The discovery of dozens of beakers and bowls in a mummification workshop has helped reveal how ancient Egyptians embalmed their dead, with some “surprising” ingredients imported from as far as Southeast Asia, a study said Wednesday.

The exceptional collection of pottery, dating from around 664-525BC, was found at the bottom of a 13-meter well at the Saqqara Necropolis south of Cairo in 2016.

Inside the vessels, researchers detected tree resin from Asia, cedar oil from Lebanon and bitumen from the Dead Sea, showing that global trade helped embalmers source the very best ingredients from across the world.

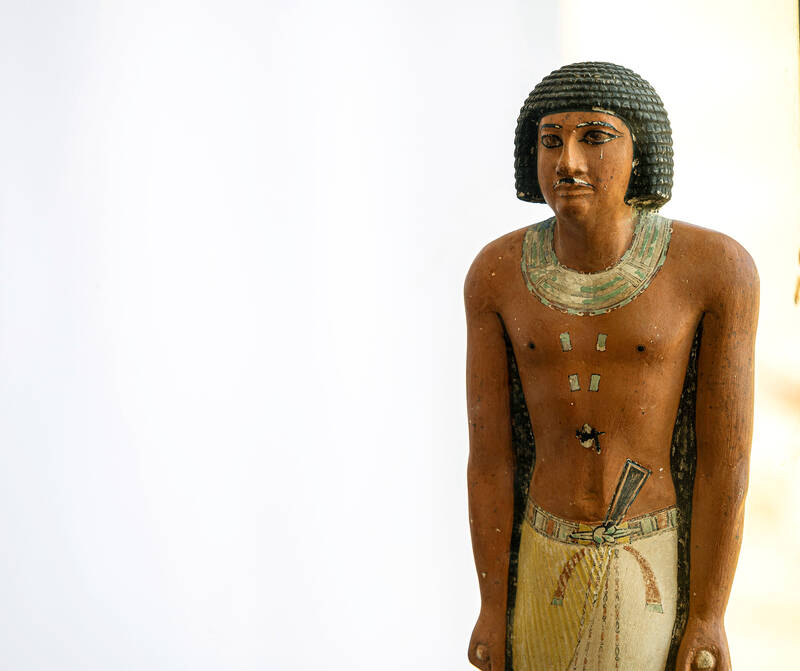

Photo: AFP

Ancient Egyptians developed a remarkably advanced process to embalm corpses, believing that if bodies were kept intact they would reach the afterlife.

The process took up to 70 days. It involved desiccating the body with natron salt, and evisceration — removing the lungs, stomach, intestines and liver. The brain also came out.

Then the embalmers, accompanied by priests, washed the body and used a variety of substances to prevent it from decomposing.

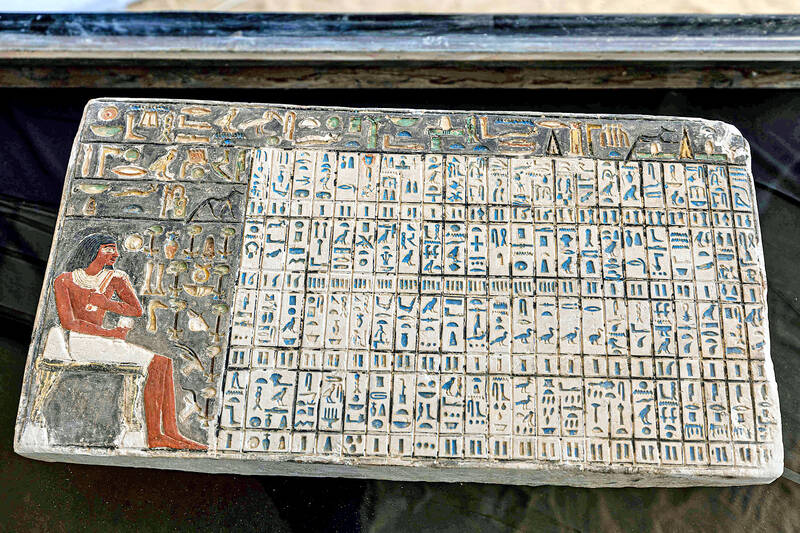

Photo: AFP

But exactly how this was done has largely remained lost to time.

Now a team of researchers from Germany’s Tuebingen and Munich universities in collaboration with the National Research Center in Cairo has found some answers by analyzing the residue in 31 ceramic vessels found at the Saqqara mummification workshop.

By comparing the residue to containers found in adjacent tombs, they were able to identify which chemicals were used.

‘TO MAKE THIS ODOR PLEASANT’

The substances had “antifungal, anti-bacterial properties” which helped “preserve human tissues and reduce unpleasant smells,” the study’s lead author, Maxime Rageot, told a press conference.

Helpfully, the vessels have labels on them. “To wash,” reads the label of one bowl, while another says: “to make his odor pleasant.”

The head received the most care with three different concoctions — one of which was labeled “to put on his head.”

“We have known the names of many of these embalming ingredients since ancient Egyptian writings were deciphered,” Egyptologist Susanne Beck said in a statement from Tuebingen University.

“But until now, we could only guess at what substances were behind each name.”

The labels also helped Egyptologists clear up some confusion about the names of some of the substances.

The scant details we have about the mummification process mostly comes from ancient papyrus, with Greek authors such as Herodotus often filling in gaps.

By identifying the residue in their new bowls, the researchers found that the word antiu, which has long been translated as myrrh or frankincense, can actually be a mixture of numerous different ingredients. In Saqqara, the bowl labeled antiu was a blend of cedar oil, juniper or cypress oil and animal fats.

EMBALMING DROVE ‘GLOBALIZATION’

The discovery showed the ancient Egyptians had built up “enormous knowledge accumulated through centuries of embalming,” said Philipp Stockhammer of Germany’s Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology.

For example, they knew that if the body was taken out of the natron salt, then it was in danger of being immediately “colonized by microbes that would eat up the skin,” he said.

Stockhammer said “one of the most surprising findings” was the presence of resins, such as dammar and elemi, which likely came from tropical forests in Southeast Asia, as well as signs of Pistacia, juniper, cypress and olive trees from the Mediterranean.

The diversity of substances “shows us that the industry of embalming” drove momentum for “globalization,” Stockhammer said.

It also shows that “Egyptian embalmers were very interested to experiment and get access to other resins and tars with interesting properties,” he added.

The embalmers are believed to have taken advantage of a trade route that came to Egypt through present-day Indonesia, India, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea from around 2000 BC.

The Saqqara excavation was led by Ramadan Hussein, a Tuebingen University archaeologist, who died last year before the research was published in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

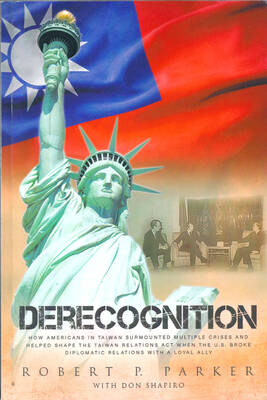

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any