Nov. 21 to Nov. 27

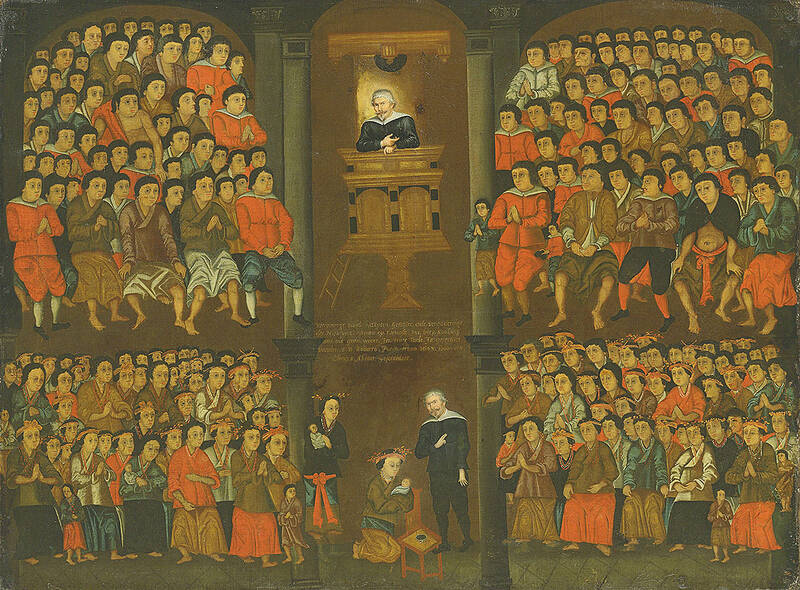

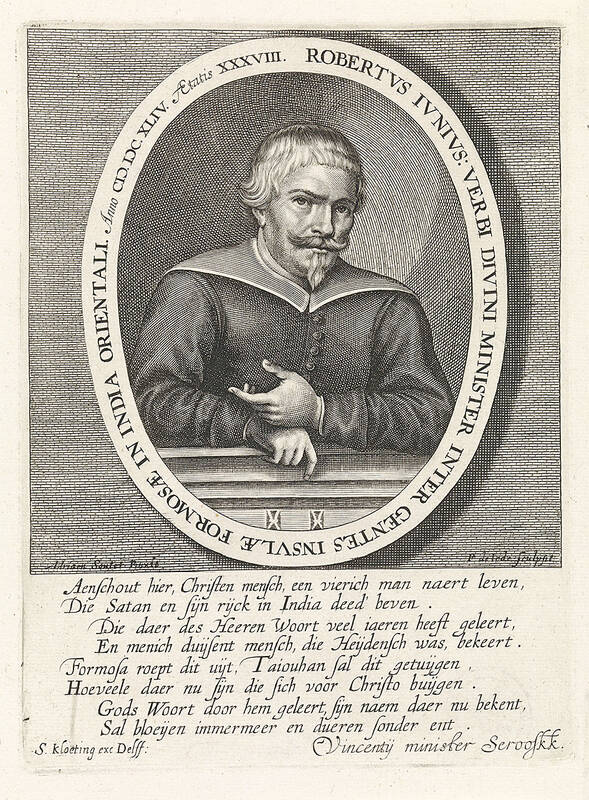

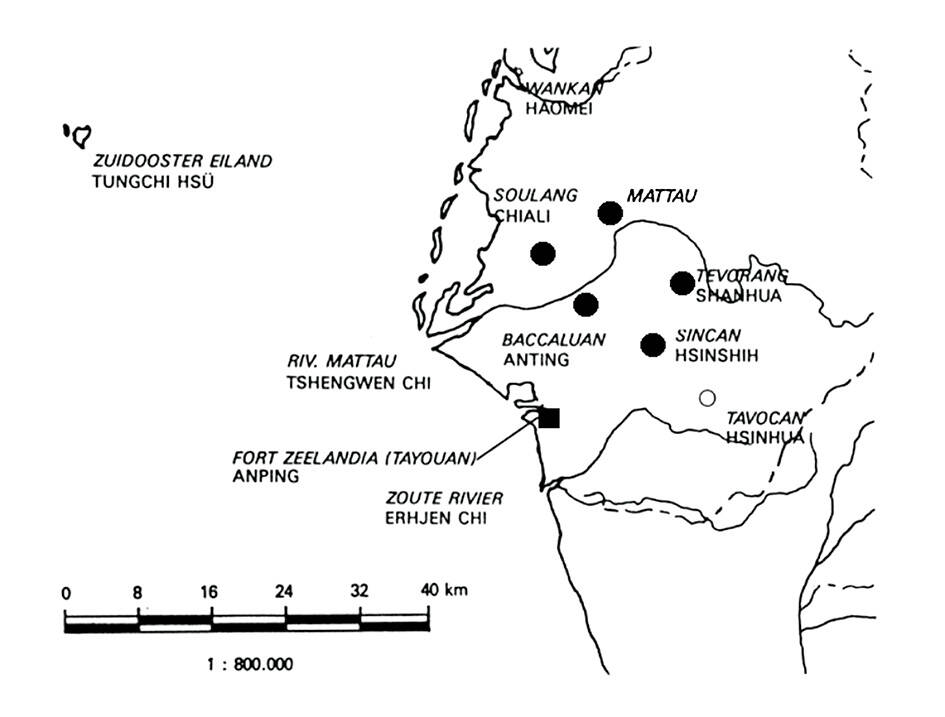

Dutch missionary Robert Junius waited six years for reinforcements to arrive. Once they did, he set out with them from Fort Provintia (today’s Tainan) in the morning of Nov. 23, 1635, soon linking up with their long-time indigenous allies from the village of Sincan (present-day Sinshih District, 新市).

Their target was Mattau (today’s Madou District, 麻豆), the largest and most powerful Siraya settlement in the area. They had been disrupting Dutch operations as early as 1623, and in a 1629 ambush killed 60 soldiers before raiding their sworn enemies at Sincan. The Dutch did not have the enough men to exact revenge, and Junius writes in a report to Dutch East India Company (VOC) headquarters that as long as Mattau was not “chastised,” the surrounding people would never take their authority seriously.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Even Sincan, which was the first village to ally themselves with the Dutch, planned on a mass uprising in September of 1635, but Junius learned about the plans and had the leaders arrested before anything could happen, historian Tonio Andrade writes in How Taiwan Became Chinese.

“Whenever Mattau flouted company authority, people in the other villages also grew restive,” Andrade writes.

The people of Sincan were already at war with the Mattau, having captured a chief and beheading one of their warriors. With their allies turning against them, and their people dying due to smallpox, the villagers were about to flee when the Dutch-Sincan troops entered the village. Nobody offered resistance. Twenty-six residents were killed and the village was burned to the ground.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A week later, the two sides signed the seven-article Mattau Agreement, in which the villagers, among other concessions, relinquished all sovereignty to the Dutch and pledged to never attack them or the Han settlers again. It is considered Taiwan’s earliest recorded international treaty.

On Dec. 2, 1635, representatives from Mattau offered betel nut and coconut saplings to the Dutch governor as a “symbol that the sovereignty of their country had now been given to the [United Provinces],” Junius writes in the report. In turn, the Dutch chose four Mattau leaders as “spokesmen,” giving them orange flags, black velvet robes and rattan staves with silver heads bearing the company’s insignia, thus “marking both their authority and their subjection to the company,” Andrade writes

