A painting by Edvard Munch that lay hidden in a barn alongside a version of The Scream, to keep it out of the hands of German soldiers, is to be sold at auction and the proceeds split with the family of the Jewish man who was forced to sell it when fleeing the Nazis.

The monumental Dance on the Beach will be auctioned by Sotheby’s in London on 1 March and is estimated to fetch around £12 million to £20 million (US$14.7 million to US$24.5 million).

Just over four meters wide, it is an enigmatic composition featuring dancing figures and two of the artist’s greatest loves — relationships that ended in tragedy and heartbreak.

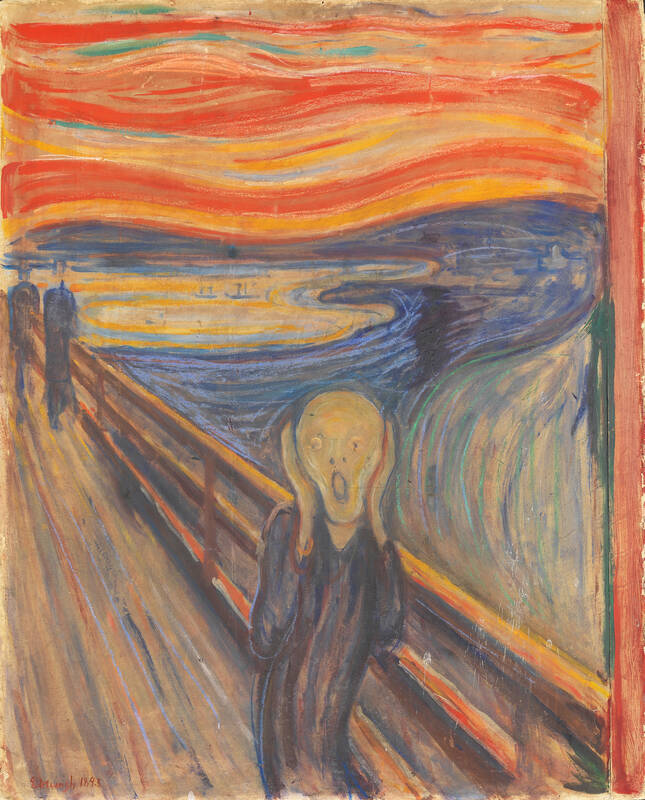

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It is being sold by the family of Thomas Olsen, a Norwegian shipowner and Munch’s neighbor, who died in 1969. He had bought it in Oslo in 1934, just months after Curt Glaser, an eminent German academic, had been forced to sell it in Berlin.

Both men had been close friends of the artist, who had painted portraits of their respective wives, Henriette Olsen and Elsa Glaser.

Now, through Sotheby’s, their descendants have negotiated its forthcoming sale, putting right at least one wrong of the Nazis who, in the 1930s, included Munch among artists banned as “degenerate.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Dance on the Beach was part of a masterpiece of 12 major panels, which Max Reinhardt, the theater director, commissioned in 1906 for his avant-garde theater in Berlin. Munch designed sets for his stagings of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts and Hedda Gabler and, in creating his theater in the round, Reinhardt asked him to paint a frieze that would surround the audience in a hall on the upper level, immersing them in what the artist called “images from the modern psyche.”

When the theater was refurbished in 1912, the frieze was split up and Dance on the Beach was acquired by Glaser, director of the Berlin State Art Library, who published the first German monograph on Munch, among other scholarly publications, and assembled an outstanding art collection. Persecuted by the Nazis for his Jewish background, Glaser lost his job and his apartment was seized. He sold his collection and escaped to Switzerland, eventually making his way to America, where he died in 1943.

Olsen hung Dance on the Beach in the first-class lounge of his passenger liner, the MS Black Watch, which traveled between Oslo and Newcastle over several months in 1939. It was part of his extraordinary collection of about 30 works by Munch. After Britain declared war on Germany, he hid them in a remote barn in the Norwegian forest. They included a version of The Scream, which Sotheby’s sold on behalf of the Olsen family for a record US$119.9 million in 2012. Its proceeds funded Petter Olsen’s museum at Ramme, on the Oslo Fjord, and the restoration of Munch’s house there.

Lucian Simmons, Sotheby’s vice-chairman and worldwide head of restitution, told the Observer: “This isn’t just an amazing painting, which has this incredible history of being commissioned by Max Reinhardt, who was a superstar in the theater world, but it also has this incredible twin history of belonging to these two great patrons of this artist.”

He added: “Glaser and his first wife regularly visited Munch in Oslo and, when Munch visited Berlin in the 1920s, he stayed with the Glasers. So it wasn’t just a pure patronage relationship. Likewise, the Olsens had a house right next door to Munch’s house. This is a phenomenal picture — and it has a phenomenal history.”

The figures in Dance on the Beach are thought to represent innocence, love, life and death, recurring themes for Munch, who faced more than his fair share of tragedy. He lost his mother when he was five and his older sister, nine years later — both to tuberculosis — while his elder sister spent much of her life in a mental hospital. Munch was to suffer an acute breakdown in 1908.

Simon Shaw, vice-chairman of Sotheby’s New York, said: “Alongside immediately recognizable images such as the scream, the vampire, Madonna and girls on the bridge, depictions of figures dancing became a key motif in the artist’s works from the late 1890s onwards.”

Dance on the Beach captures that sense of “life playing out before his [Munch’s] eyes,” he said, incorporating many of the most important motifs of his oeuvre, as well as the people that plagued the artist’s memory.

In the foreground, two of Munch’s greatest loves haunt the canvas — Tulla Larsen and Millie Thaulow.

“The former was a turbulent affair that would end in Munch shooting his own hand in the heat of passion, and the latter was his cousin’s wife, and Munch’s first love,” Shaw said.

Dance on the Beach is likely to spark worldwide interest as it is the only part of the frieze cycle that remains in private hands. All the others are in museums. It will go on public view before the auction at Sotheby’s in London, from Feb. 22 to March 1.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any