Long before Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite triumphed at the Oscars and Squid Game circled the globe, Park Chan-wook was astonishing worldwide audiences with his sumptuously stylistic, outrageously violent and devilishly elaborate vision of Korean cinema.

His latest, Decision to Leave, is in some ways more restrained than Park’s previous films. It lacks the brutal violence of Oldboy (2003) or the eroticism of The Handmaiden (2016). But it might be his most devastating.

The film, which is South Korea’s Oscar submission, is a twisty noir entwined with a love story. Park Hae-il plays a Busan police detective who becomes infatuated with a murder subject (Tang Wei, 湯唯). Their evolving relationship plays out as an investigation. Intricate and mischievous, Decision to Leave is yet another genre tapestry for the masterful Park to make an elegant plaything of. At the Cannes Film Festival in May, it won him best director.

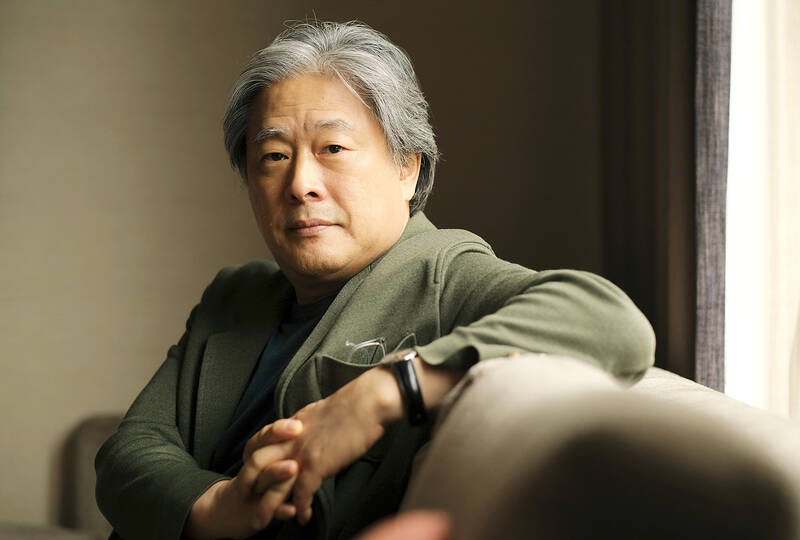

Photo: AP

Ahead of the film’s release in theaters today, Park met a reporter during a break at the New York Film Festival. Through an interpreter, he discussed making Decision to Leave (one of the biggest box-office hits this year in South Korea), his role in expanding Korean cinema’s footprint and why — regardless of bloody hammers or octopuses eaten whole — love has always really been his main subject.

AP: The room you write in has been compared to the room that traps the protagonist of Oldboy. Is that true?

PARK: (Laughs) When we designed the house, we made a room specifically for me to write in. It’s a small room with just a table and desk and it almost feels like you’re going to suffocate inside. But I don’t just write in that room. I really write anywhere. I write in offices, cafes, hotels and on the plane.

Photo: AP

AP: You live a relatively quiet life in between films, don’t you?

PARK: My house is in a small town in a remote area outside Seoul. My production company is also on the outskirts of Seoul. So I’m almost like someone who works in a company going back and forth between my office and my house.

AP: What was on your mind when you and your co-writer, Jeong Seo-kyeong, wrote Decision to Leave?

Photo: AP

PARK: At that time, I was working on post-production for Little Drummer Girl, and I had to direct the entire six-episode series myself. It took a lot of time and was also very physically demanding. I became home sick. Of course my wife was with me, but still.

During that post-production phase, my co-writer went on a family trip to London and met me twice at a cafe. We had general conversations about what my next work should be. The two core principles that we started off with were: I wanted the film to be a Korean film and I wanted it to play in theaters.

The next thing was that I wanted it to be a police film. I think it’s because at the time I was reading the Martin Beck series. I was very much influenced by that. I wanted to start off from a very familiar setting: A detective assigned to a murder mystery. And I wanted to make a romance.

AP: Your film suggests that everyone’s guilty in love, but suspicion will kill it.

