Feb 27 to Mar 5

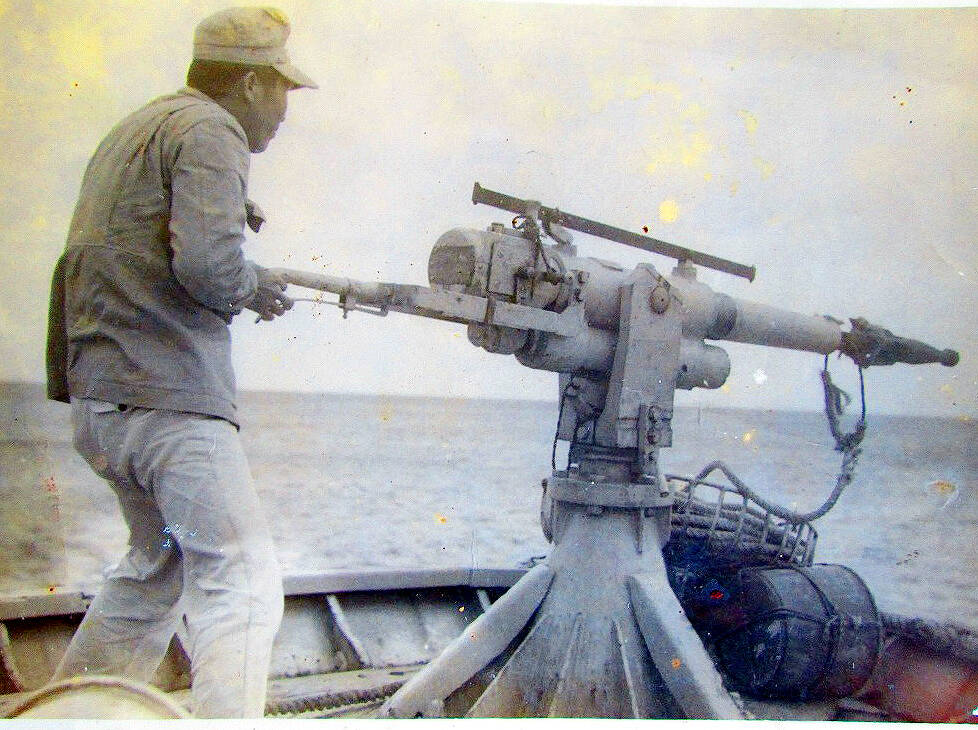

Tsai Wen-chin (蔡文進) waited and waited for the right moment to fire the harpoon cannon. He tells Yang Chen-yuan (楊政源) in the 2013 book, Sea Blue Blood (海藍色的血液) that the distance between the ship and the whale was twice as far as what he had practiced.

With the Japanese chief harpoonist urging him on and the entire crew getting restless, Tsai fired his first shot. It was a success. On that trip in the mid-1950s, Tsai hit the marks on both shots he fired, while the chief harpoonist got eight out of 10.

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsien, Taipei Times

“That’s 80 percent vs 100 percent,” he said proudly nearly 60 years later, after whaling had long been banned.

In July 1981, Tsai’s 25-year career came to an end when, facing international pressure, the government outlawed the practice and revoked all whaling licenses. Launched by the Japanese in 1913 and restarted in 1955, it was a lucrative industry in the Hengchun Peninsula (恆春) — the torii gate in front of the Eluanbi Shinto Shrine was even made of whale ribs.

For the past 15 years, local researchers led by Nien Chi-cheng (念吉成) have been interviewing the aging whalers and collecting historic material to piece together this often-forgotten past. On Monday, the Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister paper) reported that Nien will soon be holding an exhibition with never-seen material in Hengchun.

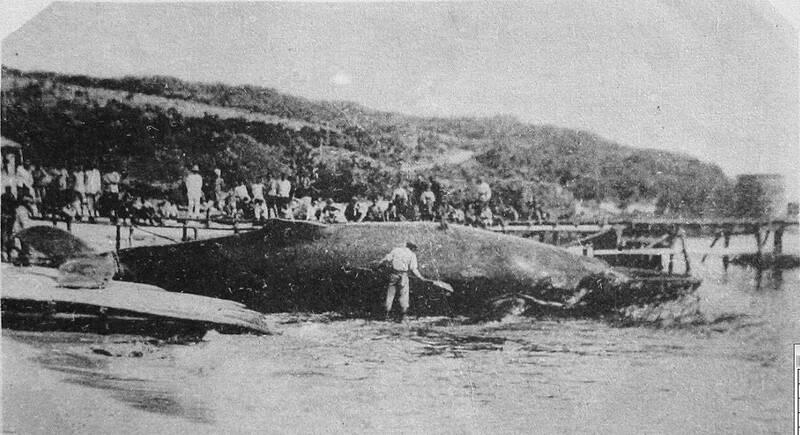

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repositories

“The Hengchun peninsula was once a thriving habitat for whales, but today there are only occasional surprise sightings,” Nien says. “This exhibition is also to reflect on human greed, and to preserve this past of Hengchun.”

