a new robot that was not really a humanoid, but had several characteristics of a humanoid,” he said via an emailed message. “But the changes resulted in a new robot that could handle boxes faster, could work longer hours, and could operate in tight spaces, such as a truck. So humanoid research led to a useful non-humanoid robot.”

ENDEARING APPEARANCE

Some startups aiming for human-like machines focused on improving the dexterity of robotic fingers before trying to get their robots to walk.

Walking is “not the hardest problem to solve in humanoid robotics,” said Geordie Rose, co-founder and CEO of British Columbia, Canada-based startup Sanctuary AI. “The hardest problem is the problem of understanding the world and being able to manipulate it with your hands.”

Sanctuary’s newest and first bipedal robot, Phoenix, can stock shelves, unload delivery vehicles and operate a checkout, early steps toward what Rose sees as a much longer-term goal of getting robots to perceive the physical world to be able to reason about it in a way that resembles intelligence. Like other humanoids, it’s meant to look endearing, because how it interacts with real people is a big part of its function.

“We want to be able to provide labor to the world, not just for one thing, but for everybody who needs it,” Rose said. “The systems have to be able to think like people. So we could call that artificial general intelligence if you’d like. But what I mean more specifically is the systems have to be able to understand speech and they need to be able to convert the understanding of speech into action, which will satisfy job roles across the entire economy.”

Agility’s Digit robot caught Amazon’s attention because it can walk and also move around in a way that could complement the E-commerce giant’s existing fleet of vehicle-like robots that move large carts around its vast warehouses.

“The mobility aspect is more interesting than the actual form,” said Tye Brady, Amazon’s chief technologist for robotics, after the company showed it off at a media event in Seattle.

Right now, Digit is being tested to help with the repetitive task of picking up and moving empty totes. But just having it there is bound to resurrect some fears about robots taking people’s jobs, a narrative Amazon is trying to prevent from taking hold.

Agility Robotics co-founder and CEO Damion Shelton said the warehouse robot is “just the first use case” of a new generation of robots he hopes will be embraced rather than feared as they prepare to enter businesses and homes.

“So in 10, 20 years, you’re going to see these robots everywhere,” Shelton said. “Forever more, human- centric robots like that are going to be part of human life. So that’s pretty exciting.”

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,