PARK: That’s a nice way to express it. When you’re in love, you’re naturally curious about the other person. You want to know more about them. Throughout this process of love, there’s always that sense of doubt that makes you want to dig in deeper. When that takes a dramatic form, it might even turn into stalking their social media or looking at the phone or asking questions to test if they’re lying. A lot of people do such things or have the desires to do such things. When you reach that point of doubt and suspense, I think it really becomes similar to a detective’s investigation.

AP: Love might not be what some immediately think of as the principle theme of your films. Why do you think you keep returning to love stories?

PARK: All of my films are basically about people in love. But each of these works in my filmography have their own genre elements, like thriller or horror. I think that comes off too strongly and makes people forget it’s about love. An artist’s occupation is naturally to explore what mankind really is, and I believe the best subject to explore the characteristics of mankind through is love. But even as an entertainer, love is the best subject. Love has thrill, it has mystery, it has comedy, it touches you and it horrifies you.

AP: Your movie is often funny, even farcical, but ends, unforgettably, in tragedy. How did you see that tonal arc working?

PARK: There are some tragedies where it’s just a progression of sad events happening. But I guess there’s also tragedy that comes from a movie that doesn’t seem that way. That contrast brings out the tragedy even more. There’s something very farcical about their situation. There’s farce that comes from sympathy. Without laughter, I feel like I’m forcing an emotion on the audience. As if I’m telling them: “You’re sad, right?” “You’re horrified, right?” There’s a sense of totality that comes from humor that fills up all the missing holes.

AP: How technology shapes the lives of men and women has also been a hallmark of your films. Why did you crowd Decision to Leave with phones, text messages and translation apps?

PARK: I wanted this movie to feel very classical and have these mythical elements. If you consider the last scene, it really resembles Orpheus. But I didn’t want this to be the kind of classical film with handwritten letters. If I wanted to do that, I could have put it in a setting where there were no phones. A lot of directors feel the desire to do this. Instead, I chose to actively incorporate modern technology, even more than you see in shows about teenagers like Euphoria. Making that decision was a significant moment for me.

AP: Are you proud of your role in spreading Korean film and pop culture?

PARK: If I had set that goal to spread the love of Korean cinema and worked hard towards it, I would have some pride in doing so. But the truth is, it just kind of happened that way. It’s merely a result of me trying to have fun making my works and allowing the audience to have fun watching my works. I’m never self-conscious of non-Korean audiences or foreign audiences when I’m making my film. It’s more that I make my film with the intention of Korean audiences of the future to enjoy them. Fifty or 100 years later, I want them to enjoy it just as much as contemporary audiences.

Late last month Philippines Foreign Affairs Secretary Theresa Lazaro told the Philippine Senate that the nation has sufficient funds to evacuate the nearly 170,000 Filipino residents in Taiwan, 84 percent of whom are migrant workers, in the event of war. Agencies have been exploring evacuation scenarios since early this year, she said. She also observed that since the Philippines has only limited ships, the government is consulting security agencies for alternatives. Filipinos are a distant third in overall migrant worker population. Indonesia has over 248,000 workers, followed by roughly 240,000 Vietnamese. It should be noted that there are another 170,000

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the

“Far from being a rock or island … it turns out that the best metaphor to describe the human body is ‘sponge.’ We’re permeable,” write Rick Smith and Bruce Lourie in their book Slow Death By Rubber Duck: The Secret Danger of Everyday Things. While the permeability of our cells is key to being alive, it also means we absorb more potentially harmful substances than we realize. Studies have found a number of chemical residues in human breast milk, urine and water systems. Many of them are endocrine disruptors, which can interfere with the body’s natural hormones. “They can mimic, block

Pratas Island, or Dongsha (東沙群島) had lain off the southern coast of China for thousands of years with no one claiming it until 1908, when a Japanese merchant set up a facility there to harvest guano. The Americans, then overlords of the Philippines, disturbed to learn of Japanese expansion so close to their colony, alerted the Manchu (Qing) government. That same year the British government asked the Manchus who owned the island, which prompted the Manchu government to make a claim, according to South China Sea expert Bill Hayton. In 1909 the government of Guangdong finally got around to sending