A NEW INDUSTRY

Qing-era documents regarding whales in Taiwan indicate that residents would use their meat and blubber whenever they washed ashore, whether dead or alive. Commercial whale hunting did not begin until 1913, when a Japanese company set up operations in today’s Nanwan (南灣) in Kenting National Park.

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsien, Taipei Times

Using smaller boats and lacking processing equipment, and this venture fizzled out after two years. According to a 1994 Fisheries Extension article by Hu Hsing-hua (胡興華), in 1920 the governor-general’s office commisioned a Japanese whaling company to restart operations in Nanwan.

They managed to kill 34 whales that year, proving that the industry was feasible, and the government then imported two whaling ships fitted with harpoon cannons from Norway and hired Norwegian experts to operate them. The processed meat and oil were sent back to Japan. They were rarely consumed by locals.

To prevent overhunting, the government only allowed two ships to operate at a time between December and March on the waters between Hengchun and Taitung. The three main species hunted were humpback whales, sperm whales and fin whales. The most bountiful year was 1929, with 62 animals hauled ashore.

Operations were suspended in 1943 due to World War II. In 1953, Hsiang Teh Fishery Company (祥德漁業) began discussions with a Japanese counterpart to revive Taiwan’s whaling industry, and after four years of discussion, they began operations in Banana Bay (香蕉灣) further to the southeast. The Japanese provided the ships and personnel, while the Taiwanese built the processing facilities and port. They split the profits 60-40.

The first voyage lasted over a month, returning home with four humpback whales. Tsai was one of the company’s first Taiwanese crewmembers, joining as a harpooning assistant. As before, almost all of the bounty was exported overseas.

“The meat is not suitable for Taiwanese tastes,” Tsai replies when Yang asks if Hengchun residents consumed whale meat. He was given a few cans by the company to try — “It really tastes terrible!”

UNSATISFACTORY YIELDS

Due to unsatisfactory yields, the Japanese company pulled out in 1960. Hsiang Teh then joined forces with the Provincial Fisheries Agency, who retrofitted the patrol boat “Huyu No. 1” (護漁一號) as the first Taiwanese-made whaling vessel.

This partnership ended three years later again due to lack of productivity, and Hsiang Teh then purchased a Japanese ship to do it on their own. They soon gave up.

Huang attributes the failure to lack of technical experts as well as unstable supply. Under the agreement, five Taiwanese staff were allowed on the ship, but they were only able to provide three due to a shortage of trained whalers. And unlike Japan, where its whaling ships could move around the country according to migration patterns, Taiwan’s ships and processing facilities often sat idle for much of the year.

The allure remained, however, and in 1976, Ming Tai Aquatic Products (銘泰水產) obtained the 600-ton Sea Bird (海雁號) and set out in April with a crew of 26. During eight journeys in two years, it caught about 290 whales, and their success spurred other companies to vie for a piece of the pie.

While Taiwan was not part of the International Whaling Commission (IWC), the government still limited the licenses it issued and drafted laws to regulate the industry according to international standards. Only three more licenses were handed out by 1979.

END OF THE LINE

In 1978, the IWC began tightening restrictions on whaling, and also applied pressure on Taiwan. William A. Brown, director of the newly established American Institute in Taiwan’s Taipei office, wrote to the government a year later, noting that the US was concerned about Taiwan’s expansion of its whaling industry at a time when others were contracting theirs. He sternly warned that noncompliance could lead to the US boycotting Taiwanese aquatic products.

The government responded that they would not encourage further development, but maintained that their limited activity would not affect the whale population much. The Americans continued to pressure Taiwan over the year, accusing them of “smuggling” whale meat into Japan as products of South Korea and even trying to block the nation’s exports to Japan through the IWC.

What’s ironic is that due to Taiwan’s international status, it could not join the IWC, and was not allowed to attend the organization’s 1980 conference in London, even as an observer. But later that year, the government released a detailed report of its whaling activity and decided to completely ban the industry.

In 1990, the Earth Trust organization recorded a video of a bloody dolphin hunting drive in Penghu and screened it in the US, leading to massive international outcry. Taiwan had just enacted its Wildlife Conservation Act (野生動物保育法) a year earlier, and this event led to all whales and dolphins being placed on the protected list.

With whaling banned, Hu suggested the rise of a new industry — whale watching.

In July 1997, the Haijing (海鯨號) vessel embarked on the nation’s first whale tourism voyage from Hualien. The ship survived a fire last year and is still in operation.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson

Another moment of the US making permanent concessions for transient gains, which appears to be longstanding US policy with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), occurred last week when President Donald Trump announced that weapons sales to Taiwan would be delayed in order to arrange a meeting with the PRC dictator Xi Jinping (習近平). There were “concerns among some in the Trump administration that greenlighting the weapons deal would derail Trump’s coming visit to Beijing, according to US officials,” the Wall Street Journal reported. It attributed the suspension of the weapons sale to pressure from Xi. While some might shrug