Oct. 24 to Oct. 30

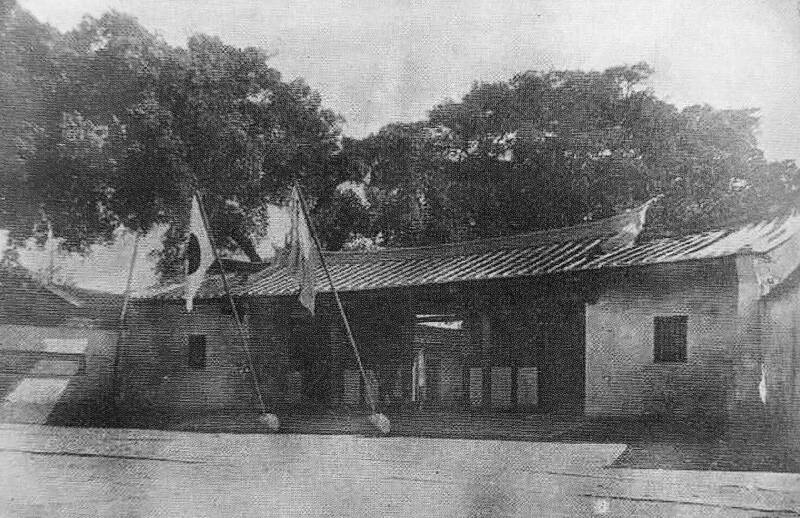

Hsueh Yung-tung’s (薛永棟) “eight years of vicissitude” (八年滄桑) officially began at dawn on Oct. 26, 1937 when the Japanese attacked Kinmen.

Having blockaded the island on Sept. 3, the Japanese limited their activity to scouting and surveying missions until Oct. 23, when larger warships entered the harbor. Things quickly escalated and the invaders overran the island, facing little resistance over the next few days while villagers fled in scores, many heading to China or Southeast Asia. Japanese military records show that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops stationed there fled immediately, and only one person — a member of the local self-defense force — died in the process.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The occupation took place just three months after the Japanese initiated the Second Sino-Japanese War, putting them a step closer to their true goal — the vital port of Xiamen.

Hsueh had made his fortune in the Philippines, and returned home in old age only to fall upon this misfortune. More than half of the 571 residents of his Zhushan Village (珠山) had fled, including all of his family besides his wife and three maids. Although his life was not in danger, the sudden desolation was haunting.

Hsueh kept a log of life under what he called the “puppet government” (偽政府) until his death in 1943, upon which an unknown source took over. Its entire contents were published after the end of the war in the Hsueh family’s newsletter Shining (顯影).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

By contrast to Hsueh’s somber tone, local officials in the administrative office set up by the Japanese wrote of a productive, harmonious society that thrived after being freed from the clutches of the evil KMT. The invaluable book, Blazing Sun Shining (烈日顯影) by Lin Cheng-chen (林正珍), provides original texts from both sides, making for a fascinating juxtaposition.

LIFE UNDER OCCUPATION

The invasion force disbanded on Oct. 29, leaving 250 men stationed on the island. On Nov. 28, the White Hawk Defense Force’s first division took over and set up headquarters in today’s Jincheng (金城) area. Meanwhile, the KMT moved the Kinmen County Government office to Dadeng Island (大嶝島) to the north, which is now part of the city of Xiamen.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In May 1938, the Japanese used Kinmen as a springboard and successfully seized Xiamen. With this event, the Japanese controlled both sides of the strategic Taiwan Strait.

Unlike Taiwan, Kinmen was not a colony; it became a special municipality of occupied Xiamen with its own administrative office and police force. A state-run company was set up to produce salt, conduct trade as well as handle transportation, banking and other essential industries.

By 1939, the population had rebounded somewhat, as many who fled to Xiamen returned home.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Lin writes that besides two KMT attempts to reclaim the island and several guerilla attacks by Kinmen exiles based in Fujian Province, there was little conflict with the occupying troops.

“Weddings, funerals, celebrations, religious activities as well as folk activities and entertainment did not seem affected by the occupation,” she writes.

However, with remittances from the many islanders living abroad cut off, Hsueh writes that there was often not enough to eat, especially after a poor harvest in 1938. Thieves often made off with crops and other household objects at night, further causing hardship.

Most accounts of Japanese mistreatment toward locals came in the form of forced labor which, in addition to various construction projects and transportation tasks, included planting opium for the monopoly bureau in Taiwan. The drug was also sold in Kinmen, and many residents became addicts.

As Japan lost ground near the end of World War II, the army also seized raw material and resources from the people. Allied bombings increased, with one instance on Aug. 30, 1944 killing 19 islanders, including two of Hsueh’s relatives.

In June 1945, about 500 men were forcibly conscripted with their mules and sent to China. Only about half of them returned home, and the ones who did were branded as traitors by the KMT.

SHINING PARADISE?

According to Japanese reports, however, Kinmen residents were overjoyed at their arrival. A Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) report from November 1937 states that the islanders were grateful to the Japanese for treating them during a malaria epidemic, and requested that the Japanese establish official rule as soon as possible. It also alleged that those who escaped to China were all slaughtered by KMT troops.

“Due to Japanese occupation, the islanders are finally free of the harsh and exploitative rule of the Chinese government,” another article states. “Under the protection of the disciplined but kind Japanese troops, they can fish and farm without worry. The Japanese doctors also carefully treated local diseases … and tended to the patients. It’s as if the sun finally shines on the islanders again.”

The reports all follow the same tone, with one describing how the local self-defense association petitioned the Japanese troops to “promise never to return Kinmen to China.”

“Kinmen is a true paradise,” a headline read, highlighting how the islanders were proactively trying to overturn the anti-Japanese sentiment of their kinsfolk living abroad. These sort of reports continued until around 1942.

The local government, mostly composed of pro-Japanese locals, Taiwanese or Chinese from Japanese territory, fell under Japan’s East Asia Development Board. Administration chief Wang Ting-chih (王廷植) thanked Japan for saving the island from the clutches of KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), whose collusion with the Chinese Communist Party to fight the Japanese would spell China’s doom.

“Friendship between China and Japan is the only way to maintain eternal peace in East Asia,” Wang said. “I want to remind the people to release themselves from the bewitchment of Chiang’s regime, and lean toward peace!”

The bloodiest incident during these eight years involved two Taiwanese officials, who were kidnapped in 1943 by anti-Japanese agents at the salt fields of Xiyuan (西園) and taken to China, where they were executed. The Japanese arrested about 300 young men in Xiyuan they suspected of abetting the agents and tortured many of them to death. Four were convicted and executed on the beach. A monument in Xiyuan remembers this tragedy, as well as the many anti-Japanese Kinmen exiles who died on mission.

The Japanese surrendered to the Allies on Aug. 15, 1945. The Taiwanese in Kinmen were subject to attacks by locals afterward, and sought protection in the Japanese army headquarters. After a two-month period without a government, new county commissioner Yeh Wei-tsou (葉維奏) landed under heavy military protection on Oct. 3, 1945.

A massive, island-wide celebration was held on Oct. 10, drawing this chapter of history to a close.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the