HISTORIC RIVALS

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The closest major communities to the Dutch when they first arrived were Sincan, Soulang, Baccluan and Mattau. These villages often fought each other in shifting alliances, and they were eager at first to ally with the Dutch against their local rivals.

Before the Dutch even settled in Taiwan, Mattau warriors attacked an expeditionary force sent from Penghu in 1623 to build fortifications near today’s Anping District (安平) in Tainan. They were upset that the Dutch allied with the Sincan, and harassed them over the next decade in an increasingly calculated effort to sabotage their operations and rid them from the island. Besides raiding settlements and killing soldiers, they also uprooted crops and destroyed buildings, including VOC facilities.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

VOC headquarters, however, were reluctant to send reinforcements, as the company did not think Taiwan was worth investing in, with surrounding trade routes affected by Chinese pirates and Japanese merchants.

“Consequently, we were regarded with very much contempt by all the people, especially by those of Mattau, who often showed how very little they were afraid of us, venturing not only to ill-treat the Chinese provided by our licenses, but even tearing up Your Excellency’s passports and treating them with contempt,” Junius writes.

The villages continued to fight with each other, with the Dutch often being dragged into the conflict. When Mattau raided Sincan in 1625, the Dutch were obligated to help Sincan as their allies. They persuaded the aggressors to return the looted goods and pay an indemnity of two pigs.

NO AUTHORITY

But the following year, Sincan attacked Mattau and its ally Baccluan, then requested that the Dutch protect it from retribution, Andrade writes.

The Dutch clashed directly with Mattau, and using their guns, forced them and Baccluan to pay an indemnity to Sincan. However, they could not maintain authority over the two villages, which continued to harass Sincan, and the latter became entirely dependent on Dutch protection.

“Without this protection, [Sincan] would not stand for even a month,” wrote missionary George Candidus in a VOC report.

That summer, Mattau warriors ambushed a Dutch contingent, who had entered the village looking for Chinese pirates. The Mattau were hospitable at first, but they struck shortly after the Dutch left, killing 61 of the 63 soldiers. Afterward, they ransacked Sincan along with their ally Soulang, which had generally maintained good relations with the Dutch. Perhaps emboldened by the events, the Soulang killed a Dutch official living in their village.

Afterwards, Mattau held a party, boasting “that [the Dutch] fear them and dare do nothing in revenge,” Andrade writes.

The Dutch needed to do something. Not confident in their ability to take on Mattau, they instead attacked their Bacclun allies “by fire and sword,” Janius writes. Baccluan sued for peace, and Mattau also reached a nine-month ceasefire with the VOC.

MATTAU’S DOWNFALL

By 1634, things were looking bad for Mattau. Relations had soured with its strongest ally, Soulang, over the alleged Soulang killing of a resident of Tirosen (a Mattau ally). Worried about Mattau retribution, Soulang teamed up with Sincan and turned against Mattau.

Mattau could fend off a joint attack, but they were worried that the Dutch would join the fray. The Dutch watched the situation closely and tried to play up the tensions between the groups.

With the Chinese pirates under control and trade with Japan flowing again, Batavia sent the long sought-after troops to Fort Zeelandia, also in today’s Tainan. Around this time, the warring villages decided that they should focus on driving out the Dutch — but it was too late.

When the long-awaited revenge expedition set out, Mattau was floundering. Not only had Tirosen turned on them, they had lost hundreds of warriors to smallpox, which they had no immunity against.

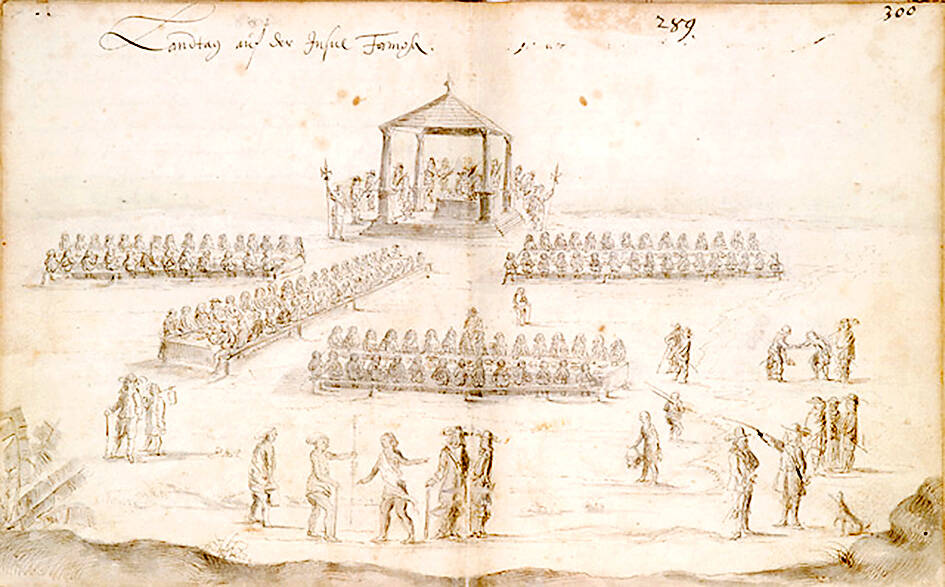

The Dutch publicly signed a peace treaty with Mattau, since “the event ought, in order to have more weight, to occur in the presence of all the villages in the area,” writes governor Hans Putmans to Junius. Representatives from other villages watched as the Mattau officially surrendered and signed the treaty.

The Dutch rode the momentum and burned down the village of Taccariang, whose warriors had previously raided Sincan and VOC property. They then marched into Soulang, imprisoning those involved in the events of 1629 and torching their houses.

A huge ceremony was held in February 1636, where 28 villages pledged their allegiance to the VOC. Junius writes that the purpose was “to give the entry of the villages into Dutch sovereignty a more official status, and to bind these villages, which were usually at war with each other, to the ... company and also to each other.”

“From this you will see the favorable results of the war, and how well it has been that Mattau and Taccariang were burnt for the evil committed against us,” Junius writes to the VOC after a later ceremony where their “united villages” gained 29 more members.

“How great has been your acquisition of territory! How wide a door has been opened to us for the conversion of the heathen!”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)