April 10 to April 16

Liu Hsing-chin (劉興欽) first began drawing comics to stop children from reading comics.

Around 1954, palm-sized comic books about sorcery and martial arts were all the craze in Taipei’s elementary schools. However, things got out of hand as some children began believing the content, running away into the mountains to find an immortal master. Some never made it home alive.

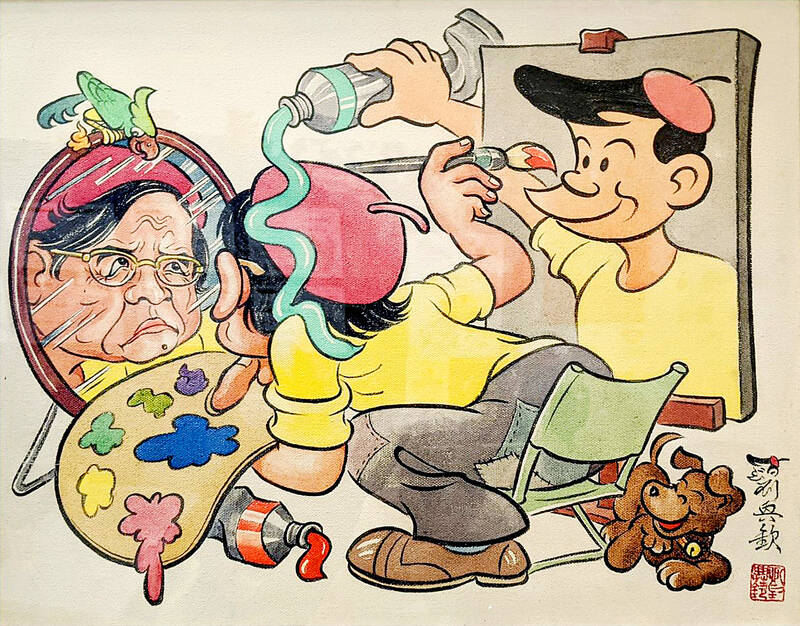

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Liu was a teacher at Yongle Elementary School, and the principal asked him if he had any suggestions.

“Let’s fight poison with poison,” Liu said, and created his first 16-page comic book. It unexpectedly sold well, earning him five times his monthly salary. Before this, he was subsisting on bread and water as most of his pay went to his sick father’s medical expenses.

Liu’s initial success didn’t pay off, however, as a friend who offered to help him sell his comics ran off with the money. Liu wasn’t discouraged, and instead tried to get regularly featured in one of the nation’s newspapers or magazines. He was rejected at first, but his artwork improved during the process. Finally, he made it into several children’s publications, including the state-run Elementary Schooler’s Pictorial (小學生畫刊), which allowed his character Xiaoqing (小青) to be seen in all elementary schools across the nation.

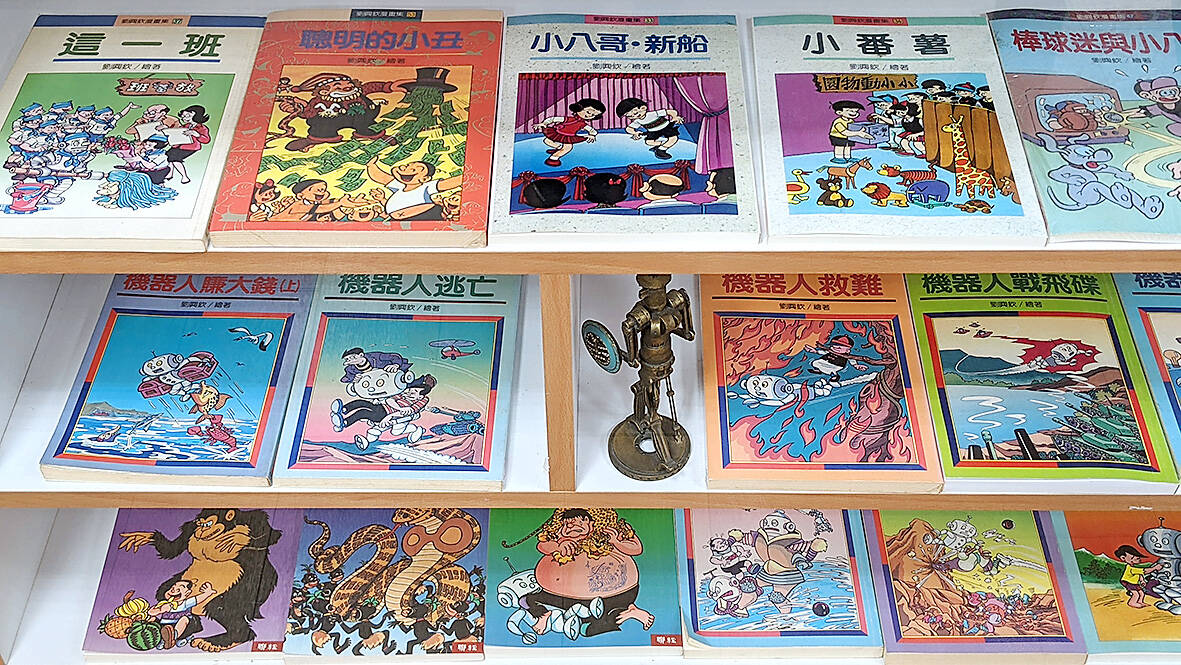

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Over the decades, Liu became one of the nation’s most popular comic artists, with his signature characters Big Auntie, Brother A-san and Robot. Known for his quick wit since he was a child in Hsinchu County’s Neiwan Township (內灣), Liu was also a prolific inventor, holding more than 100 patents in Taiwan and abroad. A comic museum is dedicated to him on Neiwan Old Street.

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Liu was born in 1934 in Dabeishan (大背山), an impoverished village in the rugged hills of Neipu. His father was a rice and tea farmer who also rented a coal mine.

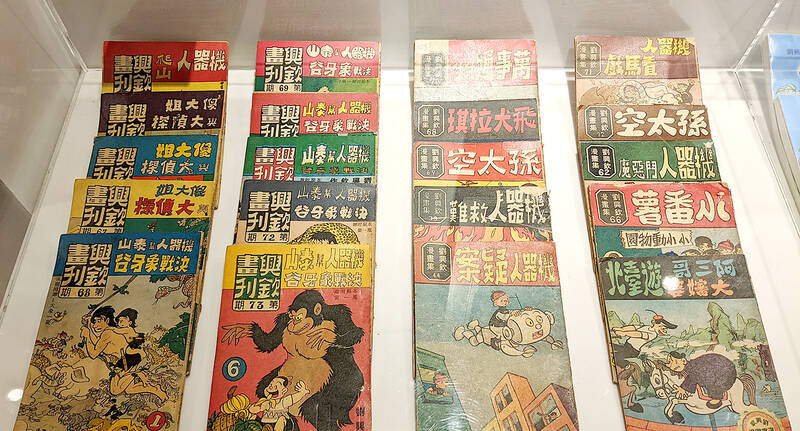

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Most families were illiterate and kept their children from going to school so they could help at home. The school’s principal and his wife offered to help students watch their cows and younger siblings to encourage attendance.

“Nobody told me how to motivate myself, and nobody discovered my artistic talent,” Liu writes in his autobiography, The Man Who Ate Ideas (吃點子的人).

His one apparent talent, however, was sucking the excess breast milk from the female tea workers on the family farm. It was common practice for young children to do so, as the women were away from their infants and felt pain and discomfort in their chests while working. He also gobbled up discarded fruit from neighboring orchards and foraged for insects, crabs, wild plants, berries and honey — becoming an exceptionally strong child who rarely got sick. The enterprising Liu also gathered medicinal herbs and asked the school principal to sell them in town in exchange for school supplies.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“I never shirked when facing problems, and I always tried to find a solution,” he writes.

Clever and resourceful, older relatives liked to bring him along on outings, as he often helped them avoid swindlers.

“I always found ways to complete my chores earlier so I had extra time to play,” Liu writes. “And whenever disputes arose in the village, I would think of a creative way to resolve them.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Liu’s father instilled in him the importance of having good morals and a clear conscience, which affected his future comics.

“I decided that my art had to be socially responsible, and I steered clear of sex and violence so that both adults and children could enjoy my works,” he writes.

ARTISTIC SUCCESS

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Liu didn’t have big dreams as a child, he just wanted to be admitted to junior high school so that he could wear shoes for the first time since that was a requirement for admission. In junior high, he wanted to attend a high school that provided meals and lodging since his family couldn’t afford it.

“I took everything step by step, so I was very happy every day,” he writes.

Liu eventually graduated from teacher’s college and found work in Taipei. He painted one watercolor per day and tried to sell it at his friend’s bookstore, but none of them ever sold.

At that time, most comic artists were Mainlanders, as Taiwanese were still learning Mandarin and also didn’t have the background to create art that suited the government’s agenda. Soon after his comics were first published, Liu participated in the 1955 Anti-Communist Art Exhibition, creating two strips that sardonically depicted how harsh life was in China under the Mao Zedong (毛澤東).

Many of his peers refused to believe that there was such a talented Taiwanese artist and accused him of plagiarism, but influential artist Liang Chung-ming (梁中銘) defended him and even introduced him at a banquet held by the Central Daily News (中央日報). Liu became a frequent guest at Liang’s house, often asking him for tips in drawing.

When Liu’s creativity stagnated, his friends suggested that he do something exciting such as going to a nightclub. But he persevered, drawing on his own experiences for inspiration.

Big Auntie is based on his mother, who he described as a “humorous person who could fall from the second floor and not get hurt; she’s adept at singing mountain songs and even won first place in a contest; and even in her old age, she could climb stairs faster than me.”

Nicknamed “Thunder God Mom,” she had a loud booming voice and, possessing immense strength, she took part in all sorts of hard labor on the farm in addition to birthing 10 children. She had a strong sense of justice and didn’t hesitate to protect those in trouble or scold people who didn’t work hard or engaged in questionable activities, regardless of their status.

She was also generous and always willing to volunteer her time and energy for others.

Big Auntie was a smash success, and the publisher asked Liu to create more rural characters — this time, he transformed himself into Brother A-san.

CHANGING GEARS

In those Martial Law days, comic artists had to be very careful not to incur the wrath of the government. One time, Liu drew a strip about a rich old man and his spoiled hooligan son, and gave the old man a rare surname. It just happened that there was a high ranking official with the surname and a son around the same age, and they reported this to president Chiang kai-shek (蔣介石).

Liu was cleared after a brief investigation, although he continued to be harassed by the authorities for a period of time. Others weren’t as fortunate. One classmate was jailed for six months for a single dialogue bubble.

When Taiwanese comics went into decline in the late 1960s, Liu shifted his focus to inventing. He had done poorly in maths and science, but with the 1968 creation of a character named Robot, he began adding scientific elements to his work. On a dare from a young reader, he created a “learning robot” that displayed flash cards and clapped its hands when the user got the answer right. The robot became a hit with children and parents around the world and sold well for over three decades.

Liu obtained 138 patents in seven years and won several invention awards, but he says only two or three of them were actually produced. Investors poured money into his auto-sharpening pencil, but by the time it was finally developed, there were already similar products on the market.

Again, people refused to believe that a comic artist could invent so many things and accused him of bribing the government.

To these critics he said: “As long as you can draw and you have creativity, inventing is really not that hard.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how