Aug. 1 to Aug. 7

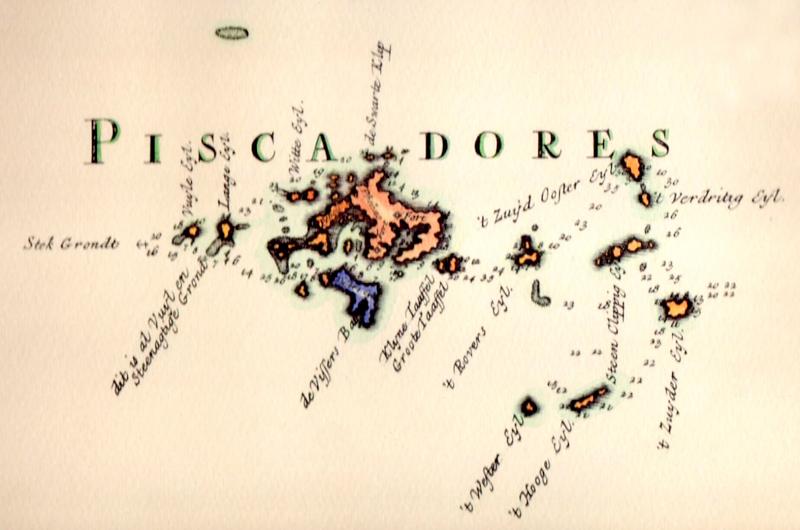

Admiral Cornelius Reijersen stubbornly held out at Penghu’s Makung harbor (馬公) for nearly two years, refusing the Ming Dynasty’s repeated requests for his fleet to depart for Taiwan.

Instead, the Dutch fleet plundered Chinese merchant ships, captured sailors and terrorized the coast of Fujian for months, hoping to force the Ming to open up trade with them.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

To the Ming, Penghu was too close to home; they knew of the Dutch’s military strength and they were also worried that the archipelago would become a pirate haven with ships smuggling goods there to avoid paying taxes. They did not consider Taiwan to be under their jurisdiction, and had no problem with them relocating there.

But Reijersen had already surveyed the west coast of Taiwan when they first arrived in July 1622, and could not find a harbor deep enough for the fleet to dock.

More than a year of negotiations and clashes later, the Ming had had enough. In August 1624, a fleet of 200 ships and 10,000 troops surrounded Makung and cut off its supply routes. They didn’t even want the Dutch in Taiwan anymore and they wanted to force them back to their headquarters in Batavia (present day Jakarta).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

At this time, the influential smuggler Li Dan (李旦), known to Europeans as “Captain China,” stepped in and brokered a truce between the two sides. The Dutch finally packed up and set sail for Taiovan (today’s Tainan area), and the rest is history.

FIRST OCCUPATION

Dutch interest in Asia began in 1602 with the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). They immediately clashed with the Portuguese, who had been active in the area for nearly a century. In 1603, the Dutch captured the Portuguese merchant ship Santa Catarina in the Malacca Strait, which was loaded with Chinese goods such as silk and porcelain. They made a fortune auctioning off the items in Europe, and this event sparked their determination to open up trade with the Ming Dynasty.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In 1604, vice admiral Wybrand van Warwijck set sail for Macau in an attempt to drive out the Portuguese. However, a typhoon forced his fleet to take shelter in Penghu, where he began building a permanent base. He then contacted the Ming authorities in Fujian with the hope of negotiating trade privileges, but the powerful eunuch Kao Tsai (高寀) told him he had to pay an exorbitant fee to reach the emperor.

Many sources state that van Warwijck rejected the offer, but Yang Tu (楊渡) writes in the new book, Dutch Ships in Penghu Bay (澎湖灣的荷蘭船) that he paid part of it and began privately trading with Fujian merchants while he waited for news from Kao.

Meanwhile, the Ming officials in Fujian were eager to get rid of the Dutch. After much debate, General Shen Yourong (沈有容) set out for Penghu with 50 warships and 3,000 troops. He did not want conflict; he hoped that his vastly superior numbers were enough.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Shen was courteous and released the interpreter they captured earlier as a sign of goodwill. However, he stopped all ships from leaving the harbor and had troops patrol the coast. Shen was awed by the size of the Dutch warships and their mighty cannons, but he remained firm, as there were only three of them at Penghu.

Fortunately for van Warwijck, the man who was supposed to deliver the money to Kao had not left Penghu yet, and he got his cash back, Yang writes. However, he still refused to leave, and a month passed before the he and Shen met at Makung’s Tianhou Temple (天后宮). Shen told him that more troops were coming from Fujian, and gave him one last chance to leave peacefully. Van Warwijck obliged.

