The US will spend more than US$750 billion over the next decade to revamp nearly every part of its aging nuclear defenses. Officials say they simply can’t wait any longer — some systems and parts are more than 50 years old.

For now, it’s up to young military troops and government technicians across the US to maintain the existing bombs and related components. The jobs are exacting and often require a deft touch. That’s because many of the maintenance tasks must be performed by hand.

The Associated Press was granted rare access to nuclear missile bases and weapons production facilities to see how technicians keep the arsenal working while starting the government’s biggest nuclear overhaul since the Cold War.

Photo: AP

This is how they do it and who they are:

SHAKE, RATTLE AND ROLL

Because the US no longer conducts explosive nuclear tests, scientists are not exactly sure how aging warhead plutonium cores affect detonation. For more common parts, like the plastics and metals and wiring inside each detonator, there are also questions about how the years spent in warheads might affect their integrity.

So workers at the nation’s nuclear labs and production sites spend a lot of time stressing and testing parts to make sure they’re safe. At the Energy Department’s Kansas City National Security Campus, where warheads are maintained and made, technicians put components through endless tests. They heat weapons parts to extreme temperatures, drop them at speeds simulating a plane crash, shoot them at high velocity out of testing guns and rattle and shake them for hours on end. The tests are meant to simulate real world scenarios — from hurtling toward a target to being carted in an Air Force truck over a long, rutty road.

Technicians at the Los Alamos National Lab conduct similar evaluations, putting plutonium under extreme stress, heat and pressure to ensure it is stable enough to blow up as intended. Just like the technicians in Kansas City, the ones in Los Alamos closely examine the tested parts and radioactive material to see if they caused any damage.

RELYING ON OLD BLUEPRINTS

The lack of explosive tests — banned since the George H.W. Bush administration by an international treaty — has also meant that the scientists have been forced to rely on warhead designs that were created many decades ago.

That’s because each of those original designs had been certified, and the best way to certify a weapon works as designed is to blow it up. Changing even one component introduces uncertainty.

Further complicating matters — because the weapons are so old — many of those original manufacturers and contractors have gone out of business. That has forced the nation’s nuclear labs to reverse engineer old parts, such as a peroxide that was used to treat warhead parts, but is no longer in production. So lab technicians are working to reinvent it.

Re-engineering parts is getting easier with advances in computer-aided design and 3D printing. Kansas City technicians are experimenting with 3D printers to create some warhead parts, such as a micro-honeycombed, rubbery layer that will serve as a cushion for a warhead radar systems.

THE WORKERS ARE YOUNGER THAN THE WARHEADS

It’s not unusual to see a 50-year-old warhead guarded or maintained by someone just out of high school, and ultimate custody of a nuclear weapon can fall on the shoulders of a service member who’s just 23.

That is what happened on a recent afternoon in Montana at Malmstrom Air Force Base, where Senior Airman Jacob Deas signed a paper assuming responsibility for an almost 3,000-pound Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile warhead, as it was lifted out of the Bravo-9 silo and escorted back to base for work.

A sea swell of government retirements has meant that experience level in the civilian nuclear workforce has shifted dramatically. At the Kansas City campus, for example, just about 6 percent of the workforce has been there 30 years or more — and over 60 percent has been at the facility for five years or less.

That change has meant more women have joined the workforce, too. In the cavernous hallways between Kansas City’s secured warhead workrooms are green and white nursing pods with a greeting: “Welcome mothers.”

At Los Alamos, workers’ uniform allowance now covers sports bras. Why? Because underwire bras were not compatible with the secured facilities’ many layers of metal detection and radiation monitoring.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

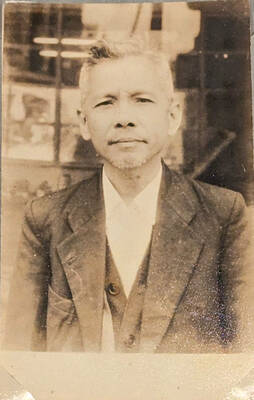

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only