Zoila Lecarnaque Saavedra sealed her fate when she agreed to transport a package from Peru to Hong Kong — a decision that landed her more than eight years in prison.

A quarter of Hong Kong’s prisoners are women, a record-high percentage skewed by impoverished foreign drug mules who are often duped or coerced.

Awaiting deportation after her release, Lecarnaque Saavedra sat on a bunk bed in a cramped hostel and described how she lost her gamble for quick money.

Photo: AFP

It was 2013 and she was broke. Her husband, the main breadwinner for her family in Peru’s capital Lima, had recently left and she needed eye surgery.

Word got around the neighborhood and she said she was soon approached by a woman who offered her a deal: fly to Hong Kong to pick up tax-free electronics that could be sold for a profit on return, and be paid US$2,000.

“They find people who are in a precarious economic situation,” Lecarnaque Saavedra said. “They look for them and in this case it was me.”

Photo: AFP

A diminutive figure with a face lined by hardship, 60-year-old Lecarnaque Saavedra said she wanted to warn others who might be tempted by such deals.

She lost composure when recounting the moment customs officers pulled her aside and it dawned on her she would not be seeing her daughter and mother for many years.

“I reflected on the damage I caused to my family, to my children, to my mother, because they were the ones who felt worse than me and that hurts me,” she said, her eyes filling with tears.

She described how officers found two jackets inside her suitcase that had been filled with condoms containing about 500 grams of cocaine in liquid form. In the hopes of receiving a lighter sentence, Lecarnaque Saavedra pleaded guilty, though she maintains she did not know about the cocaine and was never paid.

“The bosses are free, they have not been arrested and I don’t know why,” she said.

‘COERCION COMES IN MANY FORMS’

That story is all too familiar in Hong Kong women’s prisons.

Activists, prison volunteers, lawyers and women in jai said foreign drug mules make up a major chunk of those in female prison wings.

Hong Kong Correctional Services said 37 percent of foreign inmates were female but declined to comment on the reasons for this. With a thriving port and airport, Hong Kong has long been a global hub for trade both legitimate and criminal.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, its airport was one of the world’s busiest and best-connected.

Drug syndicates favor using women as mules, believing they are less likely to draw attention from authorities.

Official statistics show that a quarter of the 8,434 people serving time in Hong Kong last year were women — the highest rate globally, according to the World Prison Brief. Hong Kong dwarfs second-place Qatar, another global transport hub, where 15 percent of people in prison are women. Only 16 other countries or territories have proportions above 10 percent.

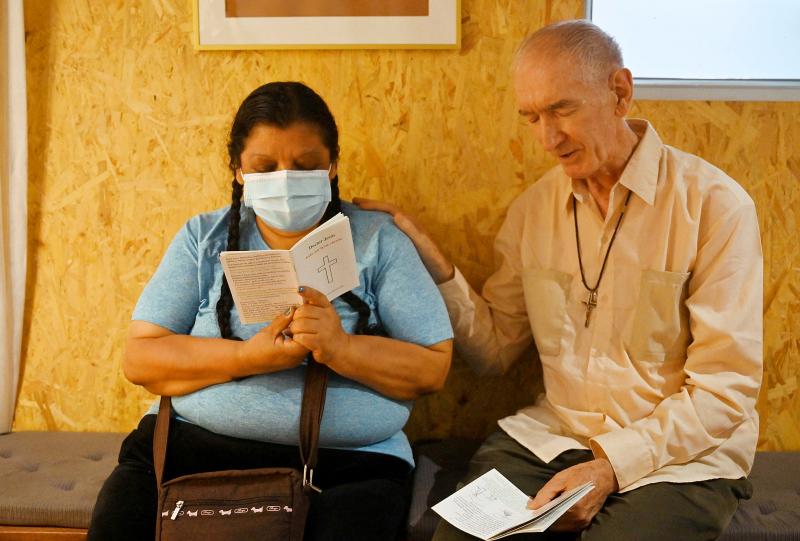

Father John Wotherspoon, a Catholic prison chaplain who has spent decades working with convicted drug smugglers, said the vast majority of female mules were vulnerable foreigners.

“Coercion is a big problem and it can come in many forms, economic, physical, emotional,” he said in his office in a crowded Hong Kong neighborhood known for its red-light businesses.

Wotherspoon, a bundle of energy at 75 years old, has traveled repeatedly to Latin America to try and help families of those arrested — even confronting traffickers at times. He attends many of the drug trials that fill the daily schedule at Hong Kong’s High Court, raises donations for the convicted and helps maintain a Web site that names some of the characters he thinks should be behind bars — collected in part by testimony from those in jail.

“The big problem is the masterminds, the big fish I call them, don’t get much of a mention,” he said.

PERPETRATOR OR VICTIM?

Drug mules are easy pickings for police and prosecutors in Hong Kong, where an early guilty plea usually results in prison time being reduced by a third.

Fighting a conviction is risky, given the city’s harsh drug rules. Sentencing guidelines begin at 20 years for more than 600 grams of cocaine.

In 2016, Venezuelan national Caterina got 25 years in prison after failing to persuade a jury she was coerced into being a mule.

She alleged she was kidnapped by a gang in Brazil after answering a fake job advertisement. She said she was repeatedly raped, and her family threatened, until she agreed to fly to Hong Kong.

“They treated me like trash, I was afraid they were going to kill me,” 36-year-old Caterina, who asked not to give her real name to protect her family, said from prison in Hong Kong.

Pregnant before she was kidnapped, Caterina gave birth to a baby boy in prison and her subsequent appeal failed.

“I have been working for many years with vulnerable people, but this is one case that hangs over me,” said Patricia Ho, a lawyer who helped with Caterina’s appeal.

“What I cannot shake out of my mind is that I would have done exactly the same thing as she did.”

Ho said one of the big issues defense teams encountered was that, although Hong Kong recognizes human trafficking is a problem, there is no specific law outlawing it. That means prosecutors, judges and juries rarely take into account whether a mule is a trafficking victim.

“Through force or coercion — whatever words you want to throw in there — she was forced to commit a crime. That to me all fits squarely within the definition of human trafficking,” Ho said.

SEPARATING FAMILIES

Some mules know what they might be carrying but feel compelled to take the risk because of their circumstances. At first glance, Marcia Sousa’s Facebook profile looks like any other young Brazilian’s: filled with selfies showing off new braids and photos of parties with friends at the beach. But four years ago, the updates abruptly stopped.

Shortly after that, Sousa was arrested at Hong Kong’s airport carrying just over 600 grams of liquid cocaine in her bra.

She later told the court that she came from a poor family from northern Brazil, had a mother who needed kidney dialysis and had fallen pregnant with a man who abandoned her.

She gave birth in prison while awaiting trial. At her sentencing, Judge Audrey Campbell-Moffat praised the 25-year-old for a host of mitigating circumstances, including pleading guilty early, cooperating with police and prison reports that she was a model mother to her son.

“There is little more you could possibly have done to show your genuine remorse,” Campbell-Moffat said as she reduced her sentence from the recommended 20 years to 10 years and six months. A few weeks later, AFP met Sousa, who asked to use a pseudonym to protect her family from any potential repercussions.

“I tried my best to tell the judge to forgive me. I know I did something criminal, but it was for my son,” she said through a prison phone, dressed in a beige uniform and shielded by thick plexiglass.

“I was angry. But afterwards, I realized she was right to give me the sentence, she was balanced.”

For the first few years of her son’s life, Sousa was allowed to take care of him in prison. But as his third birthday approached, he was taken into care until he can be sent to Sousa’s family in Brazil.

“He cried a lot and didn’t eat,” Sousa said of those first few weeks after the separation.

All her thoughts, she said, revolved around being reunited with him.

“I’m thinking of the future, taking care of my son,” she said.

But that future was pushed further into the horizon when prosecutors successfully appealed her sentence, arguing it was too lenient, with Sousa this month given a further two years.

MULE SURGE?

As the pandemic hammered air travel, the number of drug mules worldwide plunged.

Traffickers shifted to post and courier shipments, with big deliveries made via air freight and shipping containers.

But as the pandemic eases, drug mules will almost inevitably return to the skies.

That means more women like Zoila will be lured into a trade fueled by smugglers and consumers that care little about whether they succeed.

Last month, Zoila was deported from Hong Kong, a day she had been dreaming of for years.

She beamed as she pushed her baggage cart through the arrivals hall at Lima’s airport and headed to her family home a short drive away.

“I cried because it has been almost nine years, now I’m going home,” she said. “My mother, my brothers and sisters, my children are waiting for me. The whole family is waiting for me at home.”

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled