July 17 to July 23

When Yeh Ken-chuang (葉根壯) came of age, the traditional skills of architecture and carpentry that had been in his family for four generations were disappearing. After helping his uncle Yeh Teh-ling (葉得令) construct ships, residences and temples for more than a decade, Yeh struck out on his own at the age of 28 in 1960 as a damusi (大木司, chief carpenter), earning his lifelong title “Chief Chuang” (壯司).

Around this time, builders in his homeland of Penghu were increasingly using reinforced concrete instead of wood, due to the humid climate. The period also saw a frenzy in temple construction as the economy improved, meaning there was plenty of work for Yeh.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Adept in non-structural techniques such as doors, windows and furniture, as well as the intricate carvings and detailed decorations that adorned the structures, Yeh was able to adapt his skills, leading the reconstruction of the historic Hsiliao Daitian Temple (西寮代天宮) on Penghu’s main island in 1963.

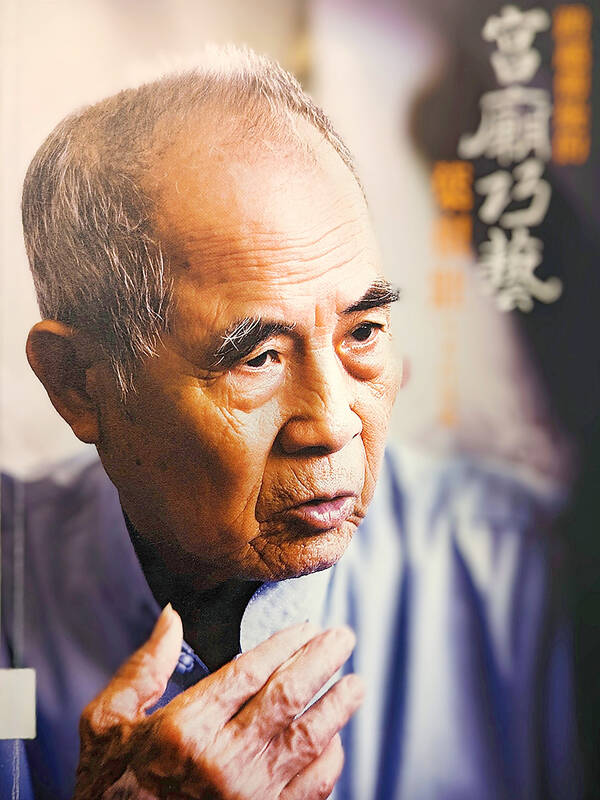

According to the book Crossing Traditions in Yeh Ken-chuang’s Large-scale Carpentry Skills (宮廟巧藝 :跨越傳統的葉根壯大木作技術), it was Penghu’s first temple that used a purely reinforced concrete structure.

Before his life was cut short, Yeh created more than 70 temples and related structures across the various islands of Penghu and left behind more than 230 building plans.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Although Yeh could have built temples and other structures on Taiwan proper, he only worked on a handful of projects outside of Penghu because he wanted to be close to his family.

CLAN OF CARPENTERS

The Yeh family’s woodworking tradition began with Yeh Ma-li (葉媽利), who learned the architecture and carpentry trade from an unknown master on Kinmen. The Yehs trace their roots to Kinmen, although this branch had been living in Penghu since the early 1600s.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yeh Ma-li was Penghu’s chief temple builder between 1860 and 1890. His daughter-in-law once said that at the height of his prolific career, only three temples on Penghu were not constructed by him. Besides his sons, Yeh Ma-li also took in a young neighbor Hsieh Chiang (謝江), whose later work includes the Guanyin Temple (觀音亭) and City God Temple (城隍廟) in Penghu’s largest town of Magong (馬公). Hsieh’s descendants also became prominent temple builders.

Yeh Ma-li’s grandson Yeh Te-ling became Hsieh’s apprentice since his father died when he was young. Yeh Te-ling was also versed in both large-scale and small-scale carpentry, but unfortunately few temples he built remain.

Yeh Ken-chuang was born in 1932 to Yeh Te-ling’s older brother Yeh Tung (葉東), who was also a carpenter. Yeh Tung, who focused mostly on residences, probably learned from his father Yeh Yuan (葉元), who died before his sons finished their apprenticeships. Only Yeh Te-ling received a complete training under Hsieh.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yeh Ken-chuang’s formal education was cut short by World War II, so he began working at his brother-in-law’s grocery store at the age of 13. The store’s landlord taught him math and weighing skills as well as how to calculate the amount of materials needed for a job, greatly helping him in his career as a builder.

The brother-in-law died when Yeh Ken-chuang was 17 years old, so the teenager asked Yeh Te-ling if he could help him build Wufu Temple (吳府宮) on Wangan Island (望安). Yeh Ken-chuang would become one of his uncle’s five official disciples, training with him for 11 years and carrying on the family name.

ADAPTING TO THE NEW

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

During the first years under his uncle, most of their projects were residences and ships. Only later was there a need for temple work suddenly surge. Yeh’s uncle was often gone for weeks overseeing construction across the archipelago, and Yeh was often thrust into the spotlight on projects closer to home. The first temple he completed on his own was the Hsu Village Gangyuan Temple (許家村港元寺), which has been since demolished and rebuilt.

Wood structures in Penghu were susceptible to decay, especially as the strong monsoon winds contained sea salt. Once reinforced concrete became readily available, building methods began shifting immediately.

Yeh employed the new reinforced concrete building methods, and in just his third year in business, he built the Hsiliao Daitian Temple. It was a daring attempt for him, replacing the major supports with concrete and simplifying the complicated wood layering techniques. Yeh still maintained his passion for wood structures, building in that same year the Lungmen Guanyin Temple (龍門觀音寺). He mostly used a combination of timber and reinforced concrete until the mid-1970s, after which he completely switched to reinforced concrete.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Despite the shift, Yeh was able to maintain the proportions, designs and other essential elements of a traditional temple, and use modern materials to create decorations that resembled the old. At the same time, he continued to refine and evolve his knowledge of reinforced concrete construction.

He was enthusiastic about preservation and passing on this traditional knowledge. In 2008, he became an instructor with a Penghu traditional architecture program and was also involved in other ventures.

In 2010, Yeh was nominated by the government as a preserver of large-scale carpentry skills, with the description reading: “He’s adept in adapting his traditional skills to any size, style and construction method. Despite being impacted by the shift in building material, he still adheres to the traditional system required in large-scale carpentry.”

The final evaluation was set for July 29, 2014, and if he passed Yeh would have officially become a “national living treasure” (人間國寶). However, just six days before that day, TransAsia Airways Flight 222 from Kaohsiung crashed near Magong Airport’s runway, killing 47 people. Yeh and his wife were among the victims. He was 82 years old.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall