May 8 to May 14

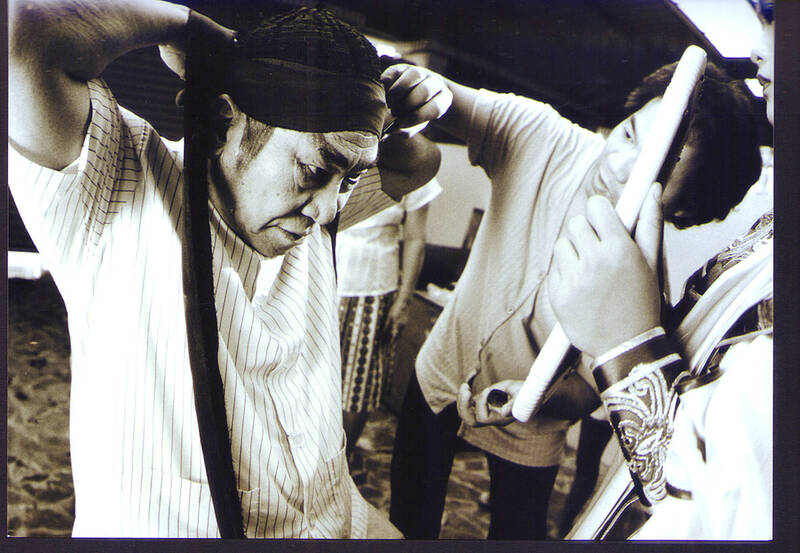

In the old days, traditional theater performers were often “sold” as children to troupes by destitute parents — but a 13-year-old Chen Ming-chi (陳明吉) ran away from home to join the opera.

Having quit school after the third grade to support his family, one of his tasks was to sell sweet refreshments to the audience during Taiwanese opera (gezaixi, 歌仔戲) performances in front of the local temple. He was mesmerized, Chiu Ting (邱婷) writes in the book, Ming Hwa Yuan : A Taiwanese Opera Family (明華園:台灣戲曲世家), and one day he lingered long after the show ended.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A dan performer spotted Chen and started chatting with him. He told the youngster he could make just as much money playing bit roles in their troupe, and if he became a major player he’d earn even more.

After finding out that the performers, who had been in town for a month, were leaving the following day, Chen decided that he would run away with them. He hid all day and ignored the calls of his family looking for him, and made a run for the troupe’s truck as soon as their final performance ended. He saw his stepfather waiting for him by the vehicle, so he told the actors to meet him by the fields instead. The plan worked, and there was no turning back.

Five years later, in 1929, Chen launched his own troupe, Ming Hwa (明華), which, after many ups and downs, became Ming Hwa Yuan Arts & Cultural Group (明華園戲劇總團), which remains one of the most prestigious opera companies in the nation today.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan National University of the Arts

Chen died in 1997, but under management of his son Chen Sheng-fu (陳勝福), the troupe modernized into a successful performing arts empire with nine independent companies, touring Taiwan and the world and keeping this traditional art relevant.

OPERATIC ORIGINS

According to “The Study of Ming Hwa Yuan Taiwanese Opera Group in Development Process and Event Management” (明華園之組織發展與展演活動管理研究) by Chou Ying-fen (周瑛芬), most traditional Han performing arts were brought by immigrants from China to Taiwan, where they took on unique local characteristics.

Photo courtesy of Ministry of Culture

Gezaixi, although influenced by the various Chinese opera styles, is considered one of the few Han artforms that developed locally, emerging in the late 19th century. Early practitioners often improvised in town plazas and put on shows during temple festivals.

The content was easy to understand for common folk, and as Taiwan urbanized under Japanese rule beginning in 1895, these troupes were often hired to perform indoors at business events. Taiwanese opera soared in popularity in just two decades — by 1928, it had become the preferred theatrical style over Beijing, Baizi and other Chinese styles.

Intellectuals criticized Taiwanese opera as vulgar and promoting bad morals, but they couldn’t stop the tide. Japanese imperialization put a halt to the shows, however, as they banned everything Taiwanese and Chinese under their kominka assimilation policy in the late 1930s.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In 1942, the Japanese launched the Taiwan Theater Association, which assumed control of all troupes in Taiwan. Committee members closely inspected the performance content of each show, and only those approved could take the stage. However, many troupes performed the beloved traditional material in secret, and only when police arrived would they hurriedly put on Japanese clothes and start singing patriotic lyrics.

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) allowed the art form to flourish again after their arrival in 1945, and in a few years after hundreds of Taiwanese opera groups had appeared. The Taiwan Provincial Local Theater Association (臺灣省地方戲劇協進會) boasted more than 300 opera companies when it was established in 1952.

RISING TO THE TOP

Chen Ming-chi was born to an unmarried mother in Pingtung County’s Checheng Township (車城) in 1912, which was a great dishonor to her entire family in those days. She was hastily married to a poor laborer, and they could only support Chen’s education until the third grade, after which he dropped out and began doing odd jobs.

After running away from home, Chen’s first few weeks in the Xincaiyun (新彩雲) troupe involved only running errands for the performers for small change. One laosheng actor told Chen that this troupe didn’t have much of a future, and the two jumped ship to another company called Hesheng (和聲).

The laosheng begged Hesheng’s leader to give Chen a chance, and Chen took the stage for the first time in their following show.

Chen only had one line, but the boss saw much potential from his looks, poise and charisma. He was officially hired that night.

About a year later, the troupe performed in his hometown. A resident recognized Chen and told his mother, who rushed to the stage. During the tearful reunion, Chen’s colleagues assured his mother of his talent, and told her it was a good job for someone his age. Chen gave his mother some of his savings, telling her that he was going to be fine.

A few years later, the leader of Hesheng unexpectedly died. After pondering going their own ways, Chen and his colleagues decided to take over the troupe. After absorbing members of another disbanded group, they formed Jinhexing (金和興), and even though Chen was the youngest at the age of 17, he was elected troupe leader.

HARD TIMES

Jinhexing did not last long, as the Japanese authorities forced it to disband. The following year, Chen started the Mingsheng Opera Troupe (明聲) and signed a contract with theater owner Tsai Ping-hua (蔡炳華). Tsai wanted to include his name in the group’s title, so it was changed to Ming Hwa. It was immensely popular for the next decade, known for its tight plots, complex compositions and creative use of scenery and backdrops.

In 1942, Ming Hwa was forced to change its name to the Ming Hwa Drama Troupe and could only put on government-approved shows in the Japanese language. The content was still derived from traditional Taiwanese stories and dialogue, but the ancient Chinese characters were changed to suit modern Japanese roles. The performers wore Japanese clothing and the musicians played Western classical tunes.

The KMT takeover revitalized the opera scene. Chen added “yuan” (garden, compound) to the troupe’s name, hoping that it could become a flourishing big family. On Oct. 27, 1945, just two days after the Japanese surrender in Taiwan, the troupe was invited to Tainan’s Longguan Theater (龍館戲院) where they put on 52 straight sold out shows.

The next 10 years were fruitful, but the troupe also had to compete with other forms of entertainment from China and the West. The advent of television in the 1960s struck a major blow, as all three national channels broadcast Taiwanese opera performances, causing live attendance to drop sharply.

Chen was forced to sell his troupe headquarters and beloved stage backdrops, and finally in 1964 he sold the troupe to a businessman. He spent a year saving money to buy the troupe back, but things did not get easier, as they were limited to outdoor shows at festivals and temple ceremonies.

Chen Ming-chi eventually handed leadership of the troupe to Chen Sheng-fu, the only family member who was not a performer. Chen Sheng-fu aimed to turn Taiwanese opera into a proper, respected cultural artform, and aided by a renewed interest in traditional culture among intellectuals during the late 1970s and 1980s, he succeeded in completely turning things around.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

We have reached the point where, on any given day, it has become shocking if nothing shocking is happening in the news. This is especially true of Taiwan, which is in the crosshairs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), uniquely vulnerable to events happening in the US and Japan and where domestic politics has turned toxic and self-destructive. There are big forces at play far beyond our ability to control them. Feelings of helplessness are no joke and can lead to serious health issues. It should come as no surprise that a Strategic Market Research report is predicting a Compound