RAIDING DUTCHMEN

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

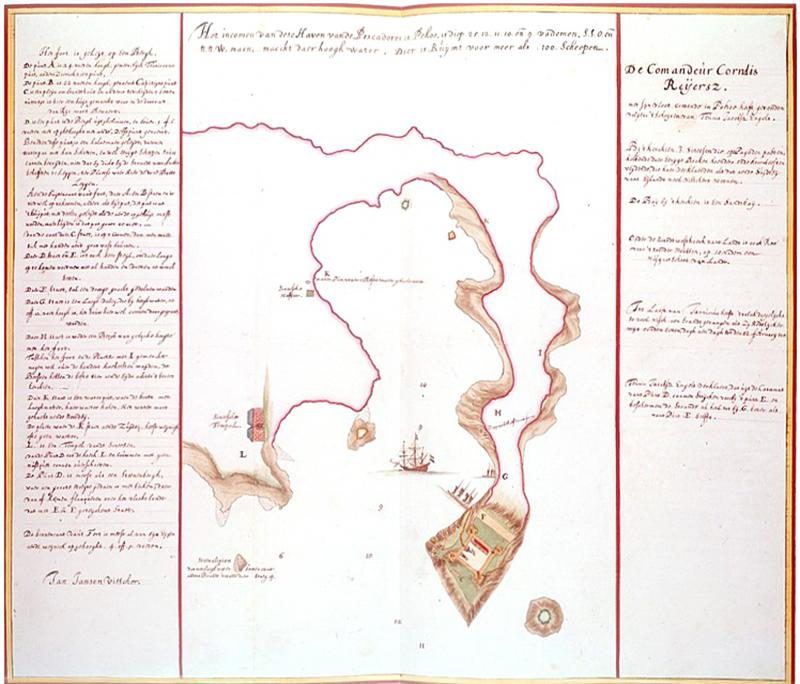

The Dutch continued to attempt to dislodge the Portuguese and get the Ming Dynasty to trade with them, to no avail. After launching an unsuccessful attack on Macau in 1622, admiral Cornelius Reijersen retreated to Penghu. They did consider Taiwan, but the Dutch traversed the west coast and could not find a harbor deep enough for their ships. They returned to Penghu and started building fortifications around Makung harbor in August 1622.

Alarmed, a Fujian official arrived and told Reijersen that the Ming were willing to trade with the Dutch, they just didn’t want them in Penghu. Reijersen writes in a letter to the VOC that the official promised to have a guide bring them to Tamsui in northern Taiwan, a place outside of Ming jurisdiction, where there was abundant gold and food, as well as a large harbor for their ships. They could freely trade with the Ming there.

This was too good to be true, and Reijersen insisted on staying in Penghu, threatening to capture any Chinese ship that passed through the nearby waters. They also raided the Chinese coast, attacking the port of Zhangzhou on Oct. 18, 1622, burning up to 80 boats and taking dozens of prisoners. They also plundered local villages, seizing livestock and supplies.

James Davidson writes in The Island of Formosa: Past and Present that these captured sailors and locals were forced to help build the forts. The conditions were so harsh that 1,300 of the 1,500 workers died, mostly from starvation. The Dutch argued that their people were treated just as badly by the Ming.

“Furthermore, batches of natives were sent to Batavia to be sold as slaves, and the awful fact is recorded that less than half of them reached their destination alive,” Davidson writes. “Several villages on the coast were ravaged, and many cruelties committed, actions which were characterized by [historian Valentyn] as a disgrace to Christianity.”

The actions of the Dutch caused all merchant ships to cease visiting Penghu, and they began running low on food and supplies as the land was poor and sparsely populated. The northerly winds started howling as winter fell, and the men were falling ill from disease. The Dutch continued their plundering to survive, but Reijersen knew this was not a long term solution. Meanwhile, he sent an expedition to Taiovan to build a fortress and trade with smugglers there.

TAIWAN BOUND

Fujian officials tried to keep the news under wrap, but the emperor finally learned of the Dutch aggression and immediately installed Nan Ju-yi (南居益) as the new governor in August 1823. Nan asked the Dutch to leave Penghu and Taiwan and release the captives, while Reijersen said he had no authority to leave and wanted the Ming to stop trading with the Spanish in Manila. With talks making little progress, the two sides prepared for war.

After a few months of clashes, the desperate Reijersen finally contacted Batavia for permission to leave, and tendered his resignation. Martinus Sonck arrived in Penghu to replace him on Aug. 1, 1624, by which time 150 warships carrying 4,000 Ming soldiers were readying an attack. This number continued to grow over the following weeks. Sonck was instructed to avoid fighting due to VOC’s financial difficulties, but the Ming were tired of negotiating.

At this time, the influential smuggler Lee stepped in. Lee persuaded the two sides to agree on the Dutch peacefully leaving Penghu and occupying Taiovan, where they could freely trade with the Ming. This changed Taiwan’s fate forever, with Sonck becoming its first Dutch governor.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them